BEYOND VAPORWARE

How Memes Became the Folk Music of the New Weird Internet

by Jesse Jarnow

(April 2019)

The remixes are heard by millions. They go viral, shooting across Twitter and Facebook, influencing others to try their own hands. And yet recordings like "Africa (Vocals 1 Step Out of Key & Off Beat)" or "Smells Like Teen Spirit In A Major Key" barely register as hits, let alone as music. Soon relegated to the dustbin of forgotten memes, if they're taken seriously at all, they're generally classified on the outer fringes of the flourishing YouTube Poop scene, where media sources get treated with funny sounds and goofy processes.

And yet, these aren't merely punchlines. The results actually are music. And the recordings--like John Cage's ideas of indeterminacy or Lee Scratch Perry's stoned-out dubs--will go on to shape future generations of musicians, having already warped a generation towards understanding the true mutability of music. Like Woody Guthrie, they are musicians that have discovered that a song isn't a fixed set of words or chords or melodies or beats, just an idea that exists in the air at whatever moment anybody feels like grabbing it, and that they might take any song and change it around in absolutely any way they feel, to serve what purpose, and by whatever method.

Without marquee artists, though, the new hitmakers are less YouTube stars than they are the semi-anonymous balladeers yodeling in the content mines. Throw away any images of folk musicians strumming acoustic guitars or banjos, or even updating it with freaky lyrics or strange augmentations.

Much of the new folk music originates not in coffee houses, back porches, or country hollows, but is performed in dank subreddits, pseudonymous YouTube playlists, and spaced-out Tumblr hashtags -- traveling musical spirits with new millennial ways and means. One whole sub-genre was spawned by 2013's viral hit "Recovering My Religion," in which a Vimeo user named Major Scaled turned R.E.M.'s "Losing My Religion" into a major key (probably using Celemony Melodyne pitch correction software), scoring over a million views. A song that gets memed is a song that hasn't been forgotten.

Another new variation, emerging last year, is the explanatory-but-not "but every other beat is missing." As in: "The Sound of Silence but every other beat is missing." Like with "Recovering My Religion," it turns a familiar somber melody into something too surrealist to be whimsical, like an optical trick for the ear. "Highway To Hell but every other beat is missing," on the other hand, rewires the Young brothers' riffs into a radically weird whiplash groove, the sheer force of AC/DC carrying through even with missing parts, becoming something else in the process. And with "Highway To Hell" itself hard-coded into generations of riff writers, the new version is perhaps even more original, just waiting for a band of young math-rockers to cover it live.

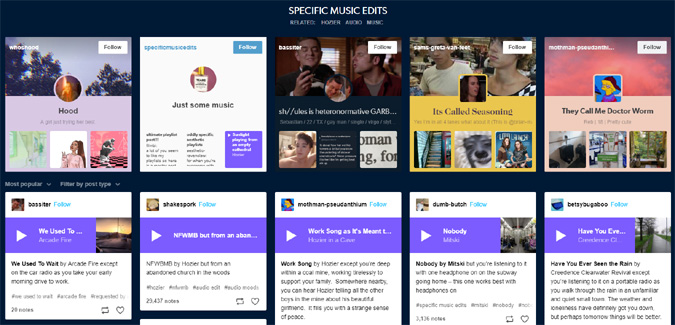

A more psychogeographical, ambient, and perhaps twee form is available on Tumblr, meanwhile, under the hashtag "#specific music edits." For example: byebrows' "christmas time is here by Vince Guaraldi except youre waiting for your mom in the parking lot of a grocery store during a snow storm" or messsybitch's "Israel Kamakawiwo'ole's cover of John Denver's Take Me Home, Country Roads except someone is playing it down the beach from you just after sunset as you watch the waves hit the shore and hear the coqui frogs start to come out and sing." Similar but different are mixes that simply copy-and-paste a favorite recording end-to-end for an hour or more, in the cases of Santo and Johnny's "Sleepwalk" and Keith Fullerton Whitman's transcendent extended "blend" mix of Fleetwood Mac's "Albatross."

Call the fresh twists vaporwave, screwed and chopped audio memes, or miscellaneous viral debris, but it has emerged as a new mode in the long and well-documented lineage of remix culture that originates equally in the chance operations of John Cage, the detournements of the Surrealists, the dub experiments of Kingston, and the turntablism of Daphne Oram, among others. But the new wave roots perhaps more directly from the even simpler hophead thrill of listening to a 45 rpm record slowed to 33 1/3 and the magical new spookiness opened therein, a practice which made the leap to the internet presumably not long after YouTube took off.

