415 Records and Roky Erickson

|

|

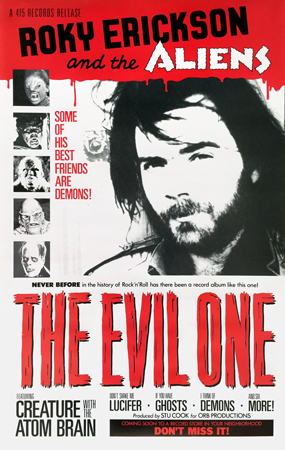

| Roky poster on right by Peter Soe | |

Book excerpt by Bill Kopp

(April 2022)

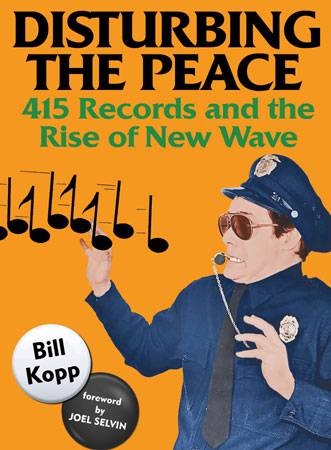

Based on nearly 100 interviews with the artists, industry execs, producers, friends, rivals, onlookers, journalists and hangers-on, Disturbing the Peace: 415 Records and the Rise of New Wave is published by HoZac Books. Music journalist Bill Kopp is also the author of Reinventing Pink Floyd: From Syd Barrett to The Dark Side of the Moon. Below is an excerpt from a chapter about how the label helped revive Roky Erickson's career at the beginning of the '80's.

Disturbing the Peace is available from HoZac Books: https://hozacrecords.com/product/disturbing-the-peace/

Craig Luckin had been Roky Erickson's manager for some time; he knew Stu Cook - bassist for Oakland heroes Creedence Clearwater Revival, now a budding producer - on a casual basis, and approached him about working with his mercurial client. "Craig loved Roky and was interested in his well-being; he was one of the few people that I met that ever was. He asked me if I'd be interested in producing some tracks with Roky, to see how it went," Cook recalls. "I said, 'Sure!' I had always been a fan."

Stu Cook hadn't met Roky previously, and their first meeting set the tone for their working relationship. "Roky was a very standoffish kind of guy, very quiet," Cook recalls. "He only spoke when he wanted something, generally. So we kind of eyeballed; we checked each other out, I guess." Cook describes that meeting as cordial, but emphasizes that he's not sure Erickson completely "got" it. "I don't think he understood fully what my role was to become," he says. "But over the period of time working with each other, we developed a pretty good working relationship. He began to trust me and let me make decisions without having to run everything by him every time."

Erickson was going through one of his more challenging times, Cook says. "He could sing and write and keep it together to do a live show, but he was too agitated to spend a lot of time in the recording environment. Sometimes he'd be incredibly coherent and focused and enthusiastic; other times, he'd be totally distracted or worried." The decision was made to split the project into two separate parts: instrumental work and vocals.

Cook rehearsed the band, working with them on arrangements. That exercise would prove valuable: it gave the producer insight into how the songs were structured, where lyrics were supposed to go, and other details. As it turned out, Cook would have to draw upon that knowledge to complete the album.

Cook was impressed with The Aliens. "They were solid players," he says. The band's drummer was John "Fuzzy Furioso" Oxendine, years later a member of a late-period lineup of Moby Grape. "Fuzzy was a solid drummer, and Morgan [Steven Morgan Burgess] was a really solid bass player," Cook says. "They played well together. Duane [Aslaken] was sort of the musical director of The Aliens, so he led the band pretty much for Roky; he knew what Roky wanted."

Stu Cook liked Bill Miller; he calls him a "straight shooter." But Cook readily admits that Miller represented his first encounter with an electric autoharp player. "Autoharp is an old Appalachian instrument, sort of finger piano-like," Cook explains. "You can't really play individual notes well." But Miller plugged it in. "When you put it through an amplifier and a bunch of distortion, it became a whole other monster," Cook says with a hearty laugh. "It sounded like something between a train wreck and a fire in a high rise!"

"I went all out to be versatile on the album," Miller says. "And I think I did that, to the point where no one ever knows what the autoharp sounds like."

In addition to the core band, Cook played bass on a few tracks in the studio, and a Frank Zappa sideman added his work to some songs. "Andre Lewis played synthesizers, and he did a monster job," Cook says. Other session musicians included SVT drummer Bill Gibson (later of Huey Lewis and the News) and SVT's singer-guitarist Brian Marnell on backing vocals.

