Twentieth-Century Flute Music

A Vintage Album for the Adventurous

By Kurt Wildermuth

(February 2023)

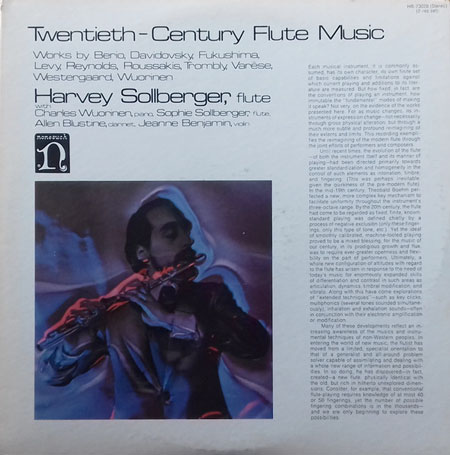

Welcome, adventurous listener, or flute lover, or both! Should you continue past this sentence, you'll read about Twentieth-Century Flute Music, a two-LP set by the flutist Harvey Sollberger and collaborators, released by Nonesuch Records in 1975. You will not encounter overviews of twentieth-century music, flute music, contemporary classical, electronic, or any other category this record might fit into. Nor, for that matter, will you find a musicological analysis by an expert in any of these genres.

No, as the title and subtitle of this piece signpost, you will encounter herein a look at a recorded-music analog artifact from the perspective of a record collector who happens to be an open-minded listener. Along the way you will experience advocacy for the flute as a solo expressive instrument and for this album in particular, but these initiatives will issue from a strictly amateur perspective.

First things first: the flute. The poor, underappreciated flute! If you can't stand the flute or seldom pay attention to it, what are you doing here? But since you're here, think back to flute music you might have enjoyed at some point. For some of you, those who really need convincing, that might mean band practice in elementary school; think beyond that.

The flute has been part of orchestral music, of course, whether purely instrumental, as backup for vocals, or as part of a mix. However, for the sake of this piece, focus on flute solos. Take your time.

If you are a rock music fan, the first name that may come to mind is Jethro Tull. This name of course refers to a band that, since 1968 and through numerous personnel changes, has been led by the singer, songwriter, guitarist, and flutist Ian Anderson. Nothing on Twentieth-Century Flute Music sounds remotely like Jethro Tull, and Anderson's playing tends to be far more breathy than Harvey Sollberger's highly controlled work here. Still, in their quieter moments, Anderson's more freewheeling and extended solos, such as on the 1978 album Live--Bursting Out, present not-bad starting points for understanding the flute playing on Twentieth-Century Flute Music.

If you are a jazz fan, you may be thinking of Herbie Mann. In a career that stretched from the mid-fifties to his death in 2003, Mann explored countless styles, playing flute and tenor sax and clarinet--not simultaneously--in bop, samba, fusion, salsa, reggae, disco, and more. His albums At the Village Gate (1962) and Memphis Underground (1968, and featuring the guitarist Sonny Sharrock, now remembered as a player of great fire) are particularly worth checking out. Stone Flute (1970), in its meditative calmness and ambient use of sonic space, could be a hipster precursor to Twentieth-Century Flute Music.

If you are a classical music fan, a Celtic music fan, or just culturally aware, perhaps the flutist James Galway comes to mind. The Irish-born Sir James Galway OBE has performed for some sixty years as an orchestra member and a soloist. His recordings favor older classical music and popular contemporary tunes, but there may be sonic connections to Twentieth-Century Flute Music on 1975's Sonatas for Flute and Piano (with Martha Argerich) or 1982's Galway Plays Mayer: Sri Krishna / Flute Concerto: Mandala Ki Raga Sangeet.

Interesting that Ian Anderson, Herbie Mann, and James Galway are men, when people often associate the flute with women. Surely there are women whose flute playing deserves more prominence! Web searches indicate that flutists such as Bobbi Humphrey and Hilary du Pré are worth investigating.