One slowed-down hit is Wanda Jackson's "Funnel of Love," spreading online a decade back, and heard in similar form in Jim Jarmusch's Only Lovers Left Alive. But the instinct to turn a song from "45 rpm to 33 1/3 rpm" is so ingrained in music culture that it comes as a built-in option in the popular free audio editing software Audacity (one of my personal favorites, discovered via thrift store and experimentation, is Peter Paul and Mary's 1967 version of John Denver's "Leaving On A Jet Plane," which I find unbearably and wonderfully sad).

Modernized a decade back more or less simultaneously into the screwed and chopped pleasures of Houston rap and into the theory-heavy thinkpiece-ready hypnogagic pop and/or vaporwave, the newest thrills go beyond remixes in numerous ways. Their simplicity removes artistic expression other than choosing the transformative process. Rather than carefully tweaking frequencies, extending breaks, or layering in new samples, these remixes are blunt, simple, and effective. It is a hands-off generative approach that Brian Eno would perhaps appreciate.

Another point of newness is that the music doesn't come from the music world, growing largely from the visual meme culture rather than the concerns of any particular scene. In Folk Culture in the Digital Age: The Emergent Dynamics of Human Interaction, digital folklorist Trevor J. Blank writes of "the folkloric process of repetition and variation." In the meme ecology, the repetition is just as much about the process as it is about the source material.

Tracing the "but with every other beat missing" concept, KnowYourMeme identifies it as deriving from a broader trend of "replacement remixes," going back to 2007 or so, where certain syllables of songs or videos would be swapped with comical sound effects. While pop music or theme songs were occasionally the material for some of the original replacement mixes, more often they drew from cartoons or other seemingly inexplicable sources with music just one tiny element of a vast pop cultural matrix. With less intentionality than remixes, they are perhaps no more than simple spells to cast on objects in the digital trashscape.

It was only the meme's 2016 resurgence when musical specimens began to become more frequent, including such earbenders as Vagidictoris's "All Star' by Smash Mouth, but all notes are C" (to these ears, an infinite improvement on the original) or "Eye Of The Tiger (Vocals: Every Note Is E)" (surprisingly like an ice cool indie rock tune).

One aspect that makes it folk music, is its characteristic of appearing in the wild, ready to be classified, with the sense that there might still be entire new continents to discover. Another aspect that makes it folk music, is seeing (and especially hearing) the way meme culture has turned its head from 21st century scraps to the received music of previous generations. After one too many trend pieces about millennials not knowing who some old rock star is, it's a refreshing twist to hear old favorites being reanimated into the present moment. The music of the 60's is now even further removed now than the strange pre-War folk and blues was to the original generations of rock musicians.

The songs are alive and always changing as they move through the hands of creators and re-creators, their meanings eventually belonging to none of them. Like the hackneyed image of Bob Dylan playing electrified ballads or the less-hackneyed way genuine folk archetypes like John Henry have persisted into the new dystopia (for example, as a character in the post-apocalyptic video game Wasteland 2), these interpretations of "timeless" songs generate an instant sense of strange and authentic folky displacement. It is not the folk music of the past, but the folk music of the now, untouched by ethnomusicologists, made for reasons besides "art" and often under perilous conditions, insofar as any could be disappeared instantly by a takedown notice from a vicious attorney-enabled algorithm.

The force behind the music feels more like an active group-mind than any directly connected music scene, a mob mentality drawn to the cause of fun, like Douglas Adams' Infinite Improbability Drive crossed with one of those all-too-clever automated Twitter-bots; which is to say, a small remaining happy corner of the old, weird internet. After 75-year-old Monkees guitarist Michael Nesmith spoke eloquently of his own vaporwave fandom, a new YouTube account dedicated "Nezwave" rapidly delivered the goods, slowing some of the cheesier tendencies of Nesmith's synth-heavy solo output into a luxurious slow-motion of pedal steel and Nesmith's wryness, and revealing the songs' hearts in new ways.

Like the best music of the 60's folk revival, some of it is smart and even caustic. Like a Mad magazine fold-in, "Killing In the Name but every other beat is missing" turns Rage Against the Machine into a cartoonishly Primus-like outfit. "Kill the name!" Tm Mrlo chants, which is a different and perhaps more important message. Unlike the music of the 60's folk revival, so far, it hardly wears its politics on its sleeve, except by accident. If it wasn't so palpably fun, all the fucking-with might be labeled (and dismissed) with the bleeding edge critical term, "interventionist art." Mostly, one gets the sense that those actually responsible for the fucking-with are more in it for the lulz -- which, in turn, makes them un-self-conscious musicians of the kind that the 60's folk revival (and subsequent music industry explosion) helped push to extinction.

