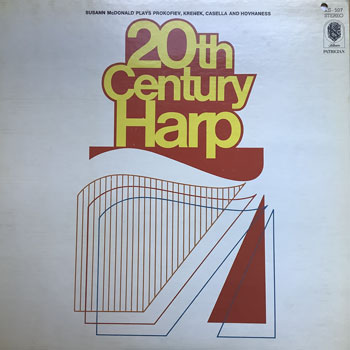

20th Century Harp:

A Vintage LP as Window into a Better World

by Kurt Wildermuth

(June 2023)

What's a tougher sell than, say, twentieth-century flute music? It just might be twentieth-century harp music. So after celebrating the 1975 album Twentieth-Century Flute Music, I couldn't resist a thrift-shop copy of the 1972 album 20th Century Harp. These records have no connection other than their early-'70s vintage and their lack of commercial potential. But I am here to report that like the flute, the harp has far more expressive potential than most of us might give it credit for.

It helps that the harpist on this album is Susann McDonald. Wikipedia tells me that McDonald, born in 1935, has enjoyed a long, accolade-laden career as performer, teacher, academic, and recording artist. Beginning with her first album, Récital de Harpe (1968), McDonald recorded both modern compositions and older ones. For her fourth album, 20th Century Harp, she assembled the fully modern program announced in the title.

The album was released by Klavier Records, an instrumental-music label founded by Harold L. Powell in 1970. Produced by Powell, 20th Century Harp was the twelfth of the nearly 300 recordings the label released before being sold off in 2020. Like many or even most of Klavier's catalog, 20th Century Harp has not been reissued.

It is an exquisitely selected and sequenced collection of accessible yet challenging compositions written for the harp, and as a whole it makes a strong case for the harp's sonic range and interestingness. Our jaded postmodern ears might take the instrument's beauty for granted or dismiss it as kitsch. The direly cliched view of the harp is as angelic accompaniment, the celestial soundtrack of heaven's gate welcoming the good.

Adventurous listeners should push past that dead image. For example, fans of orchestral music may be familiar with the sight of a harpist onstage, lending some of the instrument's chiming to an instrumental mix. Fans of jazz may be familiar with the flights of harpist Alice Coltrane, who reached for transcendence in ensembles with her husband, the saxophonist John; as a solo artist; and in collaboration with fellow searchers. Fans of indie rock may be familiar with the work of Joanna Newsom, a singer-songwriter who backs her acquired-taste vocals with her solo or sparely accompanied harp playing. On 20th Century Harp, however, Susann McDonald's harp accompanies nothing but the spaces between notes.

And what notes, what spaces! 20th Century Harp was so well recorded and this pressing so well manufactured that an audiophile might use the album to test the fidelity and warmth of stereo equipment. In pristine condition, simply as an artifact of analog technology, this LP is a work of art.

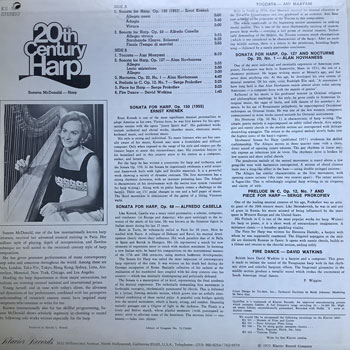

McDonald's playing, meanwhile, seems purely at the service of compositions that may have represented twentieth-century aesthetics but retain all freshness in the twenty-first century. For specifics on the pieces and composers, I turn again to Wikipedia, plus the album's liner notes (by one P. Wiggins).

Exemplifying this album's perfect programming, the first side consists of two sonatas from different times and periods that nonetheless flow perfectly into an illustration of the harp's versatility. The opening piece is the Austrian-American composer Ernst Krenek's nine-minute Sonata for Harp, Op. 150 (1955). By 1955, Krenek was employing such stringent and astringent materials as serialism, twelve-tone, and electronics, but this sonata is so much more accessible than those materials would suggest. It combines high plucked notes with low ones that sound like piano and carry a somewhat sinister undertone. Fast runs in the first part, Allegro assai, lead to meditative ones in the second, Adagio, then a lighthearted Vivace. Throughout, the deliberateness feels like a mind at work, drawing on the heart, using this unfamiliar sonic palette to explore places otherwise inaccessible.

