Jean Eichelberger Ivey

and the Peabody Computer Music Studios

by Daniel Barbiero

(February 2023)

Although she isn't well-known today, in the 1960's, she played an important role in helping to increase the accessibility of electronic music through workshops and performances,

and founded one of the first electronic music studios in a private conservatory.]

In conversation with interviewer Bruce Duffie in 1987, Jean Eichelberger Ivey was quite clear: "I am by no means entirely or even principally a composer of electronic music." To be sure, Ivey composed a large number of works that didn't incorporate electronic elements. And yet, even if she didn't want to be known exclusively or even mostly known for, her work with electronic music, the fact remains that for a particularly fertile period in the 1960's and early 1970's, she was very much involved with electronic music, not only as a composer, teacher, and advocate, but also as the founder of an institution dedicated to electronic music that continues to thrive today. The history of what she did for electronic music during that period is worth recalling.

Ivey (1923-2010), a native of Washington, D.C., began piano lessons at age six, and as she told George Udel of Forecast! magazine, began composing "almost immediately." She obtained a bachelor of arts degree from Trinity College in Washington in 1944, and a master's degree in piano from the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore in 1946. For the next decade or so, she taught music theory in the Washington-Baltimore area at Trinity, Peabody, and Catholic University, and went on to obtain a master's degree in composition from the Eastman School of Music in 1956. In the following two years, she gave performances on piano in Mexico, Germany, and Austria. When in Austria she met an American whom she married. Back in America, his academic positions brought them to New Orleans and Wichita, Kansas. During this period, Ivey found it difficult to continue her career as a performer and consequently turned increasingly to composition. In 1964, she began a doctoral program in composition at the University of Toronto, which she completed when she obtained her degree in 1972.

Ivey's early compositions were written in what she described as a tonal, neo-classical style influenced by Bartok and Ravel. In the 1960's, she was attracted to dodecaphonic composition and wrote a number of works in that style. It was also in the 1960's that she developed an interest in electronic music. A 1963 lecture by Milton Babbitt and Vladimir Ussachevsky of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center was particularly inspiring to her, and consequently, electronic composition was prominent among her studies at the University of Toronto.

What Ivey found appealing about electronic music was that as a new medium, it offered her the possibility of a new musical language that would allow her to express new ideas. As she told Duffie in her 1987 telephone interview, electronic music "contributes something that one can't readily do with the sounds of traditional performers...[it] causes you think up new rhythmic relations and durations [and] new new pitch relations and new timbres." She noted that working with tape "liberate[d]" her from standard notation and allowed her to develop ideas that standard notation may have channeled her away from. She also recognized that in putting electronic sounds down onto the fixed medium of tape, she would become a kind of performer in her own right, one who, like a musician realizing a score, was responsible for the actual sounds an audience would hear.

Although Ivey composed few purely electronic works, what she did produce was a vital part of the larger creative ferment and experimentation characteristic of the avant-garde music of the time. And one of her electronic compositions even found a mass audience.

Pinball

One of Ivey's earliest electronic works is the musique concrète composition Pinball. The piece was composed as the soundtrack to Montage V: How to Play Pinball (1963), a six minute-long experimental film directed by Wayne Sourbeer. How to Play Pinball was the fifth in a series of films produced by Montage Productions, a Wichita, Kansas group co-founded and led by Sourbeer that was dedicated to making films about people and places in Kansas. Ivey, who was living in Kansas at the time, had participated in an earlier Montage Productions film, 1962's Montage IV: The Garden of Eden, for which she composed a soundtrack for a conventional small instrumental ensemble of winds, brass, and percussion.