Meanwhile, just so you know where I'm coming from: Until I acquired Twentieth-Century Flute Music my flute listening included some Jethro Tull, some Herbie Mann, highly inventive jazz players such as Eric Dolphy and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and the occasional pop-rock recording, prominently the Beatles' "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away" (1965) and Canned Heat's "Going Up the Country" (1968).

As that limited palette suggests, this article began not with a great passion but with a day of record shopping. As I knelt outside a used-record store that was giving away boxes full of classical-music LPs, Twentieth-Century Flute Music spoke to me for various reasons: The above-mentioned artists had primed me to appreciate flute music. I'm a bit familiar with one of the composers included on this album, Edgard Varèse, whose music was championed by a musician I'm quite familiar with, Frank Zappa. The record's label, Nonesuch, pretty much guarantees quality in whatever genre. Finally, this two-LP set was both a promotional copy, which in record-collector terms is gold because it means the albums were among the first ones pressed from the master, and in pristine condition, as though played sparingly if at all. Sold! to the dude who'll either cherish this artifact or find a good home for it.

As a collection of sounds embedded in grooves on vinyl, Twentieth-Century Flute Music lived up to my expectations. The recording is stellar, the playing exquisite, the translation of analog technology to my analog/digital sound system a delight. The album provides the warmth and richness that listeners associate with LPs. It's easy to imagine the players in the room--their room, my room--but it's also a pleasure to have that sense of the moment, of an event being created for your ears, that comes from a stylus in a groove. (CDs can sound wonderful, but they're ultimately too abstract, being hidden in drawers where ones and zeroes meet their destiny. Digital files, well, they represent music the way some canned goods tossed into a pot and heated can be food, not quite cooking.)

But what about the Twentieth-Century Flute Music itself, apart from its analog representation? This collection provides a strange experience. On the one hand, flutist Sollberger has assembled an admirably unified program that takes the listener into an undisturbed head space, where individual notes and juxtapositions can be savored. In his liner notes, Sollberger explains that "By the 20th century, the flute had come to be regarded as fixed, finite, known . . . [yet] a whole new configuration of attitudes with regard to the flute has arisen in response to the need of today's music for enormously expanded skills of differentiation and contrast in such areas as articulation, dynamics, timbral modification, and vibrato. . . . Consider, for example, that conventional flute-playing requires knowledge of at most 40 or 50 fingerings, yet the number of possible fingering combinations is in the thousands--and we are only beginning to explore these possibilities."

On the other hand--even while marveling at Sollberger's skills throughout--it's very difficult, at least to the untrained ear, to differentiate the pieces here or identify the composers. That's not a criticism, just an observation. The similar-soundingness may have resulted from the choice of compositions, from the players' styles, or from the nature of solo flute music.

One piece, Preston Trombly's Kinetics III (1971) employs a tape of electronic sounds created at Yale University. That's the piece easiest to identify.

Otherwise, we inhabit a place where the sound of a flute drifts across the landscape. Quick percussive noises--plonks, plunks (these are not technical terms)--appear, disappear. The closest, most readily available comparison might be the composer Jerry Goldsmith's avant-garde score for the 1968 movie Planet of the Apes. Twentieth-Century Flute Music transports us to a sound world like that one.

In addition to his myriad scores for blockbuster Hollywood movies, Goldsmith composed orchestral music for performance, was academically trained, and sometimes employed the abstruse twelve-tone system (if you don't know what that is, please do a web search; I'll just say that it doesn't yield hummable melodies or crowd-pleasing dynamics).

The reference to Goldsmith's Apes' music, meant to clue in as many potential listeners as possible, might amuse or horrify the highly credentialed Harvey Sollberger. In addition to playing the flute, Sollberger is a composer, a conductor, and the founder (with pianist Charles Wuorinen, in 1962) of the groundbreaking ensemble The Group for Contemporary Music. Throughout his career, Sollberger has championed new and challenging music by composers such as John Cage, Lukas Foss, and Lou Harrison--but those names are all on one album and among the most recognizable in his discography. Like his other recordings, Twentieth-Century Flute Music introduces us to lesser-known figures.

