VAN MORRISON

Wavelength tuned in

by Pat Thomas

(February 2021)

Van must have enjoyed his experience at The Manor recording A Period of Transition, because he returned to record his next album, Wavelength. Van brought in two musicians from his early days in Belfast. Keyboardist Peter Bardens had been one of the transient members of Them circa 1965 when they seemed to change members every 15 minutes. Guitarist Herbie Armstrong had been in various rival Belfast bands back in the day - not to be confused with guitar player Jim Armstrong, who actually was a member of Them for longer than most. Bobby Tench also played guitar on Wavelength - Jeff Beck fans will recognize his name from 1971's Rough and Ready and '72's self-titled Jeff Beck Group, on which he served as vocalist and rarely played guitar - leaving that up to the former Yardbirds maestro. After laying down most of the tracks in England, Van took the tapes The Band's Shangri-La studio in Malibu, California, for additional instrumentation from the eccentric Garth Hudson.

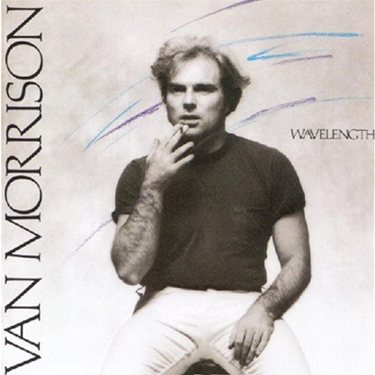

Despite being mainly recorded in England, Wavelength was thematically Van's most American album. There were a couple of song titles, "Venice U.S.A." (a seaside part of Los Angeles) and "Santa Fe" (the state capital of New Mexico). There's the Southern California sheen of the album cover photo by photographer Norman Seeff - responsible for many Hollywood stars' portraits and for that striking image of Joni Mitchell on the cover of her Hejira LP. Another shot from the Seeff session was circulated in countless magazines of Van wearing the same outfit while holding that most iconic American artifact of the 1960s-70s - a portable transistor radio - inspired by the title song, which celebrated the musical airwaves as well as connections between people, as in "Are we on the same wavelength?"

This album would mark the beginning of a spiritual quest for decades to come, reflected in his songs and behind the scenes in his personal life - but on the American West Coast in the 1970s, thousands of baby boomers had already been seeking that out via Werner Erhard's est (touted by ex-Yippie Jerry Rubin amongst others), Tim Leary's former LSD buddy Richard Alpert's teachings (by then calling himself Ram Dass) and a potpourri of mellow thoughts emanating from the Esalen Institute in Big Sur.

I'm not saying that Van explored any of these specific things, but as a longtime resident of the San Francisco Bay Area he would certainly have been aware of them, and he'd follow his own paths over time that would blend hundreds of hours of self-study (reading), exploring various Western and Eastern philosophies, hanging out in churches and even dabbling in Scientology under the direct auspices of L. Ron Hubbard, who got thanked on 1983's Inarticulate Speech of the Heart album.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves now because Wavelength isn't a full-on exploration of any of that. Some of that begins on this album and goes deeper later. Oh, and before you go running screaming from the room from the mention of Scientology - Van was there briefly - he's far too cynical to go deep or stay long. Stranger and longer than Morrison's visits was Beat Generation writer (Naked Lunch, Soft Machine, Nova Express) William S. Burrough's commitment. Apparently Old Bull Lee (as Kerouac calls him in On the Road) spent most of the 1960's going 'Clear' and nearly obtaining an 'Operating Thetan' role. It doesn't get much higher than that! Yet, Burroughs was notoriously more of a cynic and curmudgeon that Van ever was... I don't think Morrison ever connected with Burroughs's sci-fi drug-fueled writings (I did a bit, but Bill was too reptilian for me to fall in love with him), but Van and myself do have Kerouac's On the Road and Dharma Bums and fellow traveler Allen Ginsberg in common.

The morning after I write the paragraphs above, it's Van's 75th birthday (August 31st, 2020) and I post about it on social media. Minutes later, I receive a call via Facebook messenger from Paul Wexler - son of Jerry Wexler, legendary co-owner of Atlantic Records, the brains behind Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin's best recordings of the 1960s, producer of Bob Dylan's Slow Train Coming, and co-author of the song "(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman" with Carole King & Gerry Goffin.

