TRINI LOPEZ

My Name Is Lopez: a revealing bio pic

by Richie Unterberger

(August 2022)

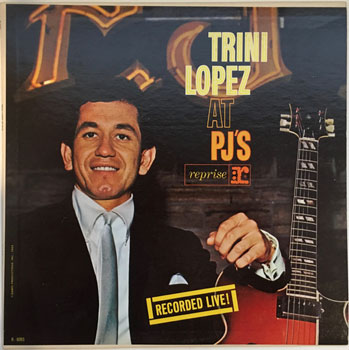

On the surface, Trini Lopez can epitomize '60's pop at its most congenial and happy-go-lucky. He's the guy who made folk swing, or even into a sort of go-go party music, with his Top Five 1963 live LP At PJ's. He took "If I Had a Hammer" even higher in the charts than Peter, Paul & Mary did, and brought the same peppy cheer to standards like "Down By the Riverside," "La Bamba" and "This Land Is Your Land," mixing in some rock'n'roll, R&B, and Broadway.

"The only thing I didn't change was the lyrics," he laughed as he told me how he gave folk a new slant when I interviewed him twenty years ago. "But I changed the music completely. Everybody calls it the Trini Beat. They were dancing to my songs all over the world at discotheques."

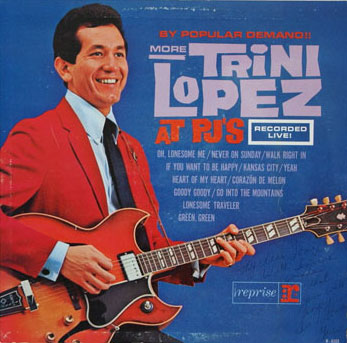

Yet behind the nonstop party captured on At PJ's, and his almost equally successful follow-up More Trini Lopez At PJ's, lay a long struggle to establish a musical identity. Despite his hits' incessant mirth, he had to overcome a lot of racism along the way, at a time when Latinx celebrities were far fewer in number, and prejudice much more rampant. He beat those barriers to get signed by Frank Sinatra's label, become pals with Sinatra himself, and share a bill with the Beatles just as "I Want to Hold Your Hand" was soaring toward #1 in the US. He might have had the acting career Sinatra had as well, if not for some perhaps ill-considered advice from Frank himself.

The new documentary My Name Is Lopez, directed by P. David Ebersole and Todd Hughes, uncovers a more complex story behind the singer than many listeners would suspect. And it uncovers more vintage performance footage from anyone but the most diehard Lopez collector would suspect existed, from several rocking '60's renditions of "If I Had a Hammer" and his cameo of "Sinner Man" in the 1965 film Marriage on the Rocks to unlikely collaborations with Chuck Berry, the Everly Brothers, Lesley Gore, Vikki Carr, and even Soupy Sales. He guested on shows by Andy Williams, Johnny Carson, Dean Martin and Hugh Hefner. He performed in Japan, Europe, and Australia. When he shared a bill with the Beatles in Paris, his drummer was Mickey Jones, who'd drum with Bob Dylan and the future members of the Band on Dylan's famous 1966 world tour.

"There was a certain moment where he had been a household name," says Ebersole. "Everybody knew who he was. He was on TV all the time. He was in your living room, and you knew the name Trini Lopez. Then there's a certain point when that became not true. That's what happened to a lot of artists. They have their moment, and do they get carried forward by 'history'?

"In Trini's case, it's part of why we wanted to make the film. We felt he deserves to have been carried forward. So we hope there's an opportunity to build a rediscover, or remember."

The Long and Twisting Road to Hollywood

Trini's father, like the ancestors of many Mexican-Americans, traveled back and forth over the Rio Grande before he and Lopez's mother settled in Texas, where the singer was born in 1937. Growing up as a Mexican-American in Dallas had its challenges in the middle of the twentieth century. Lopez and his family sometimes put in sixteen-hour days as migrant laborers. Time off for work meant that Trini didn't graduate middle school until he was seventeen, and didn't finish high school when he needed to help the family out by taking odd jobs.

