Miles Davis

Some observations about his post-retirement live years

by Jeff Wilson

(August 2009)

He seemed so short. And dark—darker than I realized from photographs in magazines and on album covers, with chiseled features and solemn eyes. Because a battery-charged microphone was clipped to the bell of his trumpet, he was, unlike the rest of his seven-piece band, free to wander. Seldom facing the audience, he moved from one side of the stage to the other, passing the other musicians while his eyes stayed fixed on the path he was following until, almost out of sight from the audience, he turned. His head leaning forward so his trumpet faced down, he had an almost monk-like concentration, as if were listening as closely as possible to each note as it echoed off the stage.

His flashy seventies threads had been replaced by a maroon jumpsuit and wooden clogs that, as he pranced around the stage one micro-step at a time, slid softly across the floor. Mostly hidden under a white cap just big enough to cover the top of his head, his black hair was cropped as short as it was in the fifties.

He never smiled. And seemed fragile. Like he was in pain.

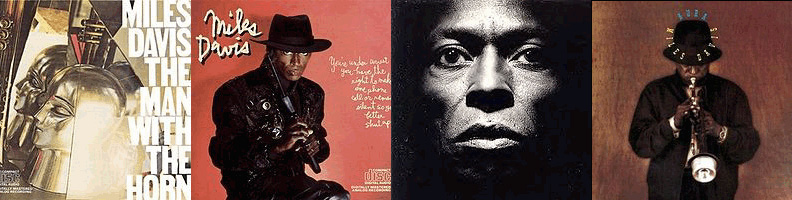

A few weeks before the concert I stumbled across, at a used record store, a promo copy of The Man With a Horn. Begrudgingly playing an Isaac Hayes cut I'd requested, the store employee rolled his eyes after I said, "Wow! A new Miles Davis album!" Glancing disdainfully at the Isaac Hayes record spinning around on a now-tainted turntable, the employees said, "Well, if you like that, who knows, you might like that too."

"Not impressed?"

"Rehashed Bitches Brew," was his encapsulated review.

I bought the record anyway, aware that drawing approval from record store employees can be a difficult task indeed. There was no Internet then, and news traveled at a slower pace. I knew, from a Rolling Stone article in the mid-seventies, that Miles was facing some health issues, and I also sensed, in the late seventies, that albums like Big Fun and Agharta were having a harder time getting released. For me and most Miles Davis fans, the years between 1975 and 1981 were a black hole, and the new album came as a surprise—and, a few weeks later, the news that Miles Davis would play Cincinnati was a huge surprise.

Music Hall seats 3,500, and it was about half full that night—which made sense considering how little press there was thus far about a comeback. Still, there was an air of intrigue and excitement, as many in the crowd had never seen Miles Davis, and even the people who had seen him were curious about what seemed like a sudden return. At that point I mostly listened to the funky electric music records Miles made in the late sixties and early seventies. My favorite was Bitches Brew, not because it was as revolutionary as Ralph Gleason's liner notes claimed, but because it wasn't (to me, anyway). What I heard was a room full of musicians tentatively feeling their way toward a new type of music. There was some naivete there, as exemplified by Miles telling—of all people—John McLaughlin at beginning of the session, "Play the guitar like you don't know how to play the guitar." This was not the record where future jazz-fusion heroes played their most boisterous and mind-blowing solos. It was more about creating a tapestry, blending sounds together into a collage of styles that had as its visual compliment Mati Klarwein's fine album cover.

The exception was the leader of the band. On Bitches Brew, Miles played the hell out of his trumpet. Nothing he recorded before that—including his previous forays into fusion—anticipated such spirited, in-your-face, wildly creative trumpet playing. After all, this was the musician who as a young man turned jazz trumpet on its head by, instead of blowing loud and fast, played in a way that was described as "walking on eggshells." That would not describe his playing on "Miles Chases the Voodoo Down" or "Pharaoh's Dance," however. Words like sensual, colorful, powerful, and spirited begin to describe his playing on that record—and ultra-confident.

His playing the first time I saw him was nowhere near that muscular. And while the context was similar, nothing he played from his new album that night was as memorable as such earlier electric gems as say, "Jack Johnson" or "Great Expectations." But I liked his band. I liked the chemistry, the sound, and the interaction between the musicians. His group was a study in contrasts—and how different strands can come together and create something more interesting than the individual parts. It broke down racially. Augmented by a percussionist, the rhythm section, with Marcus Miller on bass and Al Foster on drums, both black, couldn't have been more solid—or more flexible—or more economical. Where some rhythm sections want to fill in all the spaces, Marcus and Al constantly created space without ever losing the pulse. If they were minimalists, the young, long-haired white guys were abstract expressionists, favoring sheets of sound and lots and lots of notes. There was something wild and unpolished about them—and it worked.