Side 1 opens with Varèse's Density 21.5 (1936), a classic with which, according to Sollberger's notes, "the imaginative reconception of the instrument may be said to have begun." In particular, Sollberger credits Varèse's "recognition that the flute has many 'voices.'" If you know Varèse from his percussion pieces, be prepared for a surprise, because Density 21.5 is all flute. Notes glide, swoop, dip, hang, and flutter in what feels like crystalline air. Were the instrument a saxophone, clarinet, or trumpet, we would not marvel at the variety of approaches here.

After a brief pause, Side 1 moves seamlessly into Charles Wuorinen's Flute Variations I (1963), which is followed by his Flute Variations II (1968). These pieces are unrelated except that they were composed for Sollberger and involve twelve-tone operations. Wuorinen follows Varèse in giving the flutist only empty space in which to explore the instrument's possibilities. Here the notes sometimes move far more rapidly than in Density 21.5, becoming at times percussive. Flute Variations II involves the high and low register, with some particularly Japanese-sounding drones, some of them ghostly. Sollberger's breath control during these extended lines seems exceptional. The final line does a delicate dance, then cuts off.

At the start of Side 2, Wuorinen joins as pianist on Peter Westergaard's deliciously titled Divertimento on Discobbolic Fragments (1967). Westergaard wrote this piece at Sollberger and Wuorinen's request, and it enables them to play in sometimes delicate, sometimes parrying counterpoint. The flute repeats drawn-out notes as a refrain, like the holding of breath except beautiful, while the piano provides isolated percussive notes like punctuation marks. At six movements and ten minutes, this is the longest work in this collection.

Divertimento's neighbor on this side, Burt Levy's Orbs with Flute (1966), at just under three minutes, is the shortest piece here. However, Sollberger calls Orbs with Flute "one of the first pieces to employ significantly the wide range of new timbral and articulative resources known today as extended techniques." The flute ranges, with the definite sense of floating objects and the feel of a John Coltrane saxophone solo, with note clusters and flutters and a willingness to be unperturbed.

Mario Davidovsky's Junctures (1966) adds to Sollberger's flute the clarinet of Allen Blustine and the violin of Jeanne Benjamin for what Sollberger calls "a 'music of intervals.'" As with Divertimento, the instruments play in multidimensional counterpoint. Clarinet, violin, and flute sound like siblings comfortable with one another, their unique viewpoints--extended statements, quick articulations--coalescing into a conversation worth following.

Side 3 brings Luciano Berio's classic Sequenza (1958). Here the solo flute gives the uncanny impression of thinking, if thoughts were sometimes high-pitched notes darting and swooping, then reaching a conclusion. Trombly's Kinetics III, composed for Sollberger, presents a kind of live-plus-electronic chamber music. The opening features a burst of mechanical sounds. The flute then progresses confidently on its journey, staying mainly in its middle range, and the noises--beeps, tones, hums, oscillations--jump in unexpectedly, establishing themselves as a major component by the end.

Wuorinen returns on piano for Kazuo Fukushima's Three Pieces from Chu-u (1964). Here again, as on Westergaard's Divertimento, the interplay consists mainly of long, melodic notes from the flute--here with an aching beauty--and short, interruptive notes from the piano.

Side 4 opens with Nicolas Roussakis's Six Short Pieces for Two Flutes (1969), where the second flute is played by Sophie Sollberger, wife of Harvey. The intertwining of two flute tones suggests organic imagery, such as fish navigating a small body of water, even challenging each other, or cloud formations changing in wind. Roussakis leaves lots of room for movement, with notes ranging from low and steady to high and whistling. Hints of melody never cohere--which is, again, not a criticism, just an observation. This piece segues perfectly into Roger Reynolds's Ambages (1965), to the point that Harvey Sollberger could at points be playing two flutes, except that at the end, a single flute casts one forlorn, slightly inconstant note.

These four sides of music run about an hour and a half, adding up to a kind of flute-forward tone poem. Whether they merely hint at the flute's expressive possibilities, whether such explorations have carried through the past five decades, I leave for you, adventurous readers and flute enthusiasts, to determine. I simply recommend that you listen to the flute, particularly but not solely on Twentieth-Century Flute Music.