THE SEVENTH SONS

Fred Neil and his raga rock friends

60's folk, blues & raga rock

by Tony Ruiz

(August 2022)

Jim Rooney1

What to say and what not, of whom and as to what, to what extent to say it are questions that continually arise around The Seventh Sons. It becomes an uphill battle to write about something that no one has written before with any depth. This two-part essay seeks to right these wrongs and give this seminal band its due.

Searching for information about the members of the Seventh Sons online, there are hardly any avenue of investigation to follow- Serge Katzan, for instance, almost does not exist there, which is kind of disappointing, but also kind of fascinating and mysterious. But it's also the band that stands concealed in the story of the members themselves. Reading bassist Steve DeNaut's obituary (his only one on the Internet), the Seventh Sons name is conspicuous by its absence- there's no reference despite the fact that one old friend mentioned that DeNaut lived in Greenwich Village for ten years. Perhaps more flagrantly, the bio profile of Buzzy Linhart that has been on AllMusic Guide for years follows the same trend, skipping the period of Linhart's relationship with the band, without even naming it, as if they never existed.

Sometimes, the confusion is provided by the members themselves. The band used to be remembered as the first incarnation of Buzzy Linhart band, as he undertook a career as solo artists, later reaching commercial success in the 1970's. Linhart kept a particular presence in The Seventh Sons, ostensibly as a leader since his name appeared underlined when they started as 'The Buzz Linhart Trio.' After that, his name was featured in different ways alongside the band name, as Buzz Linhart & The Seventh Sons, even as The Seventh Sons featuring Buzzy Linhart or as Fred Neil with Buzz Linhart. In fact, there were weeks in which he played as a soloist with the Sons, and with the Sons backing Fred Neil. Maybe this way of including the name of the band in the bills, as if they were mere accompaniment, also contributed to the way in which the group's passage through history has been obscured. It can be seen from the outset how Buzzy's strategy and vision may not have coincided with that of the group, especially with that of Serge Katzan, the drummer who would also be the combo's manager. But that is another story.

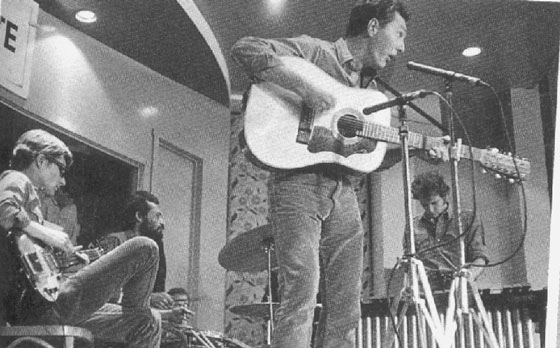

July 1, 1965. Fred Neil & The Buzz Linhart Trio play at the Palisades Amusement Park in New Jersey. One picture (see above) shot by photographer and Hit Parader editor Don Paulsen was included in the article "The Last Great Undiscovered Greenwich Village Folk Legend," written by Simon Woodsworth in the mid 1990's2. The quartet onstage includes Fred standing (a rarity for him) close to the mic, about to sing and playing his huge 12-string guitar, tall and secure from a low angle. He is backed on the left by Steve DeNaut on electric bass, seated in shades in a cool position, with crossed legs, just chasing Fred's beat without getting tired. Serge Katzan is almost hidden in the center behind the drums (he usually was photographed playing percussion), while Buzzy can be seen on right, concentrating intensely, looking down at the vibes that he's playing.

In the late 1990's, in the emerging world of the internet, The Seventh Sons began to be noted, related to Fred Neil and as the backing band who did ragas, surrounded in a cloud of mystery. There were no recordings though. But the invocation of the moment that contains the image does not even depend on the presumed talent that the quartet could display at the time the photo was taken. It's more about how it hovers as a pressure in the air, breaking down the sound possibilities. The hunger for a wild sensation: what it could sound like is maybe what this listener will always look for.

Probably the ongoing disclosure of Fred Neil's life and career has served to uncover a band that otherwise would not have gained its due. In short, this article about The Seventh Sons would not have existed without three names in particular. There was Fred Neil, who was encouraged to play with them when were still unknown; Don Paulsen, who chronicled the series of events in Hit Parader mag, and even photographed them, and lastly, Raga, the only album The Seventh Sons launched in four years.