Paul and I have never communicated before, but my post intrigued him and he felt like reaching out to discuss Van, whom he knew during the 1970s when Paul worked at Warner Brothers Records - the label Van was signed to then. Here's the weird part - he was involved in the recording of Wavelength and wants to share a story about it! Talk about kismet synergy...

After the release of A Period of Transition, Van was still feeling a bit lost artistically, and Paul Wexler and Van discussed reviewing the dozens of hours of Morrison out-takes and unused songs (left over from albums Van had already recorded) that were in the Warner Brothers vaults for a possible release. They started off listening to the tapes at Brother Studios in LA. In this case, the Brothers were not Warner, but Wilson. Dennis, Carl, and Brian of the Beach Boys owned their own studio. This discussion with Wexler reminded me that Van's name popped up in Ken Sharp's 2018 oral history The Making of Pacific Ocean Blue - chronicling the making of Dennis Wilson's 1977 moody masterpiece, Pacific Ocean Blue, an album the rivals John Lennon's solo debut, Plastic Ono Band, Big Star's 3rd and Neil Young's On The Beach for capturing a nervous breakdown on vinyl. Harsh sandpaper vocals combined with bizarre instrumentation, dark haunting melodies, and Phil Spector-ish washes of sound filtered through a drug-fueled haze.

Before the infamous Tate-LaBianca murders, which Charles Manson oversaw in August 1969, Dennis and Charlie enjoyed a twisted friendship of sorts - I say this partially tongue in cheek, but Pacific Ocean Blue could be the soundtrack to the Manson-esque apocalyptic end of the Beach Boys' sunny Southern California dream.

In September 1968, Dennis recorded a Manson song with the Beach Boys. Originally titled "Cease to Exist," it got slightly reworked musically and lyrically. "Cease to Exist" became "Cease to Resist" and then was called "Never Learn Not to Love," and when the song appeared on the Beach Boys February 1969 album 20/20. For Manson himself, here's the rub - Charlie's name was removed completely and Dennis was credited as the sole songwriter. Theorists speculate that this incident inspired Manson to have his Family commit some of his murders. Sharon Tate was living at a house formerly occupied by Dennis's friend record producer Terry Melcher - who along with their buddy Gregg Jakobson had expressed interest in recording Manson for an album of his own. When that didn't happen, coupled with the Beach Boys debacle, ol' Charlie was pissed and needed to send a message. Jakobson testified at a Manson Family trial about these events.

Shortly after Charlie Manson's arrest, the Musicians' Local Union in LA wrote the Los Angeles Times and said that they had checked their union records and that Manson definitely was not a musician. Just so there'd be no confusion, they stated that most musicians were good clean fellows who believe in hard work and the American way of life.

Jakobson remained close with Dennis through the years and wound up co-producing and cowriting (Jakobson as lyricist) several of the songs for Pacific Ocean Blue. Now I know (because of Paul Wexler's phone call) how Van came to be mentioned in Ken Sharp's oral history. Jakobson says:

Dennis was very experimental. Sometimes he'd show up at night [at Brother Studios] after going out to dinner and having a couple of glasses of wine, and he'd bring some girls back from the restaurant and try to get them to sing on a chorus part. Usually it didn't work out, but once in a while it did. There were people like Van Morrison who came into the studio and Dennis would try to get something out of them.Sadly, if anything was attempted with Wilson and Morrison, nothing has ever leaked out. not even on the expansive 2008 double CD's worth of previously unreleased Pacific Ocean Blue-era recordings.

However, Van liked what he heard of his own vintage recordings at Brother Studios, so Wexler booked six weeks of studio time at The Manor in England so that Van could take his time and carefully add or re-record additional vocals. Very early in the process, Van got frustrated because one of the songs was out of tune; it had been recorded in the wrong key for his voice. With today's technology, the recording could be adjusted, but in 1978, it was impossible to fix. Van wanted to abandon the entire project. Paul, having picked up a lesson or two from his father along the way, sought to salvage the situation and make his bosses at Warner Brothers happy.

He reminded Van that they had prebooked six weeks and if they left so soon, they'd still be charged for at least three weeks, so why not record some demos or cut new material? Van agreed and Paul began calling contacts in London to round up musicians such as Peter Bardens and Peter Van Hooke. At this point in the story, I interrupted Wexler to point out that decades later, a compilation of unreleased Van material from the Warner's years was released - The Philosopher's Stone in 1998- but Paul wasn't aware of it.