There was also the everyday racism that many people of color faced. "It kind of makes you feel almost dumb to say this is a surprise," observes Ebersole, "but when Trini said 'we had to ride in the back of the bus like the blacks'... As Americans we go, 'oh, of course that's true,' but we didn't really think about it. We get taught the history of blacks had to ride in the back of the bus. So I think when people see the story and see what it was for a Latino family trying to break through in America at that time, they didn't necessarily know and realize that the struggle was similar. That's been one of the things that is a big takeaway when people see the movie."

Although Lopez died in 2020, fortunately, the directors were able to interview him extensively for the movie shortly before his death, as well as film a low-key 2019 Palm Springs club show where Trini mixed music and stories. While his rugged upbringing and the steely resolve he called upon to slog through years of flop singles and other roadblocks isn't reflected in his consistently easygoing demeanor, certainly it left a mark that remained vivid in his memories more than sixty years later. Particularly, the racism that came not just from the places you might expect, but also from within the burgeoning rock'n'roll business itself.

"Buddy Holly's aunt was a teacher at Trini Lopez's high school," says Hughes. "She said, 'you've got to meet my nephew,' 'cause Trini was a big musical headliner at his high school." In the late '50's Holly, already a Texas rock legend, introduced Lopez to his producer, Norman Petty. Trini's band subsequently traveled to Clovis, New Mexico--the small town where Petty had his studio--to do some recording.

Trini had been the group's lead vocalist, but the non-Latinos in the band didn't let him sing at the session. "We say in the film, it was [the producer's] suggestion," adds Hughes. "'You don't want this brown guy leading these guys.'" After three days of instrumentals, he quit to form another band, although the group had a deal with Columbia Records.

"Of course, it is a racist moment," feels Ebersole. "But it was also the times, the record industry saying, 'Well, this isn't done. Sure, the kid's talented, but how are you guys gonna get a career [with Trini] up front?' That's I think where Trini's underlying belief in himself came through. He was the one who was saying, 'Well, if that's the case, thanks but no thanks. And I'm off. Right? I'll have to find myself another band.'

"It wasn't like, 'Oh, okay, well I'm devastated, and now I just won't sing, or I won't do anything.' That's where I think he is a hero, a trailblazer. He didn't accept what it was they were saying he had to accept."

The rejection's especially ironic considering Lopez was recommended by Holly, who'd marry a Latina, Maria Elena Santiago, the year before his death. To Ebersole, it illustrates "how natural it was for Buddy Holly to not be racist. Whatever it was that was in his makeup, where he was like 'well, I'm in love with this woman. I don't care what the culture says and what society is. Oh, Trini's really cool and he's great at music. I don't care what everybody else says.'"

After the disappointing Clovis sessions, Lopez was able to release a debut solo disc for the small Dallas label Volk, with a catch. They wanted to Anglicize his name to something not identifiably Latino. Trini held his ground and insisted it come out billed to Trini Lopez. "The Right to Rock" (on which he was co-credited as songwriter), unlike his well-known '60's recordings for Reprise, was straight rock'n'roll with a hint of Tex-Mex, as most of his singles would be in the late 1950's and early 1960's. It's arguably the best of his pre-Reprise efforts, and although it doesn't specifically lobby for social justice, it asserts the right to rock as given by the Constitution, Bill of Rights, and the golden rule. Although it hasn't been easy to find on reissues, it was recently used as the title track for Bear Family's early Latinx rock compilation The Right to Rock: The Mexicano and Chicano Rock'n'Roll Rebellion 1955-1963.

Of course, many celebrities past and present have changed their name, and often de-ethnicized it, from Bob Dylan on down. Hughes finds Lopez's refusal to fall in that line significant, and thinks the film was made at "a perfect time, because we've become so aware of systemic racism, to understand how difficult it was for him. And that he really changed the course of history by refusing to Anglicize his name. He was the first one. After that, other people had the confidence to see that a Lopez or Rodriguez could be on a marquee, could sell records. People would not stay away because of his name."

They weren't, however, flocking to buy his singles the first years of his career, although most of them appeared on one of the biggest independent labels of the era. Based in Cincinnati, King Records had scored many hillbilly and hits starting in the mid-1940's, and was also home to soul superstar James Brown, as well as blues great Freddie King. But Lopez's King singles, now available on the Ace collection Sinner Not a Saint: The Complete King and DRA Recordings 1959-1961, tended toward rather generic period rock'n'roll of the doo wop and mild rockabilly varieties.