The Seventh Sons were among that group of 1960's North American psych-folk acts that released only one album, leaving behind a ephemeral and quite hazy legacy from the decade - compare that to Alexander 'Skip' Spence or Dino Valenti who, unlike The Sons, have enjoyed impression exhuming of their material.

Part of the confusion about them is because they were called The Buzz Linhart Trio at the beginning. Their short cult existence (1964-1968) sounds even stranger yet given that their album, Raga (ESP 1078, 1967), contains one eponymous piece of music sliced in two halves for vinyl purposes, a casualty that keep on amounting to this one issued track being their aural legacy during their four years of existence. No singles either. Besides, it must be noted that the LP was released by ESP, the label that had only launched folk recordings by The Fugs, Pearls Before Swine, Ed Askew and Randy Burns, amid dozens of free jazz and avant-garde albums. According to 1960's music scholar Richie Unterberger, it "was the kind of label that put out music so daring, or just plain weird, that few other companies would touch it."3

Despite a notable, if partly unknown, gigography, and besides a few demos and reel to reel tapes that the band recorded indoors, none of their material otherwise has circulated on bootleg. So given the faint official history credited to the group, other details related to the band are somewhat incomplete, needless to say, as well as mysterious, vague and ambiguous.

(It's worth noting at this point master Chicago bluesman/songwriter Willie Dixon, who penned the song "The Seventh Son" (covered by Willie Mabon, Mose Allison and Johnny Rivers). According to Dixon himself, the two-word expression comes in from "...New Orleans and Algiers, Louisiana, they have these people calling themselves born for good luck because they're the seventh sister or seventh brother or the seventh child. The world has made a pattern out of this seven as a lucky number. Most people think the seventh child has the extra wisdom and knowledge to influence other people."4)

The Seventh Sons were not just the Fred Neil backing band though. Rather, they were mostly a mutant group of musicians who transcended the historical moment by devoting their efforts to making music together, including folk-rock, blues-rock and drone-based ragas. Mostly, they distilled huge segments of vivid music in continuous motion, with no place of origin, being more Eastern than Western, more self-involved than aimed at getting an audience. They can also be seen as a symbol of many American bands in the mid-1960's, divided in to several directions and composed of opposing aspirations, characters, personalities, inspirations and influences. One day they were about to split, another day they were about to be booked for the next gig, surviving between the call of the spirit and the ecstatic spill that daily life requires to move on.

William 'Buzzy' Linhart (1943-2020) had just finished his stint in the Navy when arrived in Miami around late 1963 to audition for a Tennessee Williams play. But his first night there, he went to the Unicorn (Coconut Grove) and he saw Fred Neil performing5. Linhart changed course right then and there and fell in love with the Crescent folk scene. It was the hootenanies' magic and open mic nights and the humble grace of Fred inviting him to play along (it was like that with other, later companions). Buzzy had already been playing drums and xylophone in the Navy, but he backed Fred on vibraphone. It would be difficult to find a better start than that. And everyone who speaks about Buzzy claims that he was a music enthusiast, continually hooked on creating.

Buzzy knew David Crosby and Mama Cass, who said to him that the next place he needed to go to start a music career was Greenwich Village in NYC. Linnhart probably went on Fred Neil's recommendation to John Sebastian's apartment in the middle of Greenwich Village, where Neil acolytes like Pete Childs and Felix Pappalardi already resided, as well as one Tim Hardin. John Sebastian described it this way: "Tim came into the Village in about 1963 or 1964. My house was one of his first stops, because I knew everybody he knew... Tim had heard my playing at Fred Neil's shows."6

By the fall of 1964, the Night Owl became the busiest place in the Village. The folksinger revival had reached its peak in 1963 and now the bands were taking the lead on the stages. Joe Boyd told it very graphically in his biography7. On the way back from one of his trips through Europe, he asked his colleague producer Paul Rothchild where to go, and Joe was led directly to the Night Owl, where Richie Havens, Tim Hardin and Fred Neil could be performing the same night, always backed up by exuberant bands. The three were pivotal in that moment in which folk music was absorbed by new foreign airs and mixed with other types of music. Their influence on many flourishing bands like The Lovin' Spoonful, The Youngbloods, The Seventh Sons and others who would rise to fame in the West Coast (like Buffalo Springfield and Jefferson Airplane) seems obvious but worth repeating.

