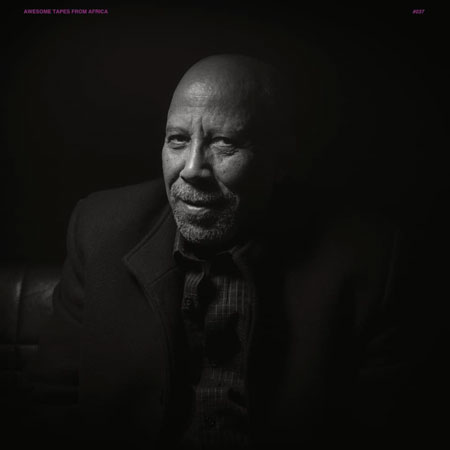

HAILU MERGIA

Altered Destinies: His Music of Past and Present

by Kevin Chesser

(April 2022)

When Jerusalem was captured by the Muslims in 1187 A.D., it is said that Lalibela, the emperor of Ethiopia's Zagwe dynasty, received a vision from heaven. In this vision, the emperor was given instructions to build a new Jerusalem, in the form of 11 rock-hewn churches, still standing today in the region of northern Ethiopia which now bears Lalibela's name.

Of the churches that make up this African Jerusalem, the Church of Saint George is widely considered to be the masterpiece. Carved from a single piece of volcanic rock, the structure was built first by digging a four sided trench, 80 feet deep, leaving a tower of solid rock at the center. This rock, cut by hand, would become the church, still a site of worship 800 years later.

The construction of the Hilton hotel in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia's sprawling capital, was in part inspired by the Church of St. George. It seems a paltry tribute to one of the world's great religious monuments, but it does make for an interesting entry point into the career of legendary organist, accordionist, and bandleader Hailu Mergia.

For Hailu Mergia and the Walias Band, the swinging nightlife scene inside the Addis Hilton was a sanctuary in its own right. In 1974, the Ethiopian monarchy, led by Emperor Haile Selassie for nearly 45 years, was at a point of reckoning. Selassie had shepherded Ethiopia out of the dark ages by advancing medicine, education, and infrastructure, but by the '70's, famine was spreading across the nation. Selassie's attempt to conceal the crisis from the outside world was a death knell of sorts, signaling the end for a monarchy which had been steadily falling out of favor for years. In 1974, a Marxist military junta called the Derg seized control of the government, giving way to the "Red Terror," a campaign of repression and violence which claimed between 10,000 and 75,000 lives. Across the street from the National Palace, where Selassie and family members were detained by Derg militants, the Walias entertained foreign dignitaries, American artists (Alice Coltrane and Duke Ellington among them) and members of the Ethiopian upper crust. To avoid being caught out after curfew, partygoers would arrive at the Hilton in the evening and remain there until dawn, while the Walias played on.

In the 1970's, Hailu Mergia and the Walias Band were at the bleeding edge of Ethiopian popular music, releasing jazz interpretations of songs from the traditional tezeta (Amharic for "nostalgia" or "memory") folk repertoire. They paved the way for records of entirely instrumental music as in-demand commodity, and their tunes eventually became ubiquitous throughout Ethiopian radio and television. Over the past decade, the Berlin-based Awesome Tapes from Africa label has revived the stalwart bandleader's catalogue, most recently with their reissue of the Walias Band's aptly titled 1974 record, Tezeta.

At first listen, Tezeta is almost numbingly smooth. It's little surprise these tunes have the aura of background music, given they were recorded in between marathon midnight-to-dawn sets at the Hilton. But whatever aspects of the music that might cause the listener to drift in and out of focus - hovering around a single chord, staying in the pocket, always in near orbit with the melody - are the same things that hypnotize and transport. 'Tezeta' refers to both a traditional ballad form as well as variations on the pentatonic scale around which much of Ethiopian music is constructed. In the west, we recognize the pentatonic scale as a sort of antidote to the major scale, calling to mind the plaintive language of the blues. Tezeta major and tezeta minor are part of a suite of scales that give Ethio-jazz its instantly recognizable but shapeshifting quality - at times joyful and bittersweet, dark and sultry at others. Mergia's work with the Walias Band blended these evocative traditional modes with the phrasing and grooves of jazz, creating a self-contained, wordless dialogue that spoke to past, present, and future simultaneously. But the choice to play instrumental music was not purely aesthetic - songs without words were less vulnerable to censorship, which helped preserve the band's career in revolution-era Ethiopia.