There were some bright spots during these formative years. He got some local chart action in Dallas. "It Hurts to Be In Love" would be covered by labelmate Freddie King and, through that route, make its way to John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, whose live 1966 version (with Eric Clapton on guitar and Jack Bruce on bass) would eventually get issued on Primal Solos. "The Search Goes On," one of the few King sides for which he had a songwriting credit, has a nice dark rockabilly feel. As another historical footnote, his 1962 single for the DRA label, "Sinner Not a Saint," was written by Shel Talmy, who'd soon move to London and produce the first explosive hits by the Kinks and the Who.

Lopez could have been a historical footnote himself if not for another Buddy Holly connection. Since Holly's death in February 1959, his band the Crickets had continued with different lead singers. Trini had a chance to join the band in that role, though it meant taking the chance to move to Hollywood, where he drove to hook up with the Crickets.

Live at PJ's

Hollywood would indeed give Trini his big break, but not the one he'd driven out in hopes of getting. The gig with the Crickets didn't materialize, but he started to gain a following fronting a trio with other musicians. One of them was drummer Mickey Jones, who'd first played with Lopez back in Dallas. Their shows at the Hollywood club PJ's brought them to the attention of Frank Sinatra's label, Reprise. By then, Trini had taken long strides toward a more identifiable style that was only hinted at by the wealth of tracks he'd cut for King and other companies before hitting Hollywood.

As Lopez put it when I interviewed him in 2001, when he was with King, "I was the only Latino at the studio. I was doing my thing with my guitar, but it was camouflaged by their sound. But when I started recording on my own, with my own guys, then it clicked because I had my own complete sound."

Part of the revamp inserted folk songs into his repertoire, at a time when the commercial folk boom was peaking. "Folk music was very in. I liked the melodies, I liked the lyrics. But I didn't do 'em the way they were being written. I did 'em my way. I changed them around for my own satisfaction, my feeling of the songs. The only thing I didn't change was the lyrics," he laughed during our conversation. "But I changed the music completely." Not just on folk songs like "This Land Is Your Land," but also classics from the soul ("What'd I Say"), Broadway (West Side Story's "A-Me-Ri-Ca"), and Latin ("La Bamba") worlds, all of which he'd place on his debut LP.

When Lopez was interviewed nearly twenty years later for the documentary, relays Ebersole, Trini remembered that when Reprise "wanted him to record, they wanted him to do it live. He was like, 'Why don't we go in the studio like everybody else?' [Producer] Don Costa, must have said, 'But when he performs live, he's like himself. And it's wild, and it's turning the kids on.' And he was just more free.

"I think because it was live, he was fully being himself. Whereas when you go in to the studio they start to shape you, and say 'maybe sound like this, maybe sound like that.'" In Ebersole's eyes, that was definitely the way to go, as a studio set "wouldn't capture that magic. But when he was in front of that live audience he could respond back and forth, which was true to the end. When Trini got up in front of a live audience, there was just magic between the two of them, the audience and Trini."

Recorded on his home turf with an enthusiastic live audience, Live at PJ's hit the Top Five, catching a big tailwind from his hit treatment of "If I Had a Hammer," which had gone to #3 a few months earlier. Peter, Paul & Mary had taken the tune--written by Lee Hays and Pete Seeger of folk giants the Weavers, whose original version came out in 1950--into the Top Ten almost a year earlier. That's where Lopez first became aware of the song, and as he told me, he cut it at PJ's since "because I liked the message it had, and liked the melody. And of course, I just changed the whole thing around. I made it not only listenable, but I also made it danceable."

As unlikely as it seems when history has usually cast the Byrds, Bob Dylan, and others as the originators of folk-rock, his arrangement of "If I Had a Hammer" might have also foreshadowed folk-rock in some ways. Jefferson Airplane founder Marty Balin cited Trini's use of electric instruments on folk songs as part of his inspiration for pursuing folk-rock. Not only did Lopez play electric guitar on the song; he was also, of course, backed by drummer Mickey Jones, about three years before Jones would play with Dylan.

Perhaps the best clip of Lopez in performance--seen in full on the three-DVD set The Best of Hootenanny--shows him playing "If I Had a Hammer" with zest on electric guitar, and a rather nonchalant Jones on drums, in late 1963. With numbers like these bunched together in a fast-paced live recording, asserted Lopez in our interview, listeners all over the globe "would put the album from side A to side B, and then side B to the other side, and play it all the way through."