Fred Neil had been "raga-ing" since he played more habitually in Coconut Grove around 1963, maybe before. Every time he returned to New York, he immersed himself beyond the folk, gospel and ragtime blues numbers for which he was more known. By late 1964, he had landed an outings at The Night Owl, along with Felix Pappalardi on bass or guitarron, Pete Childs on acoustic guitar, dobro or slide, John Sebastian on harp and Buzzy Linhart on vibes. Tim Hardin and Fred Neil, aside from playing guitar, electric and 12-string respectively, took turns on vocals or sang along. Though it is not known in detail, they were all on the same stage for a few weeks, some nights separated by interchangeable groups. Witnesses like photographer Michael Ochs8 and The Lovin' Spoonful bassist Steve Boone9 remembered these unannounced gigs as a breaking point in the scene. The improvised stampedes included instruments alien to American folk and jam sessions more similar to those at jazz clubs, and performing medleys with traditional material or original songs and spontaneous modal forms.

Hardin's love for the Chess label and especially a predilection for Willie Dixon inspired his "The Seventh Son" cover, which would be recorded by him in May 1964 (released on Tim Hardin 4) and undertaken live. Surely it had something to do with the name that would be given to an outfit that emerged partially from those gigs just then.

Steve DeNaut (1936-2005) had moved from Southern California to New York in 1956 to try out an acting career. He studied theater and performed in a variety of small shows. DeNaut describes his early days as such: "I hung out in the Village because that was where all the good looking girls were and that was where everything was happening... I hung out in the coffeehouses and learned to play a few folk songs on the guitar."10 Steve already knew Fred Neil before joining Linhart and Katzan: "I met Fred at the Gaslight- I'd heard about him for years, and we hit it off... When Fred Neil came to town, as he did every so often, it was a big deal. All of the folksingers wanted to see him. He asked me to play bass for him, and I was really excited."11 According to DeNaut, he replaced future Monkee Peter Tork on bass when started playing with Fred.

Around at the same time (about mid-late 1964), DeNaut ran into Buzzy on his first day in the Village. By then, the trio included Serge Katzan (drummer and percussionist who came from Baltimore jazz scene) as they played together initially. They jammed at a place they called (appropriately because the audience did not like it) the Boo Room, which was downstairs from The Couch coffeehouse. DeNaut: "We played with a saxophone player whose name I cannot remember. The tunes we played were Buzzy's "Yellow Cab" and a few more songs, so we played them over and over."12 The "Yellow Cab" song would be released by Linhart on his first solo album (Buzzy, Phillips, 1969) as an up-tempo Neil-esque blues, infused with certain ragtime impudence but combined with the "Hi-Heel Sneakers" beat that Tim Hardin used with his rhythm & blues numbers at the mid-1960's." According to DeNaut, the trio sounded like a blues group with some folk twist to it but they would keep blues patterns in tempo, and for this, they had Neil and Hardin supply unique input. Whatever they played at first, the line-up was not exactly going to be the most conventional in the Village folk circuit. With Buzzy on vibes during entire sets, or playing guitar during other sets, along with Serge Katzan on congas, tabla or drums, Steve DeNaut on electric bass and that ghostly sax player who would disappear quickly after two or three dates, they became The Buzz Linhart Trio.

It was an advanced folk-rock band, with doses of heavy blues as Buzzy played in an electric, and jazzier style than when he played on vibes, which was a huge advance from the former Trio. He was backing Richie Havens for a few nights at the Night Owl and in a trio with Pappalardi and Hardin. Vibes was an instrument alien to folk music until then. Around this early period of the Trio, Buzzy played vibes more than the guitar. In fact, he appears on vibes in two shows at different spots in which Fred Neil is backed by the Trio in 1965. Buzzy was progressively leaving the instrument once he took up the electric guitar but the vibraphone gave a jazzy feel to his folk-blues repertoire, twinkling the progressions and enveloping the songs until they were carried away. Hardin did not forget that sound because he would use the instrument on his first two self-titled albums, Tim Hardin 1 and Tim Hardin 2 (Verve/Forecast, both of them recorded between 1964 and 1966), albeit played by Phil Krauss and Gary Burton. This spacey and narcotic jazz-folk mode, with Mike Manieri on vibes, would have its peak on Tim Hardin 3 Live In Concert, his swan song and maybe his most charming album yet with Verve/Forecast (1968). As part of this drift, Tim Buckley learned the relevance of the jazz-vibed sonority, accompanied by David Friedman throughout 1968-1969 phase, live and in the studio.