It's true that historical context brings Mergia and his work poignantly into focus, but the music is too this history and culture, or rather the transubstantiation of it. We enter this emotional happening through the tension between notes played and not played, the high and low tides of rhythm, and the traditional scales around which the music is based.

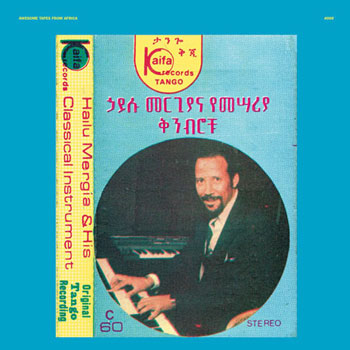

In 1981, Mergia and the Walias arrived in Washington D.C. for their first U.S. tour. Seeing an opportunity to escape the escalating violence at home and start anew, Mergia, along with several of his bandmates, elected to remain in the States. The primary musical record we have from Mergia at this time is 1985's Shemonmuanaye, re-released in 2013 by Awesome Tapes from Africa as Hailu Mergia & His Classical Instrument. Classical Instrument sees the prolific bandleader recast as one-man band, combining synth, accordion and drum machine to create a sound equal parts homespun and virtuosic. It's a fitting snapshot of this transitional time in Mergia's life, removed from the stark contrast of swanky hotel gigs and state violence that marked his career in Ethiopia. Where Mergia's '70s output was a staple of Ethiopian popular music, Classical Instrument was the sound of an expat working in relative isolation in a new country. For the next thirty years, Mergia would open a restaurant, drive a cab, and fly (mostly) under the radar.

Following a series of successful reissues by Awesome Tapes from Africa, Mergia has found a wider audience in the west, and, in the 2010s, began performing and touring again. Though this late career renaissance was interrupted by the pandemic, 2020 still saw the release of Yene Mircha, a six-song LP of tezeta styled melodies and laid back funk. 'Yene mircha' is Amharic for "my choice." fitting for an artist whose life has been nothing if not marked by the gravity of choice. Mergia's years of expatriation, along with possibly saving his life, have provided space to move, reflect, and regroup. His years spent driving a cab around D.C. are particularly compelling - in between fares, he'd grab a battery powered keyboard out of the trunk and practice. Through his years of semi-retirement and relative anonymity in the United States, music remained a constant.

Today in Ethiopia, conflict rages on. In 1991, ten years after Mergia arrived in the United States, the Tigray People's Liberation Front, a coalition representing ethnic Tigrayans marginalized in Ethiopia for generations, ousted the dictatorship established by the Derg. And just as the Derg did in the 70's, the T.P.L.F. commenced to seizing the control of the government through violence and the broad repression of speech. A slow breakdown of the T.P.L.F.'s power in the 2010s helped foment Ethiopia's present day civil war, with Tigrayans positioned as rebels once more, fighting to reclaim some control of the government from Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. In 2019, shortly before the conflict began to boil over, Ahmed was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work negotiating a treaty with Eritrea. Today's crisis has made short and bleak work of this accolade. With thousands dead, widespread food shortages, and a government-imposed blockade on humanitarian aid to the Tigray region, it is a sad truth that Ethiopia is known first to many the world over for the Mobius strip of its civil unrest.

What comfort do we claim to seek, by looking to our collective past of suffering and violent change? In the United States, nostalgia for our nation's past often feels grating and small-minded, not to mention inherently racist. But if we look at the nostalgic impulse as having three-parts - a longing for the past, filtered through the imperfect lens of memory, called forth in the present - then maybe we can better see it for the complex emotional process it is. In Mergia's music, engaging with the past is just as much an act of remembering as it is a means of reckoning with the present. When we hear stories of breaking out the keyboard in between cab fares, we gain some understanding into how this dynamic between past and present has expressed itself in his daily life. But Mergia, now well into his 70's, and continuing to revise, renew, and experiment with his craft, will tell you that he is of the moment. In an interview with OkayAfrica in 2021, he said "I just think of today, not the past. What can I get from the past? I don't get nothing from that, just memory." Close listeners are sure to hear a more complex dialogue in Mergia's catalogue, but at a certain point, context and interpretation give way to the pure pleasure of listening. The poet Terrance Hayes once wrote: "Brothers and sisters, when you spend your nights/out on a limb, there's a chance you'll fall in your sleep." For now, though, Mergia's dream, and ours, continues.