So where did Miles fit into all this? He stayed in synch with the African-American (and African) hertiage, which meant that even though the music was loud and funky, his playing had more in common with his early days, when he was renowned for his understatement and introspective feel. The thing I most enjoyed about that concert was the sound of his trumpet. Almost always using a mute, he nailed that sad, haunting tone characteristic of his early work.

The performance that night (September 18, 1981) was brief: the first set clocked in at forty-five minutes, the second was shorter, and there was no encore. The set list consisted entirely of songs from the newly released The Man With the Horn except the closer, which was the best song of the night. After the show everyone asked everyone else what it was. It turned out it had not yet been released, but it showed up—two versions, actually—on the next album, We Want Miles, as "Jean Pierre." Modulating between what sounds like the melody to a kid's song and on a lopsided funk riff, it leaves the soloist a world of options. Bill Evans played a flurry of notes on soprano sax while Miles was all about insinuation and understatement. That song was a tease really—-an indication that, although the first album and first tour since his six-year break seemed tentative, he was finding his way.

That first tour was grueling, but his stamina increased, and We Want Miles was better than people expected it to be. The lengthy blues workout on Star People was good enough that a store employee who was otherwise a staunch electric Miles snob refused to sell me a promo copy after he sampled it in the store. And while Decoy and You're Under Arrest didn't do much for me, when I heard he was playing the Palace Theater in Columbus, Ohio shortly after Arrest I decided to make the road trip. One nice thing about this phase of Miles' career was you never knew who would walk out on stage with him. And that night (March 1986) who (re)appeared but Michael Stern—who had been replaced by John Scofield, a more subtle player with a jazzier feel. Wearing black leather and still sporting shoulder length hair and a Stratocaster, Stern looked more like a rock and roller than ever.

His playing that night was that much more turbo-charged than it was on the The Man With a Horn tour—and fit right in with a nine-piece band, which was also more aggressive. The animated and highly mobile percussionist Marilyn Mazur stayed quite busy that evening, adding layers to a canvas that was already quite full.

So was this high-octane Miles, as was often suggested, a ploy to sell more records? A look around the Palace Theater suggested otherwise. At this well-attended show, the audience mostly consisted of well-dressed solidly middle-class blacks and whites, many of them couples, and it seemed safe to assume that much of the music Miles played that night was edgier than what they listened to on their car stereos on the way to the show. Jazz guitar legend Jim Hall praised a concert from this period as "Bartok with a backbeat." Bartok is hardly a crowd pleaser, and the backbeat that night was stronger than it need to be, but the audience that night was still enthusiastic.

Walking faster than the first time I saw him and sporting fancier clothes and longer hair and Sly Stone-sized sunglasses, Miles seemed ten years younger and sounded healthy. During the first half-dozen songs, raw energy and blazing tempos were the norm, and Miles met the fury head-on. This was easily the loudest Miles show I attended—so the silence was that much more intense when, after a half-dozen songs, Miles stormed off the stage. The other band members looked at each other, stood there for a couple minutes, then left the stage as well. And the people in the audience looked at each other and said... is it over? Staying in our seats, we watched band members come out and talk to stage hands who shook their heads sadly, as apologetic as they were useless.

Twenty minutes later the lights dimmed again, and the band returned. Obviously though, what was still bothering Miles before was still bothering him, and the rest of the band seemed nervous, and the possibility that magic would occur that evening was null. Not surprisingly, there was no encore.

Although some of the songs seemed to run together that night, I liked the sheer physicality of the show as well as the dense layers of sound. And a couple of as-yet-unreleased songs stuck out: one had an ominous melody and a funky groove; the other was a hypnotic, Spanish-tinged ballad. A few weeks later, the saxophonist from the Columbus concert, Bob Berg, played jazz standards with a piano trio at a club in Cincinnati called the Greenwich Tavern. Between sets, I asked him about the Columbus show. He said Miles couldn't hear himself through the monitor, nor could anyone else. And he said both of those songs that I described would appear on an album that was recorded but had not yet been released. From Tutu (released September 1986), the songs were the title track and "Portia."