Their first and only album cover photo

Soon the first write-up's about the former Linhart Trio came written by Robert Shelton (who had helped to popularize Bob Dylan early on) in The New York Times in 1964, writing that Buzz Linhart (not the trio) was "the first to successfully blend rock music and Indian raga." Buzzy had already listened to Fred Neil's broken-down and ragged gospel "Baby" in which Sebastian and Pappalardi backed him along with Vince Martin (Tear Down The Walls, Elektra, 1964), or heard him strumming until dawn, playing chain-gang numbers like "Linin' Track," "Rosie" or "Looks Like Rain," managing to turn them into vaporous and mystical sensations. Neil's relationship with Buzzy, as with Hardin, did not stop with the Trio gigs. Besides, in the wee hours in the Village, Buzzy had met exploratory steel guitarist Sandy Bull, who had recorded an instrumental Eastern and modal album for Vanguard Records, Fantasias For Guitar And Banjo, issued in 1963. Bull showed Linhart an open-tuned guitar in which raga could be played. Buzzy was always interested in Indian music since he heard Ravi Shankar and Bud Shank play together on a TV show in the early 1960's. Years back, Sandy Bull had met Hamza El Din in Rome: "I heard him play, and it blew me away. There was something very basic about it, the closest thing to simplicity you could get, with all this complexity within a very simple framework." 13 Another Eastern influence on Buzzy was (future Cream producer) Felix Pappalardi, who lived at Sebastian's apartment. By then, Felix was a respected session musician with Neil, Hardin, Richie Havens and Mimi & Richard Farina. He also was playing guitarron (Mexican bass) for bouzouki, keyboard and guitar player Steve Knight at a obscure Irish pub called Fenjoon, an exotic venue in McDougal Street that didn't last too long. Pappalardi could project the Turkish, Greek and Middle East scales in what would his first band, The Devil's Anvils, before founding Mountain. The same place would be other spring board for the Linhart Trio in its first months.

Eastern cultures were discovered by folk musicians because they were exposed to non-Western music, included at festivals and on record compilations they heard. In addition, there was an forward-looking mentality in folk-rock- a progressive push conditioned by fatigue or boredom of the stylistic patterns of the various branches of folk song that in many areas were identified with a reactionary rigidity. According to Country Joe & The Fish guitar player, Barry Melton, "a folk-rock idiom borrowing from jazz-ized folk music musicologically speaking... was logical at a time when Miles Davis and Doc Watson existed on the same plane."14

Many of those musicians introduced these types of accents and moods in North American folk music- as such, attributing it exclusively to one person or another would be unfair because other names and discordant data would surely appear. The truth is that these types of musical mash-ups happened before such things became popular, or even a fad, years later, during the psychedelic era. But The Linhart Trio "experience" remains pioneering, almost as early as the excursions by solo guitarists such as Sandy Bull or Robbie Basho, being perhaps the first to synthesize the Eastern influxes with the North American folk and blues, although with some relevant differences. First of all, the Sons were an ensemble and not soloists. What we might call John Fahey circle, in between Maryland, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, Berkeley and Cambridge, was, by then, in full flight, if most of the time scattered. Seekers of the roots of blues as well as renovators of forms were attached to tradition. Fahey, Basho, Bill Barth, Sam Firk, Max Ochs, Al Wilson, Henry Vestine (both of them Canned Heat founders later), producer and manager Ed Denson among others, also reached and touched the creative movement of the Trio via Max Ochs. Ochs would come into the band in late 1965, just when they started to be called The Seventh Sons. Ochs had already met Katzan in Annapolis some years before.

The Buzz Linhart Trio appeared late in the folk revival. Dylan had already taken of while many ex-folksingers and backing musicians got together, flowing into, on the one hand, electric bands booked by major labels, and on the other hand, into collectives and varied projects that amassed a rich and risked instrumental background and were tired of established musical structures. The Fugs' legendary member Tuli Kupferberg says it this way: "Just living in the bohemian atmosphere of Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side pushed you in a lot of free directions. ...You believed that the revolution was about to happen or could happen at any time soon, there was really no point in opting for a standard professional track."15 In many cases, the drift from social conventions was accompanied by a getaway from oneself, moving toward marginal, peripheral or subjugated cultures, usually including the blues. Joe Boyd provides some key thoughts about this revivalist folk-blues generation: "leaning towards a culture we sensed held clues for us about escaping the confines from our middle class upbringing." For Boyd, it was a real infatuation, the hypnotic quest to undertake came inspired by a ton of previous recording acts: "...artists appeared in our imaginations like disembodied spirits."16 Robert Cantwell wrote that the folk generation was "an intricate circulatory system of cultural ideas, independent of the official and visible system, through informal networks of people and communities to shape the collective experience, in which the imagination proved more powerful than either the sword or the dollar."17