He reminded me that this was the era of punk rock getting a lot press in the UK, and aging rockers like Van were skeptical of this energetic but primitive music. Wexler recalls wearing a Ramones T-shirt and running into Ringo Starr who sarcastically countered, "So this is who is taking over from us, eh?" Van wasn't impressed by the likes of the Sex Pistols either. Nevertheless, in the punk esthetic from the media and the record buying public was looming over Morrison as he began recording Wavelength.

Keep in mind that Paul Wexler's DNA was steeped in his father's productions - such as the searing vocalizing by Aretha Franklin on Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You. Paul told me,

I've never witnessed anything like when I saw when Van cut the vocal for the song "Wavelength" - it effortlessly flew out of him; it was overwhelming. Just an incredible take! Van came back into the control room to listen to the playback and he quickly agreed. He jumped up on the Trident mixing board, ran across it and sent a box of 2-inch reel-to-reel tape sailing when he kicked it while shouting, "Fuck this punk rock shit!"Wexler adds, "Wavelength was the most rock n' roll record Van had recorded since Them, inspired by or because of the punk movement." While nobody would mistake Wavelength for punk or new wave, it was Morrison's most FM-radio friendly recording, just missing the American Top 40 charts by two points. Although The Manor's inhouse producer and engineer Mick Glossop had encountered Van while working on A Period of Transition, Wavelength solidified their working relationship for years to come - his name crops up on the slick polished recordings that Van delivered for Avalon Sunset, Enlightenment, Hymns to the Silence and several more albums. Not only did the recording involve foward look (at least in terms of the engineering staff), it also involved a look back. Van returned to Brooks Arthur - who had recorded his Bang Records material, like "Brown Eyed Girl" and Astral Weeks- to do the final mixing of Wavelength. And if the music of "Wavelength" partially harkened back to the Them era, it also glanced ahead with its use of synthesizers which would become prevalent on future albums. After Wexler and I hung up, I saw something I'd never noticed before on the back of the Wavelength CD: "Production Assistant: Paul Wexler."

"Kingdom Hall" - what a rockin' gospel album opener celebrating the meeting place for Jehovah's Witnesses. Not since The Who placed "Baba O'Riley" as the explosive first song on Who's Next in 1971 had a popular artist started an LP off with an FM radio friendly song that name checked religion. "Baba" was Meher Baba, an Indian mystic that Pete Townshend was obsessed with (inspiring much of Townshend's best work between 1967 and 1980) who declared himself an Avatar in 1954. "O'Riley" was Terry Riley - not a religious icon, but a musical one who spearheaded electronic and avant-garde music during the 1960s. 1964's In C and '69's A Rainbow in Curved Air are both essential purchases for any record collection. Less interesting, except for Velvet Underground completists, is Church of Anthrax, Riley's 1971's recording with John Cale.

Van Morrison's upbringing wasn't particularly religious. He father George was raised a Presbyterian but followed no organized religion and was likely agnostic. During the 1950s, his mother Violet was a steady member of the Witnesses for a few years and Van occasionally accompanied her. But by Van's adolescent, the Morrison household was religion free, because his mother didn't sustain her beliefs. Unlike most people in Ireland, the Morrison's were neither Protestant nor Catholic but they leaned toward Protestantism culturally. My fellow Morrison devotee Howard DeWitt writes in his 1983 Van book The Mystics Music, that "Kingdom Hall" is "an autobiographical piece about Van's visits to the Marin County Jehovah's Witness Kingdom Hall." Given Van's exploration of religions that seems plausible (and a quick phone call to DeWitt who lived in the Bay Area in that era confirms it as truth). In fact, in recent years when Van visits Los Angeles, he can be found singing at Sunday services at Agape Church - check YouTube for several performance videos.