Miller says that while most of the songs were pieced together after recording, a handful were performed live in the studio. When Roky and the Aliens convened at The Factory, they came ready to play "Bloody Hammer" and "Sputnik." And in a prescient move, they took a two-tiered approach for each song they cut. "We did an initial live take to get the backing tracks," Miller says. "We did one with Roky and then another one without him. We wanted to experiment to see if the ones that we did with Roky were going to be usable."

Additional recording took place at The Church, a studio in San Anselmo, a small town some 20 miles north of San Francisco. Roky wrote--or finished writing--several more songs during the studio sessions. Miller says that new songs included "I Walked With a Zombie," "Creature With the Atom Brain," "Night of the Vampire" and "I Think of Demons." He says that none of those songs had been played live before the sessions.

If those song titles suggest that the album was coalescing around a theme, that's an accurate impression. Roky had a deep fascination with classic horror. "I'm the one who originally encouraged that," says Miller. He recalls egging Roky on, challenging him, "You want to be a big star like Alice Cooper, right? Forget these folky songs! You're really good at that; we've got a whole album of that. But let's do that later when we're on top of the world." And he says Roky agreed. "He thought, 'Yeah, good idea!'"

Stu Cook thought it was a great idea. "It was Stu who made the decision to go horror all the way," Miller says. "It wasn't a suggestion; it was his idea to go strictly with the horror angle." He says that when Roky brought "I Walked With a Zombie" to the session, some of the other band members balked. "I really had to fight these guys to include it," Miller says. "It was Stu that made the decision, 'We're going to go with that. This makes sense.'"

Erickson got his inspiration from some fascinating and esoteric sources. Miller estimates that as many as three-quarters of the songs on The Evil One were influenced by and dedicated to French film director Jacques Tourneur. "He was like the David Lynch of the 1940s and '50s," Miller says. Tourneur directed 1942's Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie (1943) along with some 30 other feature films, and more than 20 short features. A particular inspiration was Tourneur's 1957 film, Night of the Demon.

Chris Knab and Butch Bridges of 415 Records surround Roky- photo by Chris Knab

Roky also had a great appreciation for classic sources, too. "Roky's song 'Night of the Vampire' is all based on Bram Stoker," Miller says. And at least some of his ideas came not from film nor literature, but from music. "Sputnik," a non-horror-themed tune included on The Evil One (but not its UK counterpart) is Erickson's answer to Joe Meek's 1962 classic, "Telstar."

Once basic tracks were done, Roky left California, returning to his native Texas under circumstances that--like much of his life--remain shrouded in a haze of confusion and vagueness. But there was still the matter of completing the vocals on the album. For that, Stu Cook would have to make a trip to the outskirts of Austin, Texas. "I had to get Roky out of the mental institution to do the lead vocals on some tracks," he says.

Craig Luckin had made arrangements so that the re-institutionalized Erickson could be "checked out" of Austin State Hospital to work on the vocal tracks with Cook. "He had to go in somebody's custody," Cook explains, "and that was Craig and me."

Cook says that when he first visited the hospital, he wanted to make a favorable impression upon the staff. "So I put on a sport coat," he chuckles. "And when I went to meet the doctor and get Roky checked out, all the patients thought I was a doctor! They were all hitting on me to get them out." He recalls that many patients were shuffling around, staring into space and talking to walls. "It reminded me of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," he says. "Roky was one of the guys [who] wandered around and smoked cigarettes all day long."

Cook brought Roky to Hound Sound, a downtown Austin studio owned by a songwriter he describes as "interesting...and a big acid freak." At first, the vocal sessions went smoothly. "Roky would be really focused," he says. "Then, after a couple hours, he would start to get unfocused and would immediately go to grinding on Craig: 'Craig, can I get a better apartment? Can you get me a better apartment?'" Luckin would respond, "Roky, you're not even living in an apartment." Eventually, things would go so far off the rails that Cook would call it a day; they'd try again tomorrow. In the meantime, Luckin would take Roky back to the hospital.

"I learned to spot when he was starting to lose focus," Cook says. Early on, he was reluctant to give orders to Erickson, but that changed as they worked together more. "I could tell when we'd done the best already," he says. "So I'd say, 'Let's not just crash around and waste time and money trying to top what we already know is going to be good stuff.'"