The Italian pianist and composer Alfredo Casella was, fascinatingly, a modernist, a neoclassicist, and in 1927-29 the conductor of the Boston Pops. Wiggins calls him "the foremost figure in Italian music during his last 25 years." Casella's sixteen-and-a-half-minute Sonata for Harp, Op. 68, written in 1943 on his deathbed (!), "was called the most important of contemporary harp repertory of this time." The first movement, Allegro vivace, continues the combination of intellect and feeling in Krenek's sonata--neither discordant nor saccharine, which must be a supreme achievement in a modernist take on the harp. The second movement, Sarabande (Grave, Solenne), progresses from gentle to gently intense to pensive, as though the head is bowed in prayer. The finale, Tempo di marcia, exhibits a surprisingly rousing physicality before ending on a sweet, high, thoughtful, not overtly triumphant note. I'm guessing that whereas Krenek's sonata is grounded in the secular, Casella's ventures at least partly into the spiritual.

Side Two opens with the six-minute Toccata, composed by the Israeli composer, conductor, and architect Ami Maayani in 1961. Maayani created many pieces for and including the harp, and Wiggins considers this example "one of the most rhythmically exciting of contemporary harp works--covering a full prism of musical nuances." Here the harp has the resonance of bells, the richness of a guitar, as McDonald works the strings in successions of plucks or quick strums, often returning to a simple repeating pattern. As in Krenek's sonata, where the harp could be accompanying itself on piano, this piece creates the illusion of instrumental interplay, then wraps up with the equivalent of vanishing.

Next up are Alan Hovhaness's nine-and-a-half-minute Sonata for Harp, Op. 127 (written in 1954) and four-and-a-half-minute Nocturne, Op. 20, No. 1 (written in 1937, revised in 1961). Hovhaness, an American avant-gardist, anticipates the work of minimalists, but fans of instrumental rock may be reminded of Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells (1973), particularly its best-known passage, which figured prominently in the soundtrack of The Exorcist (also 1973). Indeed, as in so many compositions here, an otherworldly somberness inhabits the surface beauty and delicacy. The Allegro displays an expressive directness and rhythmic emphasis. The Lento misterioso presents a somber take on what feels like the same sonic space; it could be an X-ray of the opening Allegro's bones. The third part, a second Allegro, returns to the drive of the opening but with added vigor. Nocturne conveys the tranquility of a particular nighttime, a night not of partying but of reflecting. This potential lullaby is characterized by long, majestic strokes.

Of the composers named here, the one most likely to ring bells for most people is Serge Prokofiev, a Russian. Prokofiev's Prelude in C, Op. 12, No. 7, and Piece for Harp are each two and a half minutes long. The first feels like what most people think of as classical music, with a regal air and perhaps nods to Mozart. The second begins with a note that could be a continuation of the prelude, but it proves to be considerably slower and eerier, its tones stretched out perhaps as far as a harp's can be.

The album closes with Fire Dance, by the English-born harpist David Watkins. The third and final part of his place-based Petite Suite, this piece, not quite two minutes long, seems to recapitulate what we've heard in the preceding pieces. Here, McDonald seems to say, is a summary statement of what the harp can do: linger on individual notes, contrast several at a time, deliver complex chords, suggest combinations of instruments, and present tone-poems.

All of these pieces could have crossover appeal, but the circles of 20th Century Harp's Venn diagram would be small. The crossover wouldn't be from classical to pop or rock but from a subgenre of classical--chamber music--to new age or mellow jazz or amorphously experimental, such as solo piano or solo guitar.

In a better world, this album would be a classic, at least on par with Brian Eno's ambient recordings or his collaborations with the guitarist Robert Fripp but more at the level of, oh, I don't know, name your favorite long-player that spawned multiple hits. In a better world, a world worth dreaming about, you'd walk into a grocery store or a shoe store and 20th Century Harp would be playing--and people would love it. Indeed, by listening to it they would become better people, more centered, more empathetic, with stronger neural connections.

If you are sold on the harp and the flute, be on the lookout for Susann McDonald and Louise Di Tullio's Masters of Flute and Harp, Vol. 1 (1976) and Vol. 2 (1978), both on Klavier and both strictly on LP.