Sourbeer shot How to Play Pinball on location at a local business servicing pinball machines. For her soundtrack, Ivey went to the same location and made recordings of the sounds of some of the machines there. In the studio, she modified the recorded sound with filters and ring modulation, and manipulated the tape by splicing it, changing its speeds, and running it in reverse. The resulting work was what she described to Udel as "a kind of musical collage." The soundtrack provides the perfect complement to Sourbeer's montaged Kodachrome images of bumpers, flashing lights, and the artwork decorating the machines. Ivey's tape manipulations take the pinball machines' noises--their ringing bells, the metallic slap of the balls against flippers and bumpers--and by changing their pitches and durations mutates them into discordant melodies that at times sound like a carillon and other times like an aleatory sonata for toy piano. Overall, Ivey both conserves the machines' native sounds and raises them to a level of hyperreality that dramatizes the ebb and flow of a pinball game taking place within the sonic pandemonium of a bustling arcade. Pinball also was presented as a concert piece and was released on Folkways Records' 1967 album Electronic Music, a compilation of electronic works by composers associated with the Electronic Music Studio of the University of Toronto. Ivey was at the time working on her doctorate at Toronto, although her studio work on Pinball had been done not at Toronto but rather at the Electronic Music Studio at Brandeis University.

Continuous Form

A few years after Montage V, Ivey again collaborated with Sourbeer on a project commissioned by New York's educational television station, WNDT (later WNET) Channel 13. The station, which reached viewers in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, asked Sourbeer to create a film to be used during station breaks. WNDT had already experimented with using musical interludes to fill the brief periods of time between programs; Sourbeer's work would extend that experimentation into a new area. The person producing WNDT's station break experiments had previously worked with both Sourbeer and Ivey in Wichita. He was Richard J. Meyer, the station's Director of School Television Service. In Wichita he had been one of the members of Montage Productions, for which he had directed Montage IV: The Garden of Eden, which featured Sourbeer's cinematography and Ivey's non-electronic music.

As Meyer described the project in his article "television station breaks a new art form?" published in the Fall 1969 number of The Film Society of Lincoln Center's Film Comment, he gave Sourbeer the open-ended direction to create something suggestive of "growth and development." Sourbeer's resulting 28-minute-long film was then shown to Ivey, who composed a much shorter piece for tape at the State University of New York, Albany. The effect Meyer was hoping to create was inspired by the aleatory art recently in vogue in avant-garde circles. His concept was to "get a random design," which entailed having these incommensurably-lengthed visual and audio elements work together separately in order to produce miniature pieces that would feature different selections from the film and the tape in unpredictable combinations. Ivey's soundtrack was to be played in an endless loop--hence its name, Continuous Form--from which segments could be taken at random. Sourbeer's film was made to be sampled randomly as well. During station breaks, the film and tape were run independently of each other in order to generate chance juxtapositions of sound and image. The station breaks made from Sourbeer and Ivey's work were first used during the 1968-1969 television season, from just before 9 AM to 5 PM, and were eventually picked up by WGBH-TV, Boston's educational Channel 2 as well.

Continuous Form (ca. 1967) is a classic work of mid-1960s tape music. Apparently a hybrid of musique concrète and electronically generated sounds, the ten-minute-and-forty-three-second long piece opens with sounds mimicking the thunder and dripping water of an electrical storm, and then moves on to pulsating high-frequency tones swooping up and down in pitch, rattling metal, percolating mid-range tones, and back to artificial thunder. As a station break soundtrack Continuous Form was aired thousands of times, and one wonders what the average fifth grader in its captive audience thought of it. Did it make any young converts to avant-garde music? It would be nice to think so.

(Such as, for instance, me. As a WNDT-watching kid growing up in Connecticut, I must've heard Continuous Form, although at this far remove in time I just don't remember if I did. Still, more than fifty years later I listen to that stuff voluntarily, so who knows?)