The sessions in California had been done on a 16-track machine; Cook brought those master tapes with him to Austin. He says that half of the 16 tracks had been taken up by drum parts. Bass, guitars and autoharp occupied one or more tracks each; that left no more than a few tracks for vocal overdubs in Texas. "So we would record two, three, four tracks of vocals, whatever we could," he says. Cook would save one track for a vocal composite. "You take the best word--or the best line or the best three words or whatever--from one performance, shoot them over to your open track, then you look through the other performances and see what you need," he explains. Afterward, with lyric sheet in hand, Cook would painstakingly go through Roky's vocal fragments. And Erickson never, ever sang a song the same way twice, Cook emphasizes. "I'd be picking out the best performances," he says.

But that work was done in the after hours, not when Roky was in the studio. "During the recording process, we'd get Roky on a good roll, and we didn't want to stop," Cook says. And he had a backup plan, too. "[Sometimes] we would run out of tracks, and we didn't want to stop to comp them down to a composite track," he explains. "So, we would run an [additional] 1/4-inch tape machine and just record to that, too. The second engineer would be taking notes: 'Actually, that's a good line. That's a good line.'" Everything was cataloged.

Because these extra vocal recordings weren't recorded on the same tape as the instrumental tracks, they weren't synchronized to the music. In those pre-digital recording days, matching the vocals up with the instruments required a technique called "wild syncing." Cook explains how it worked. "We'd start the 16-track machine, and we'd find a spot" where a vocal should be inserted. "We'd pre-roll back to the spot on the two-track machine, push 'play' on that, push 'play' on the 16-track, and hit 'record' for the part that we wanted." Then they hoped that everything matched up. "We had to hit it so that it fell into the groove of the song," Cook says, laughing at the memory. "You could do this all in a heartbeat today with Pro Tools."

Sometimes it would take multiple tries--more than half an hour of studio time--to get the proper synchronization. "You have to start one machine, start the other machine, and then they might be a couple of milliseconds off," Cook says. "That could make all the difference in the world to how the vocal feels; it's as important as if it's in tune, really."

With Roky Erickson's vocals, Cook says that he often had to ask himself, "Where do we roll back? Where do we start the pre-roll so that it ends up sounding like he actually sang it?" He says that he employed the wild sync technique for "many, many, many songs" that ended up on the finished record. "We finally got to the point where we just ran the tape all the time and recorded everything Roky ever said into the microphone," Cook says. "A line here, a couple words there, a scream; just whatever came out of him." The sessions yielded boxes and boxes of tapes. Those recordings documented everything, Cook says. "Roky giving me a hard time, telling jokes; me giving him production cues and ideas."

Cook strongly emphasizes that he doesn't deserve writing (or co-writing) credits for the songs on Roky's album. But his explanation of how the songs were assembled underscores just how important his role really was. "We were 'sampling' and rearranging Roky to make what I thought were the best songs," he says, describing his thought process at the time. "If I was Roky and I was writing the song, these are the two lines I'd put together to make this verse. It's the strongest spot, it moves the narrative forward, and it paints a picture that at least I can see. The next step takes me deeper into the picture." Cook was taking Roky's raw material and attempting to shape it into conventional song form.

According to Stu Cook, Roky was starting to deteriorate mentally at the time. "He was always sharper and more fun without the medication," he says. "But at a certain point, 'without the medication' got to be kind of reductive. And when he was on the medication, he felt terrible; it was pretty strong stuff. He didn't like taking it, because it interfered with his art. So it was always a struggle."

Cook readily acknowledges that the making of Roky Erickson and the Aliens/The Evil One was a lot of work. "But I wanted Roky to be happy with it," he says. "The whole time, I was thinking, 'What's Roky going to say when he hears this? Would he even know that he did it this way, or will he know that someone else has edited his work?'"

But Cook stands behind the methods he used to complete the album, and the results speak for themselves. "We made a decision," he says. "'Okay, Roky's going to blow our minds eventually. We just don't know when, so we have to capture it all.' That was the approach. It's like, 'Don't let anything slip by, because there might be a gem there.' And there was!"

Bill Miller gives great credit to Cook for his work on The Evil One. "Stu really worked hard on it," he says. "I think he wanted to do something that would stand the test of time. I'm really glad we worked with him. We really needed someone who's a stickler for knowing that it's going to work, and then making it work." Looking back at both the challenges of making the record and the brilliance of the finished work, Miller sums things up: "Roky kind of underestimated the power of his own songs," he says. "But maybe he also underestimated what it took to realize things."

Author Bill Kopp

and our tribute article to Roky