Shortly after that Hootenanny broadcast, Lopez would take one of his first major steps toward bringing that music to the world with a multi-week gig at one of Europe's most storied venues. There he'd intersect with the band that would soon take their music to the United States, changing the world in the process.

With the Beatles

Only about ten days after At PJ's peaked at #5 in the Billboard charts, Lopez began a three-week series of concerts at the prestigious Olympia concert hall in Paris, sharing the bill with two other stars. One, Sylvie Vartan, was a big name in France, and never cracked the English-speaking market, though she actually recorded quite a bit in the language in the 1960's, even cutting an LP in Nashville in late 1963. The other act was almost as unknown in the US as Vartan in late 1963. By the time the Olympia shows started, that had changed.

The third act, of course, was the Beatles, just weeks before their first American visit. Although accounts of their Olympia residency vary, certainly they didn't send Parisian audiences into as much of a frenzy as they were doing back home, or would soon do in the States. According to one report from the time shown in My Name Is Lopez, Trini was called back for seven encores while the Beatles got only two. Not that the Beatles were bothered; "I Want to Hold Your Hand" was skyrocketing to #1 on Billboard while they were in Paris, just weeks ahead of their first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show.

No one was going to be more popular than the Beatles in the years ahead, but Lopez was certainly holding his own in European markets even before the British Invasion started. "If I Had a Hammer" made the UK Top Five in fall 1963 even as Beatlemania exploded in Britain, and At PJ's actually made the UK Top Ten just two days before it did in the US. Interviewed about the Beatles just before they flew to New York in February 1964 for their first US visit in an archive clip seen in the documentary, Lopez was gracious and charitable. "I hope they'll have success in America, because they're very nice boys," he told the interviewer. "They're very, very nice human beings. And they've got great talent."

About 55 years later in My Name Is Lopez, Trini offered more specific and colorful memories. On one occasion when he was interviewed at the Olympia, he remembered, "In my dressing room...the walls were very thin... They said, 'do you think the Beatles will be a success when they come to New York?' And I said, 'well, I gotta tell you the truth.' I had to whisper, because I could hear everything they used to say in their dressing room. I'm sure they used to hear me. So I said, 'I don't think so. In America, there is a group that I like much better than them called the Beach Boys.'"

While some viewers might find this a putdown, if a gentle one, of the Fab Four, the filmmakers see it in a different light. "I think he's also kind of taking the piss out of himself by saying, so here I am," is Ebersole's take. "I'm getting to hear them before everybody else heard them, and I didn't get it. It was just before they came over, and everyone went insane for them. I think he's sort of making a joke on himself, that 'I wasn't smart enough to see it.'"

Lopez wouldn't match the chart success of the Beatles in the US and UK, or even match the heights he'd scaled with "If I Had a Hammer." There was just one more Top Twenty single, "Lemon Tree," though he had a dozen other Top 100 entries. A half-dozen other Lopez LP's would make the Top Forty through mid-1965 (including the live follow-up to his debut, More Trini Lopez at PJ's), but no other longplayers would afterward. Billboard's American chart listings don't tell the whole story however, as Lopez gained and sustained a huge overseas audience. Some of his singles were much bigger hits in other countries like Belgium and Germany, their chart positions noted with on-screen sidebars as the songs play in the new film.

"We can get so US-centric about our presentation of artists," says Ebersole. "But an artist like Trini was international, and remained international all the way through his later years. In some ways he was actually more known internationally than he was here in his later years. He continued to get requests from Germany to play, and the Netherlands. So it was part of what we wanted to make people aware about him as well. Yes, you kind of can become a famous artist by doing well in the United States. But also, there's a big world out there. We often forget it as Americans."