The Electronic Music Workshop

The experimental station breaks that Meyer instituted at WNDT were meant to leverage art and ideas from the avant-garde in order to provide audio-visual content that would, in Meyer's words, "relate to youngsters and their teachers in this electronic age." With a similar goal in mind, and at around the same time that she created Continuous Form for Meyer, Ivey established an annual week-long summer workshop on electronic music for teachers at the Peabody Conservatory. The workshop, the first of which was held during the summer of 1967, was intended to demonstrate how, through hands-on work with equipment as simple as tape recorders, teachers could introduce students below the college level to electronic and avant-garde music, and open them up to learning more about sound in general. The first session attracted twelve participants, a number that tripled when the second session was held in the summer of 1968.

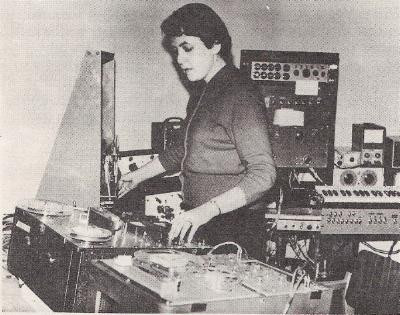

Ivey left a detailed account of the workshop in "Electronic Music Workshop for Teachers," published in Music Educators Journal in November, 1968. The program included some general discussions of sound properties and some audio exercises, one of which involved listening to Lejaren Hiller's Machine Music while reading along with the score. The centerpiece of the session consisted in equipment demonstrations. Ivey had on hand two tape recorders, apparently her own a phonograph and some early sound-generating and -modifying equipment made by Moog, which had been loaned by Peabody Director Charles Kent. The attendees experimented with the equipment, learned how to alter recorded sounds by looping, splicing, and reversing tape, and were introduced to techniques for overdubbing and mixing. At the end of the session, the group produced a minute-and-a-half-long, finished tape work.

In introducing avant-garde sounds and techniques to non-specialists, Ivey's electronic music workshops, like Meyer's experimental station breaks, were highly advanced, and even rather daring, for their time. Electronic music was still a new artform and rarely heard outside of small, avant-garde circles; opening it up to a more general audience, who were virtually guaranteed to find its sounds, at least initially, strange and possibly "unmusical," represented a double leap of faith--in the quality and validity of a still-developing form of music, and in the capacity and willingness of general listeners to appreciate its new and unfamiliar sounds. As Ivey understood, the key to electronic and avant-garde music gaining wider acceptance would likely be in acclimating young listeners to the new music being produced, and giving them an at least basic idea of how it was made. She hoped, in fact, that young students might find that tape music provided "a bridge to a whole world of music they thought they disliked."

The Peabody Electronic Music Studio

Ivey's summer workshops led directly to the founding, in fall 1969, of the Peabody Conservatory's Electronic Music Studio. As she explained in "An Electronic Music Studio in a Conservatory," her contribution to a colloquium on electronic music held at the 5th annual conference of the American Society of University Composers at Dartmouth in April 1970, it was in light of the success of the workshops that Peabody went ahead and establish a full-time music studio that would be used for regular courses during the school year. It was, she believed, one of the first electronic music studios to be located within a private, independent conservatory with a relatively low budget rather than in a larger, high-budget institution such as a university. It was not until 1977 that Peabody became affiliated with Johns Hopkins University.

To be sure, the new studio's initial complement of equipment was modest compared to what a larger institution, such as the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, could obtain. It consisted of two mid-priced Revox A-77 tape recorders, a Moog 1900 variable speed tape controller, and a set of Moog components for generating and modifying sound, a detailed inventory of which Ivey provided at the end of the published version of her presentation. Essentially, this was a variant of the Moog Synthesizer II. In addition, the studio was able to procure surplus equipment from Peabody's recording department--a microphone and an amplifier and speakers for hook-up to the tape recorders.

The purpose of the studio was to support composition, with a specific focus on tape composition, which was offered as a two-semester course. Originally open to a small group of seniors and graduate students, the course, in Ivey's words, was a "seminar in tape composition" where students could learn to "grapple with actual problems of tape composition." After being given an introduction to the equipment and to tape techniques, the students were to create one finished tape composition per semester. During the studio's first year, these student compositions were presented on concert programs.