"By the mid-1960's, the Village scene was going stronger than ever but something had been lost as well. More and more people were moving away," said the folksinger Dave Van Ronk18. It was a collective history, always about teams, communities and congregations, but in the mid-1960's, there was a detour. As Robbie Wolliver remembered, "(the) record business was a billion-dollar giant. Executives lavished money on groups that used to play for forty dollars a night in the Village."19 At that time, there was a music industry expectation about bands that forced them to fit into categories and easily recognizable styles. Many nascent blues-rock and folk-rock bands didn't last. The Seventh Sons came to treasure a kind of stern and precocious spirit. Maybe The Sons could have had the wisdom of not releasing their music until 1967, at the end of their days, when they were freed from achieving an impression that would limit them. It formed a thread to be explored in the second part of this article.

At this time in the mid 60's, bands, projects and collectives flourished with similar and irreverent idiosyncrasies. In NYC, for example, aside the Sons, The Fugs, The Holy Modal Rounders, The Insect Trust, The Godz and even The Velvet Underground started up as a folk oriented (and later a trash-core project) in the East Village. All of them appeared in the middle of the decade along with others from assorted cities whose paths intersected and would be part of larger currents. Deep in the ineffable, blues tradition, this music was expanded with forays the improvisational music, based on varied and exotic instruments and cultures and the immersion into music of Hindu and African cultures. Many of these artists made room in their sound to embrace emotional and spirited rhythms and exuberant harmonies scarcely found in American popular music. Nat Hentoff summarized the comprehensive vision of this spiritual searching: "The message of the new folk music can only be fully apprehended through the total medium - instrumental textures and ways of singing to construct instrumental colors and rhythms."20

But the mainstay of the gigs was "(Come Out And) Sing Joy," an old traditional song. DeNaut: "The song, other than the basic melody, was improvised and could last for only five minutes or as long as half an hour. It all depended on our mood or that of the audience. I think we were the only ones doing pretty out there for our time."21 The theme was recorded by Linhart on his Buzzy album (along with "Yellow Cab" and "Willie Jean"). We can get an idea about how this epic song sounded thanks to a 19 minute recording on that album. A brief chordal cadence floats underneath Linhart's musings, accompanied by acoustic guitar and percussion, with changing rhythms at various points. As he's hitting drone guitar points, or striking dissonant streams, Linhart is scatting throughout, letting out rapturous vocals up and down, as DeNaut said, depending on the mood.

In June and July 1965, The Buzz Linhart Trio backed Fred Neil at the Night Owl. Don Paulsen: "Fred was playing being backed by drums, bass and vibes. They made music that you couldn't believe. It was rock & roll and folk and country and jazz and blues all at once."22 The quartet played so much at the Night Owl that the late Joe Marra (owner of the venue, who recently passed away) became their unofficial manager during that year. DeNaut: "When the Buzzy Linhart Trio played with Fred, (we) always did his tunes. He was the leader and we followed his lead. We experimented with raga, with Fred on the 12-string, and had a ball with it... When Fred asked us to play with him, we jumped at the chance. While performing we could play a few of our own songs, but it was mostly the Fred Neil show and we were billed as (Fred with) the Buzz Linhart Trio."23

The track list, according to Paulsen24, included Fred's songs like "That's The Bag I'm In," "Gone Again," "Blues On The Ceiling," "Look Over Yonder" and "Other Side Of This Life." Buzzy: "Fred liked to take this one note and hold it, mess with the beat, and let somebody else solo, and I knew which notes you had to use to simulate the tension you would need in a one-chord song like East Indian raga was. I felt it was amalgamating different forms so you could put country together with jazz, and generally that's against the rules. You weren't supposed to do that."25