And Lopez continued to pop up on all manner of TV shows years past his commercial prime, even rendering Johnny Carson speechless in 1973 by having him sample a jar of burning-hot jalapenos. Besides some unlikely duets mentioned earlier, there were unlikely songs, like "Light My Fire" and "Land of a Thousand Dances"; a range that could stretch from slots on teen-targeted rock shows like Hullabaloo to variety mainstays Bob Hope, Ed Sullivan, and Carol Burnett; and a spot on Playboy After Dark. All of this is seen in My Name Is Lopez, featuring rare footage tracked down with help from huge Lopez fan Bob Furmanek, president and founder of the 3-D Film Archive. Hughes gives one example: "He had a 16 millimeter print of a concert [Lopez] had done in Tokyo that was never on TV or anything. That's where we got a lot of the cool dance moves from."

Still, as the mid-'60's passed Trini's sales were undeniably slipping. Surpassing him on the charts was Johnny Rivers, whose more rock-and-soul-oriented brand of club-a-go-go bore some similarities to Lopez's. Rivers "used to come see at PJ's all the time, and then he went as far as to take Mickey Jones away from me," Lopez noted in his interview with me. "He paid him more money, and Mickey went with him."

In keeping with his magnanimous bearing, Trini was far more gracious than bitter, adding, "After I left PJ's, the minute I hit big, I had to go on with my life. I went from $250 a week to $10,000 a night the minute I left PJ's. So Johnny came in with Mickey, and he did 'La Bamba' and all those songs. I used to get calls from people: 'Trini, we got Johnny Rivers trying to do you and we think he is a poor man's Trini Lopez.' People used to tell me that all the time. But he's very talented."

Lopez could have gone on making a good living indefinitely as an internationally popular act, particularly on stage. Around this time, however, he got the opportunity to branch out into film stardom. He took it, though it didn't work out quite as well as he might have wished.

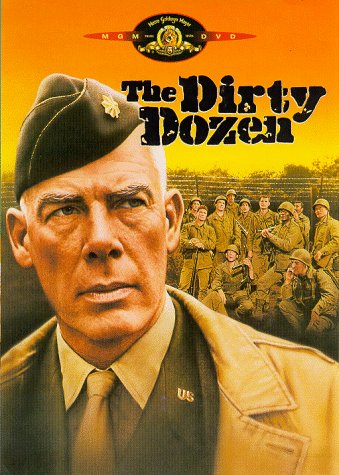

The Dirty Dozen and Its Fallout

Trini landed a notable supporting role in the 1967 hit film The Dirty Dozen, albeit in the midst of, as the title itself announced, a pretty large cast. He played one of a dozen criminals of various ethnicities serving (in his case) long sentences or (in others) on death row who were enlisted for a dangerous, even suicidal pre-D-Day World War II mission. The all-star cast included Ernest Borgnine, Lee Marvin, George Kennedy, John Cassavetes, Telly Savalas, Charles Bronson, and a young Donald Sutherland. There was also another celebrity, football player Jim Brown, who was moving into acting after establishing himself as a star in a different field.

Although Lopez acquitted himself well in the role, it could have been significantly larger. When filming ran a few months over schedule in England, Trini was advised by his friend Frank Sinatra to leave the production. When he did, much to the displeasure of director Robert Aldrich, his character was killed off prematurely in the final movie. Some feel his movie career was prematurely killed off as a consequence.

"He said, I think you should leave the movie, "Lopez explains in the documentary. "Because your career right now, you're as hot as a firecracker," though he'd cooled off considerably chart-wise by 1966. "And if you don't go back to your playing and touring, they'll forget about you. I said 'oh, okay.' He got three attorneys to get me off the movie."

"I think without a doubt he would have been a major movie star, had he stayed in," Hughes speculates. "Because everyone was talking about him being nominated for an Oscar. He had a very pivotal role."

Continues Ebersole," The last part of the film, there's the guy whose foot gets stuck in the roof. You sort of wonder why it happens this way when you watch the movie now. But that was supposed to be Trini. Then he was supposed to be the one who throws the grenade in, and has the hero's role of sacrificing himself to stop the Nazis.

"His part did get minimized because Robert Aldrich was so mad at him for leaving the movie. That would have been his big moment. I think that's why people were saying, he could have gotten nominated for an Oscar for that supporting role"--though, in fairness, Cassavetes (who did get an Oscar nomination) and Bronson had considerably larger supporting roles, and Lopez's would still have been considerably smaller than theirs had he been able to do that scene.

(As a side note, the guy who did sacrifice himself from the roof in the film, Ben Carruthers, was also a singer, though his recording career was brief. His 1965 single "Jack O'Diamonds" (a Bob Dylan poem set to music, with the Deep), however, was notable for being produced by Shel Talmy and getting covered on Fairport Convention's first album.)