The last years have seen the rise of an equivalent practice in academia, dubbed "glitching and deformance," seemingly unaware of all the glitching and deformance already occurring in the digital wilds. Distorting and deleting bits of code, altered images are then examined and interpreted. Originating in studies of visual art, it has made the move to music. "Messing things up helps us see things more accurately," writes historian Michael J. Kramer in his essay "Glitching History: Using Image Deformance to Rethink Agency and Authenticity in the 1960s American Folk Revival." As a historical process, Kramer suggests that glitched-out variations "destabilize" works, perhaps revealing "the dominant ideologies that get lodged in supposedly objective data such as a photographs."

Certainly, that's one way to explain what happens when listening to the two "deformances" of Bob Dylan's "Tangled Up in Blue" posted by Kramer's student Tanner Howard, where Howard converted an mp3 to a digital image, erased random chunks of data, and transformed it back into an mp3. By the time the first version gets to the second verse, the glitched Dylan sounds like he's being sucked into a blackhole, his voice fluttering as time bends around him, raging against the actual dying of the light, and trying to escape the certain fate of being deleted from the cultural memory, perhaps the sound a ghost might make while being sucked into the Ghostbusters' ghost trap. It's an unpleasant effect.

What it most resembles, sonically, is the so-called Electronic Voice Phenomenon, where the transmissions of ghosts are allegedly captured on tape, shaping and urging language out of noise. In the engaging recent book, Strange Frequencies: The Extraordinary Story of the Technological Quest For the Supernatural, Peter Bebergal describes the home-brewed technology of "spirit radios" designed to tune in the chaos between stations with the belief that it is the raw material by which voices might communicate from beyond the veil. "Our own consciousness becomes a kind of canvas for these voices--call them spirits if you want--to draw or write whatever messages we are able to process," he writes. "Think of a ghost box like an electronic tarot deck or the roll of an I Ching hexagram."

Comparing it to a modern form of cleromancy, Bebergal quotes electronic musician Kim Cascone on how a "glitch can form a brief rupture in the space-time continuum." It is the magic of the random, able to reassemble itself into meaning in the ear of the listener, and an artistic strategy as valid as any other. The LSD-obsessed 60's Texas band the 13th Floor Elevators likewise believed in the power of "the third voice," when two clashing sound sources revealed something new in the space between.

While unquestionably in line with avant-garde practices, it is the inherent hunt for the sublime, either through surrealism as actual laughs, that elevates it from meme-making to music, whether it means to do so, and folk in specific. Whether the sublime comes via absurdity or glitch, the idea of pairing the deformance with an already-familiar melody is a musical gesture that automatically loads it full of connotations for many potential listeners. It is folk music because, despite its transformations, it respects the song's origins, not trying to rewrite it, sample it, or steal it, but to acknowledge its power by making it the focus of the action.

So far, it's almost all novelty music, yes, and much of it disposable, at least until somebody hits on a variation that's just exactly perfect, at which point it becomes essential. No lulzing matter, recordings like Keith Fullerton Whitman's blend of Fleetwood Mac's "Albatross" are too good to be left on Soundcloud. I ripped an audio file immediately, and have luxuriated it in numerous times since. It will probably rank high on my year-end list of favorite recordings, as will some of the Mike Nezmeme cuts, pieces of music I actually will return to in years to come. I've long been a sucker for the pedal steel guitar, and each of those serves at least that interest. An even newer development is the way these memes have now bent back into actual musical performances, such as two specimens that emerged in the last weeks of 2018 -- Marc Giguere's "steve reich clapping music but on a snare with swing" and Isaac Schenkler's "The Moonlight Sonata but the bass is a bar late and the melody is a bar early." The latter, especially, becomes even dreamier in translation.

And there is Amadeus Code. Billed as an AI-based "songwriting assistant," one can use the app to process an existing hit (or an existing non-hit), and receive a whole batch of new melodies based on the harmonies of the original. Some might be chaotic, but some might sound great, and become the seed for new songs. Even robots can make the new folk music.

Maybe most importantly, in the same way that the folk revival may have inspired people to pick up acoustic guitars, perhaps the new glitches will inspire new ways of listening to other music -- imagining how it might sound better with every other beat removed, tuned to a different mode, maybe with a layer of light rain, and/or perhaps pitched down. There are ghosts everywhere, lurking inside every glitch and every song, waiting to sing.

Jesse Jarnow (@bourgwick) is the author of Wasn't That a Time: The Weavers, the Blacklist, and the Battle for the Soul of America (Da Capo, 2019), Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America (Da Capo, 2016), and Big Day Coming: Yo La Tengo and the Rise of Indie Rock (Gotham, 2012). He hosts the Frow Show on WFMU.