Ivey's Cortege for Charles Kent was the first work created in the new studio; it was composed in 1969 in memory of the former Peabody Director, who had died that year. The piece is a purely electronic work incorporating sounds generated by the Moog synthesizer; Ivey arranged individual events in layers to create a contrapuntal effect further underlined by dramatic spatialization across the stereo field. The piece isn't particularly funereal except for a recurrent low-frequency, reverberant sound that could be taken as representing the tolling of a bell.

The Studio as Legacy

Cortege for Charles Kent appeared on Ivey's first monograph album, Music by Jean Eichelberger Ivey for Voices, Instruments, and Tape, released by Folkways Records in 1973. The album, which in a sense represents the culmination of Ivey's 1960's work with electronic music, contains four pieces composed from 1969-1972. The memorial piece for Kent is the only purely electronic work on the album; the other three compositions demonstrate Ivey's turn after 1970 toward using tape as an element alongside of the human voice or as an instrument among standard orchestral instruments. Indeed, during the 1970's, she composed a number of works integrating tape with live performers: Terminus (1970) for mezzo-soprano and tape; Three Songs of Night (1971) for voice, chamber ensemble, and tape; Aldebaran (1972) for viola and tape; Hera Hung from the Sky (1973) for mezzo-soprano, chamber orchestra, and tape; Testament of Eve (1976) for voice, orchestra and tape; Sea Change (1979), for orchestra and tape.

In 1969, Ivey joined the staff at Peabody, obtaining tenure in 1976. She stayed with the institution until her retirement in 1997. From 1969 until her retirement, she was Director of the Electronic Music Studio, which grew to include a Computer Music Studio, founded and directed by Geoffrey Wright in 1982. The two studios were merged in 1989 under the computer studio's name.

Just as much as the work she composed, the studio is her legacy, and perhaps its greatest part, given the genuine vocation she had for teaching. The Electronic Music Studio had always been more than a place for her to compose; it was a place where she taught succeeding generations of composers to create music with technologies that changed with the times. It was also a place that she foresaw as playing a role in introducing a larger audience to electronic music, through concerts, lectures, and demonstrations.

Ultimately, Ivey saw electronic music--its sounds, its methods, the problems it raised--as relevant to the development of creativity in non-composers as well as composers. As she told the American Society of University Composers in April 1970, repeating something she wrote in "Electronic Music Workshop for Teachers":

Genuine creativity involves being open to the new and the untried. The new medium of electronic music, with its vast possibilities and its lack of a long, well-formulated tradition, may call forth, better than an older medium, a sense of what it is to deal with the unfamiliar in an open and original way.

Many thanks to Matt Testa, Archivist at the Peabody Institute's Arthur Friedheim Library, for his generous help in providing information about Ivey and for reviewing a draft of this piece. In fact it was Matt who inspired this piece, and introduced me to Ivey's work, when he mentioned in conversation that he was digitizing some archival recordings of her compositions.

Sources cited:

Jean Eichelberger Ivey, "An Electronic Music Studio in a Conservatory," American Society of University Composers, Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Conference, April 1970, pp. 38-46.

Jean Eichelberger Ivey, "Electronic Music Workshop for Teachers," Music Educators Journal, Nov. 1968, Vol. 55 No. 3, pp. 91-93 (downloaded from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2307/3392386)

Jean Eichelberger Ivey, interview with Bruce Duffie, 1987, http://www.bruceduffie.com/ivey.html

Richard J. Meyer, "television station breaks a new art form?", Film Comment, Fall 1969, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 62-65 (downloaded from https://www.jstor.org/stable/43754517)

George Udel, "Music by Jean Eichelberger Ivey, Forecast!, February 1975, pp. 46-47 (downloaded from https://worldradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Stations/IDX/City-Radio-Magazines-IDX/FM-Forecast-1975-02-OCR-Page-0044.pdf)