A couple somewhat different perspectives, incidentally, are heard from other members of the cast in the commentary track on a 2006 DVD release of The Dirty Dozen. "Trini was the most popular guy, because he had this song out, 'Lemon Tree,' and he was a singer," remembered Jim Brown in that commentary. "So everybody knew him better than they knew anybody else. So he was very popular, and he was a friend of Sinatra. But I think now Sinatra told him that he should tell Bob [director Aldrich] that Bob should expand his role, because he was a big star and everybody loved him. So he foolishly, I guess, told Aldrich that he wanted his role expanded.

"So... He was out of the movie. Then he had another actor take his part, over what he would do up on the roof of the castle... In one day, he was gone."

Adds Donald Sutherland in the same commentary, "So he came back to Bob Aldrich and said 'I'm off, I'm gone, I'm finished. You've gone over your time, I'm done.' Trini came to the screening that night [after the scene was rewritten], even though he was gone. And he looked at the picture and he said, 'Oh shit. Mr. Aldrich, I would like to come back and play this and finish the role'. And Bob Aldrich said, 'You're hanging on a tree, Trini. You're outta here.'"

Lopez did later act in some TV shows and obscure movies, playing, for instance, opposite Larry Hagman in the forgotten 1973 Chile-set flick Antonio. But according to Hughes, when Trini left The Dirty Dozen, "It was spun that it was Trini's being difficult. So he didn't work. No one would hire him."

Lopez doesn't seem regretful about that loss of work, or indeed anything, in his interviews for the documentary. However, Ebersole detected at the very least some mixed feelings about the episode. "Trini is one of those people that trying to have no regrets, he says, 'Look, it happened the way it was supposed to happen, and it was what it was.' But when he talked about [it], he was pretty wistful. He knows that that was a moment. He knows that he made a choice there, or allowed Sinatra to sway him in a choice. 'Frank was good to me. What was I supposed to do?'"

There were, it should be emphasized, some major advantages to his close association with Sinatra, whose Reprise label had been crucial to launching Lopez to stardom. Trini also became something of a satellite member of the Rat Pack, which might have helped him break ground as an early Latino star to play Las Vegas. At the same time, as Hughes points out, "Trini was making him money"--money that could have been lost if his recording career was interrupted or curtailed by film stardom. "And Trini was like, 'it's Frank Sinatra. I have to do it.'"

Although Lopez wouldn't even dent the Billboard Top 100 with singles after early 1968, he kept recording for Reprise until the beginning of the 1970's. He put out more singles for the label than even some major Lopez fans might be have heard. The recent Omnivore anthology The Rare Reprise Singles has a couple dozen non-LP tracks spanning 1962-70, including a studio version of "A-Me-Ri-Ca" (a live performance of which had led off At PJ's); a song he performed in The Dirty Dozen, "The Bramble Bush"; and covers of Randy Newman's "Love Story" (produced by Bob Gaudio of the Four Seasons) and the Vogues' hit "Five O'Clock World."

He subsequently recorded for a few other labels, and live and TV work continued. Twiggy even introduces him in a 1981 clip in My Name Is Lopez. But as Lopez himself told me in 2001, "I've been kind of retired since 1981."

How did Trini feel about the times passing him by? "I think the biggest frustration about it was that music changed, and it kind of felt like what he did was not what was selling, and what people were interested in anymore," says Ebersole. "I think it was the times. I think he just kind of trended out. We always say he kind of outlived his own thing." Although, as Hughes notes, "He was always a thing in the Coachella Valley. He's played for the last twenty years all over, and everyone has a story about him and everyone's seen him perform."

Making My Name Is Lopez

Ebersole and Hughes originally intended to pursue more interviews for their documentary, including Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Nancy Sinatra, and Reprise Records executive Mo Ostin. The pandemic, however, made it hard, as Ebersole says, "to get anybody at that point to agree to even be willing to having me send a cameraman to their house. So what we decided was--and the title of the film to some extent speaks to it--let's focus on letting Trini tell his own story. Instead of doing a million talking heads and all sorts of record execs, or radio people or this or that, let's let Trini tell us what happened."