Tutu was still in its infancy when Miles returned to Cincinnati's Music Hall (January 1987). This was one of four shows guitarist Hiram Bullock played with Miles—and bassist Daryl Jones was back in the lineup. Both made valuable contributions. Bullock was particularly effective on the slow blues concoction that had become a staple of Miles concerts. Many people recognized him from the house band with David Letterman, and his playful, fun-loving performing style went overly well. During his blues solo, Bullock walked over to one end of the stage, glanced briefly at a No Smoking sign, and, flashing a cocky smile, got some well-deserved laughs.

Daryl Jones was the wild card that, by early in the set, made it clear that this could be an exceptional show. Shortly before that concert, I saw Jones perform with Sting. Much fuss had been made about a pop star forming a group filled with musicians from the jazz and jazz-fusion world, but ultimately musical backgrounds had little influence over Sting's sound—and Jones' role seemed very subdued. Without overplaying or showing off, Jones had a huge influence over the way the Miles Davis band sounded that evening. Compared to the Columbus concert just a few months before, the music that night was much less busy and had a less frenetic backbeat, with more restraint from the percussionists and keyboardists. This allowed Jones to establish a groove that was rock solid, yet with a gorgeous sound and harmonic richness and a great melodic sense.

Right away Miles tuned into Jones, and he tuned into Miles. Even with a pair of dark sunglasses, Miles had a way of facing his fellow band members in a way that would cause more sensitive souls to change professions. It could be daunting, but it also inspired musicians to dig deeper. During the face-offs between these two musicians, Miles seemed to be sending a message—and it was clear to everyone who attended the show that Daryl Jones was paying attention.

The band played a well-paced set, interspersing more fiery fare like the opener "Jack Johnson" with slow blues and ballads such as "Time After Time" and "Human Nature." Toward the middle of the show, the band uncorked a "Tutu" that, due in part to Jones' thumb (hopefully it's insured), was that much funkier and edgier than the studio version. Near the end of the concert the band played what I guessed to be a radical reworking of "Portia"- actually it was a beautiful Spanish-tinged ballad from the soundtrack to Dingo.

So far, so good—good enough that when the band returned for an encore expectations were high. That's when Miles pulled out "Portia"—not a radical reworking, but a tremendous live version that featured his best solo of this night. As he left the stage the band cranked up the volume while Bob Berg and Hiram Bullock soloed simultaneously.

After they left the stage the volume dropped considerably. Left behind were the drummers, the percussionist, the keyboardist—and Daryl Jones, who played a solo that was as compelling as the one by Miles. It offered clear evidence that the message Miles was trying to impart had been received.

Before Miles Davis died, almost every review I read of his early electric work was negative. Since he died the press is almost all positive, with lots of long, massively researched articles that delve into all the minutia of recording sessions and concerts that were previously panned. It's amazing what a flip-flop has occurred. So why did so many critics hate his work originally, and why now, does it receive so much praise?

Often such answers come down to who's doing the writing. To be sure, jazz fusion had its fans—lots, actually—but rarely were they critics. Jazz traditionalists scorned fusion, which, after he went there, Miles played almost exclusively. The odds of Miles winning over conservative jazz critics were slim—and when it came time to review either a Miles concert or an album, that was generally who sat behind the typewriter. Some writers from the avant-garde camp praised the electric work of, say, Ornette Coleman, James Blood Ulmer, and Sonny Sharrock, and with time, these writers looked back fondly on someone who was swimming in the same stream. Then funk become huge—bigger, in fact, than when the funk icons actually played it, and that raised interest in earlier electric Miles.

It's hard to imagine that the music Miles played during his last ten years would please any of these camps. It wasn't "neotrad" or "rebop," it wasn't as experimental as his previous electric work, and although a lot of it was funky, the period of funk that hipsters rave about came earlier. That said, the qualities that defined Miles in previous decades also applied to his final phase. In his liner notes to Bitches Brew, Ralph Gleason praised Miles for his serendipity, and that word quickly comes to mind when reviewing the last phase of his career. Was there another period when Miles experimented more than in the eighties and early nineties? It wasn't just that he changed styles from album to album; often, all you had to do was listen to the next cut on a record to hear a different style of music. Collaborating with everyone from Prince to Palle Mikkelborg, he was considerably more restless than most musicians half his age—and that's especially true for the most conservative era in the history of jazz. And if some of his work was commercially successful, it's hard to accuse him of selling out when the reason he left Columbia was its reluctance to release his adventurous Aura. That record is very much the work of a musician still exploring.

And the word "serendipity" didn't just apply to his recordings. Increasingly juggling musicians, he continued to experiment with different line-ups during his tours, with varying results—and his final show in Cincinnati made it clear just how powerful a Miles Davis concert could be when all the pistons were firing.