Nuff Lyrics:

Classic Reggae Songs in Historical Perspective

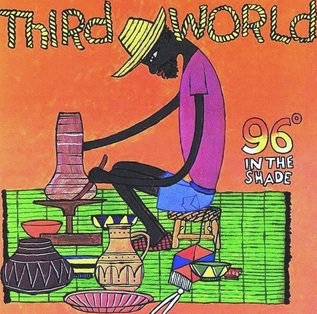

Part 2: "96° in the Shade (1865)"

by Eric Doumerc

(June 2023)

real hot in the shade.

Said it was 96° in the shade,

Ten thousand soldiers on parade,

Taking I and I to meet a big fat boy

Sent from overseas

[In] the Queen's employ.

Excellency, before you I come

With my representation,

You know where I'm coming from.

You caught me on the loose,

Fighting to be free.

Now you show me a noose

On the cotton tree:

Entertainment for you,

Martyrdom for me.

96 ° in the shade,

real hot in the shade.

Some may suffer and some may burn,

But I know that one day my people will learn.

As sure as the sun shines way up in the sky,

Today I stand here a victim; the truth will never die.

Third World's "96° in the Shade," also known by its alternative title ("1865"), is one of the best-known reggae songs thanks to its catchy melody and its revolutionary message. The song was released in 1977 on the band's second album, also titled 96° in the Shade, and has been part of the band's live repertoire for many years. "96° in the Shade" is a powerful evocation of a sad episode in Jamaican history, that is the repression by the colonial authority of a peasants' revolt in 1865 (the Morant Bay Rebellion).

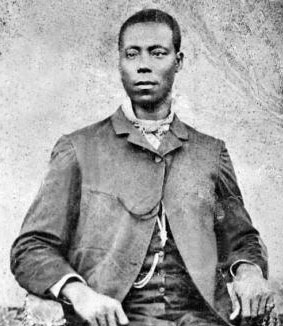

The rebellion broke out after a series of incidents and demonstrations which took place in early October 1865. These demonstrations were led by Paul Bogle, a black peasant and Baptist preacher who marched into Morant Bay on October 7th at the head of an army of 200 men. Bogle left his men in the square and went into the courthouse where several cases were being heard. Apparently, Bogle was involved in an attempt to obstruct the course of justice as he tried to stop the police performing their duty.

Paul Bogle

After this incident, Bogle and his men went back to the hills (to Stony Gut), but warrants were issued for their arrests and policemen came for them. These black policemen were beaten up and made to swear that they would support the blacks in their fight against the whites. They were allowed to go back to Morant Bay, but they had heard that Bogle's men were planning to march on Morant Bay on the next day (October 10th). On that day, Bogle's army went to Morant Bay and went straight to the vestry where a meeting was in progress.

Eighteen people were killed including Baron Von Keteholdt, the local Custos and Magistrate, 31 people were wounded, and 51 prisoners were released from the local jail. But before being killed, Keteholdt had sent a letter to Governor Eyre and to the Morant Bay police. Accordingly, Governor Eyre asked for reinforcements and the local militia, together with seamen, marines, troops and Maroons began to put down the rebellion.

Eyre declared martial law and more than 1,000 houses were burnt to the ground. There was widespread looting and killing. Many prisoners were shot, hanged or flogged without trial or without any evidence produced to convict them. Many people who had not supported the rebellion were killed. The repression was brutal.

Governor Eyre managed to have George William Gordon accused of high treason and hanged. Gordon was the son of a white man and a black slave. He was a successful merchant who had done well and earned a seat on the Jamaican House of Assembly. He was also a member of the local vestry. He had described Governor Eyre as a "bad man." So Governor Eyre saw an opportunity to get rid of a powerful rival and had him taken to Morant Bay where martial law had been declared so that he would be tried by court-martial. George William Gordon was hanged on October 12th 1865. On the same day, Paul Bogle was captured and hanged.

The immediate outcome of the "rebellion" was that Jamaica agreed to suspend its constitution and to become a Crown Colony, directly ruled by the Crown. They did so in order to prevent coloured and black Jamaicans to gain seats on the House of Assembly and to challenge their ascendancy: the rebellion struck fear into white (and some coloured) Jamaicans.

When interviewed by the reggae historian David Katz, William "Bunny Rugs" Clark, Third World's lead vocalist, said that the song was "strictly about Paul Bogle, who was hanged in Jamaica for leading a revolution against the English for equal rights and justice for his people. That was a true story, and the year for that was 1865. Paul Bogle is one of Jamaica's national heroes, so the same way Burning Spear sings about Marcus Garvey, we sing about Paul Bogle."

The reference to Burning Spear is interesting and shows that Reggae lyricists then considered themselves as popular historians and consciousness raisers. The song was released in 1977, the year when Michael Manley's government made both Paul Bogle and George William Gordon into national heroes. Since coming to power in 1972, the government had been insisting on the value of education and had launched a literacy programme to educate the Jamaican people. Making Bogle and Gordon National Heroes was another way of making Jamaicans aware of their history. Third World's song must have had a tremendous impact for this reason too.

The Morant Bay Rebellion gets a mention in other Jamaican reggae songs in which Paul Bogle and George William Gordon take centre stage. Indeed Bob Marley's "So Much Things to Say" (on Exodus, 1977) has lines that go "I'll never forget no way, they turned their backs on Paul Bogle" and Culture's "Innocent Blood" (available on Culture's Africa Stand Alone, 1978 and Cumbolo, 1979) refers to Paul Bogle who "was from Stony Gut." Prince Far I's "Jamaican Heroes" (on Prince Far I's Jamaican Heroes LP, 1980) mentions Gordon and Bogle too.

References:

Hart, Richard. From Occupation to Independence - A Short History of the Peoples of the English-Speaking Caribbean Region. London: Pluto Press, 1998.

Katz, David. Solid Foundation - An Oral History of Reggae. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2003.