Interviews with a few other figures dot the film, including Dionne Warwick (while she was interviewed by the directors for their documentary about Pierre Cardin), The Dirty Dozen co-star Jim Brown, and Tony Orlando, who as Hughes reports "we pursued doggedly because he was the one who said, because of Trini, all Latino people could use their name." Less expectedly, Dave Grohl and Ride/Oasis guitarist Andy Bell also briefly appear, extolling the virtues of guitars Lopez used. Also getting time is Trini's longtime companion Oralee Walker, who collaborated with Lopez on an as yet unpublished biography of the singer.

But much of the narrative is driven by interviews with Lopez in his Palm Springs home, as well as excerpts from stories he told during the concert that was filmed for the movie. "To know Trini is to listen to Trini's stories," says Ebersole. "He likes to tell the stories of his life, and what he went through, and his house was covered with his memorabilia. So he lived with kind of the history of his life and his career. If you're at his house and go 'oh, what's that, that's a cool picture,' he'll tell you the whole story behind it. It's kind of part and parcel of who he is. He kind of lived with all those memories. So to kind of get it all out at once and put it into one body of work was something he was really trying to make happen. I think it's why he was writing the book right at the same time."

Unfortunately, the pandemic would claim Lopez's life before the film was completed. "I don't know that I believe that he had a feeling he was towards the end, because I don't think any of us thought Trini was going anywhere. He was fully healthy. He went into the hospital for old man problems, kind of took care of what his issue was, came home, and was sick. So we think that he somehow, in the process of being transferred and being in contact with all those people at the height of COVID, just accidentally caught it. But that's when he got really weak. It was in that next week between getting home from his normal procedure to the following week," Lopez dying on August 11, 2020. "I don't think he was like, 'Oh, this is the end for me, I really want to get my story out.' I think he just enjoyed telling his story."

The story was told more fully on camera after Trini's passing. "I will say, the movie changed considerably after he died," remarks Hughes. "He never said 'don't interview Oralee,' but she never came up as being an interview subject. We did interview her after he died, and we were able to address the racism and be a little more critical of people. I don't think he would have liked us saying anything about Sinatra. He was just so grateful, even though he couldn't call him Frank. He was still like, 'Well, he gave me the opportunity.' So we were able to be a little more critical of how he was treated."

Ebersole agrees. "She's there when the cameras are not on, so she's talking to Trini, and does know how he feels. So when she's really representing his feelings so stridently in that sequence, you know that she's not making that up. Trini is the kind of person who publicly would never say a bad word about Sinatra or anybody. But privately, I think that he had a lot of regrets about it. Oralee gives us that window."

While the film has only had limited screenings before its planned spring 2022 theatrical release, Hughes is heartened that "we're finding the Latin audience, which is great. I'm finding there's a much bigger history of Latino rock in America. History kind of ignores them. So it's been great to reignite that pride, and that history."

In Los Angeles, Ebersole chips in by way of illustration, "We did a screening at the Grammy museum, that was kind of our L.A. premier screening of the film. There was a young Latino couple in the audience. The girl had seen the ad for it and knew who [Lopez] was, and brought along her boyfriend. He was like, 'I knew nothing about any of this. I'm so happy she made me come today.' We need to know these stories. That feels great, when those moments happen.

"The Grammy museum, after having seen our film, decided to do a full-floor exhibition celebrating Trini. He was a 1963 best new artist Grammy nominee, so once they saw our movie, they were like, 'We should do a tribute to him.' The same time as the movie will come out in April, the Grammy museum is also dedicating a floor. It'll run through September."

None of this would have happened had Lopez's family not been able to move from Mexico to Texas, reminding us of the contributions such immigrants have made even as immigration continues to be a major controversial political issue almost a century later. "When you look at.... how could it be that we might not have had that music? It's horrible," exclaims Ebersole.

"It's not a negative that we have, through our history as the United States, allowed people in and had this melting pot of cultures that adds to our identity and who we are. It is literally part and parcel of what the country is. We have these concerted tides every now and then that suddenly want to lock everybody out, or bring back a kind of white supremacist kind of attitude to the country. It's anathema to who we are as a people. We think it's a major point that we are made up of these cultural heritages that enrich us. So Trini's just a great representative of it."

And see Richie Unterberger's website