In order to rehearse and to celebrate their passion for the music, The Buzzy Linhart Trio used to play jam-sessions up at drummer Serge's loft in the Lower East Side. There were long improvisations played for the sake of the amusement of Linhart, Katzan, DeNaut and Ochs, attended by supporters and musicians close to the band like guitarist Ned Carter (who had backed Fred Neil in the Grove), Barry Goldberg (Dylan's piano sideman at the Newport 1965 Fest), Lee Cabtree (The Fugs' usual arranger and keyboardist and Pearls Before Swine early session musician). There were also more renowned players like Donovan, along with his former collaborator on sitar, 12-string guitar Shawn Phillips (formerly himself performing as soloist at the Cafe au Go Go after a long stint in London), Jerry Garcia (Grateful Dead), David Crosby (The Byrds), David Blue, Jesse Colin Young (The Youngbloods), Richie Havens, Gram Parsons, The Chamber Brothers, and master bluesmen Mississippi John Hurt and Skip James among other people. According to DeNaut, these jams were partially taped on reel to reel tapes and still exist, owned now by Katzan's daughter. Buzzy Linhart's official webpage provided some info about these (or other possible) recordings by the band. It seems incredible that after having played with such a roster of magnificent names, The Seventh Sons still are a secret to be discovered.

1) Eric Von Schmidt & Jim Rooney: Let Me Follow You Down: Illustrated Story of the Cambridge Folk Years: The Illustrated Story of the Cambridge Folk Years, University Massachusetts Press, 1994.

2) Goldmine magazine, #411, April 26, 1996.

3) Richie Unterberger: Urban Spacemen And Wayfaring Strangers, Miller Freeman, 2000.

4) Don Snowden & Willie Dixon: I Am the Blues: The Willie Dixon Story, Hachette Books, 1990.

5) Ben Edmonds "I Didn't Hear A Word They Were Saying", Mojo magazine, February 2000.

6) Robbie Woliver & Martin Fitzpatrick: Hoot!: A Twenty-Five Year History of the Greenwich Village Music Scene, St. Martin Press, 1994

7) Joe Boyd: White Bicycles, Serpent's Tail, 2006.

8) Jac Holzman & Gavan Daws: Follow the Music: The Life and High Times of Elektra Records in the Great Years of American Pop Culture, First Media, 1998.

9) Richie Unterberger: Turn! Turn! Turn!: The '60s Folk-Rock Revolution, (Backbeat, 2002).

10 / 11) Interview with the author.

12) The Seventh Sons, Green Groceries, 2nd issue, Rotterdam, 2002.

13) www.globalvillageidiot.net/bull.htm

14) Richie Unterberger: Eight Miles High: Folk-Rock's Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock, Backbeat, 2003.

15) Richie Unterberger: Urban Spacemen And Wayfaring Strangers, Miller Freeman, 2000.

16) Joe Boyd: White Bicycles, Serpent's Tail, 2006.

17) Robert Cantwell: When We Were Good: The Folk Revival, Harvard University Press, 1996.

18) Dave Van Ronk: The Major Of McDougal Street, Da Capo Press, 2005.

19) Robbie Woliver: Hoot!: A Twenty-Five Year History of the Greenwich Village Music Scene, St. Martin Press, 1994.

20) David A. Turk: The American Folk Scene: Dimensions of the Folksong Revival, Dell Publishing, New York, 1967

21) The Seventh Sons, Green Groceries, 2nd issue, Rotterdam, 2002.

22) "Where Is It All Going," Hit Parader, January 1966

23) Interview with the author.

24) "Where Is It All Going," Hit Parader, January 1966.

25) Peter Neff: That's The Bag I'm In. The Life, Music And Mystery Of Fred Neil, Blue Ceiling, 2019.

The Buzz Linhart Trio's jazz, Eastern and folk-rock variations along with drones and ragas were being introduced to New York music stages, mostly with Western instruments. They played The Night Owl in the spring of 1965 when The Lovin' Spoonful were substituted there otherwise during various weeks. The bills also included new psych & blues bands like The Myddle Class, The Blues Magoos and The Strangers. Woody Kamm, a member of the latter, remembered how The Trio taught him a fave folk-blues standard like "Get Together" by Dino Valenti, later popularized by Jesse Colin Young's The Youngbloods. Other songs of the Trio's repertoire were "Yellow Cab" and "A Tear Outweighs A Smile," both by Buzzy with the latter one as of the Linhart's hard-blues, plus a slowly cool and catchy "Willie Jean" (by actor and folksinger Ben Carruthers), "That's The Bag I'm In" by Neil and "Reputation" by Tim Hardin (these last two soon would feed Gram Parsons' early repertoire, and would influence him to found The International Submarine Band later).

FOOTNOTES