DeWitt adds that "It is an unusual song since Jehovah's Witnesses don't use choirs in their services." To me, that thought ignores both the universal spirituality that is at the core of Morrison's message and Van's devotion to R&B. I feel uplifted just listening to this track without being attracted to a specific sect. However, I do embrace Howard's thought that "perhaps this song is an allegorical comparison between a local Kingdom Hall and one of Van's favorite small concert halls, the Inn of the Beginning in Cotati, California." I'd add The Lion's Share in San Anselmo. Several delicious Van Morrison bootleg CD's circulate from there: Stormy Weather in San Anselmo compiles highlights from the early and late shows of February 15th, 1973. Notably, it includes a rare performance of Van singing Fred Neil's "Everybody's Talkin'" (best known via Harry Nilsson's version as the theme song for the 1969 movie Midnight Cowboy). The 2 CD set My New World Crystal Ball has the complete early and late sets of August 8, 1971 including solo acoustic performances by Van before the band and street choir (including Janet Planet, his wife at the time, and Martha Velez) join him. For something a bit odd, search out Velez's 1969 album, Fiends & Angels. She belts it out like Bonnie Bramlett (of Delaney & Bonnie) or Linda Ronstadt backed by the cream of British rockers of the era: Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce, Brian Auger, Christine McVie, Jim Capaldi, Mitch Mitchell and others. Eleven songs from a May 16 1971 Inn of the Beginning gig are included on a double CD Into The Mystic which has the best quality (and the most complete) of the oft-circulated September 11, 1971, Pacific High Studios KSAN radio broadcast, which is the most bootlegged Van concert ever.

All six minutes of "Kingdom Hall" was issued as a single but failed to chart - which is surprising because it's such an immediately grabbing song. Perhaps a three or four minute edit would have done the trick. This is a pop song like "Brown Eyed Girl," albeit more sophisticated. The ear candy of the do do do's of "Kingdom Hall" aren't unlike the la la la's of "Brown Eyed Girl."

Unlike the muddy blend of Van, backup singers and horns on A Period of Transition, the ensemble on Wavelength is tight. Everyone sounds more rehearsed, the horns have been replaced with synthesizers which cut through more clearly; the additional vocalists are more engaged with Van's vocal. Peter Mills writes in his 2010 book, Hymns to the Silence, that "Kingdom Hall" "delivers a strong sense of inclusivity and belonging, community and congregation." I agree. As stated before, I didn't feel the need to run over to the Kingdom Hall specifically when I first heard the song circa 1987, but it did reinforce my gut instinct that spirituality is what's happening. I'd picked up on the same universal spirituality when I read Beat authors Kerouac and Ginsberg a few years earlier. There's Catholicism in Jack's work, but it's blended with Buddhism and Eastern thought. Allen was Jewish at his core but couldn't be contained by any that or any other testament. Every time I drive by a Kingdom Hall, I do think, "Hmmm...Van...I wonder what he knows that I don't."

After the heavy themes delivered on "Kingdom Hall," "Checkin' It Out" provides some lite 'n breezy relief, or does it? On the surface, it's a catchy ditty built around the phrase "takin' it further, checkin' it out" as if Van is discussing casual dating. But he slips in lines like "there are guides and spirits to guide us" and "you meditate"- perhaps Van was more plugged into that West Coast New Age / Self-Help movement than I thought. Which reminds me: I often use the word "meditate" as in "let me think about that for a while." I was once on the phone with the infamous Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols, although he'd become John Lydon of Public Image Ltd. by that time. I did some music business deals with him (reissuing the first two PIL albums) and he was reluctant to write any reflective essays to accompany the new versions. I suggested he "meditate on it" and get back to me. He launched into a tirade of "What are you, some dumb ass hippy? What's this meditate shit?" OK, John, calm down. On a later call, he was being yelled at in the background by his wife Nora who demanded he get off the phone and run an errand for her. I thought, "Damn, even the King of Punk has to answer to a higher power."

I don't remember "Natalia" at all until after a few plays, when it kinda comes back to me - it's got a smooth FM-rock familiarity. An upbeat pop song with glossy backing singers- it's so radio friendly that it was released as a single in America (including a promo-only radio edit that cut it from 4:04 down to 3:40), Canada, the UK, New Zealand and Australia - but I believe it failed to chart anywhere. However, Peter Mills recalls in his Morrison book that it was the first Van song that he ever knowingly heard on British radio. Like "Brown Eyed Girl" - it consummately blends bliss and nostalgia. The euphoric sentiment reminds me of Dylan's "You Angel You" from 1974's Planet Waves: "If this is love - then gimme more and more and more." I always thought the title Planet Waves was a nod to Ginsberg's 1968 book of poems Planet News.

Damn, "Venice U.S.A." has the same type of repeating riff as "Cleaning Windows" from 1982's Beautiful Vision - and despite hearing "Cleaning Windows" many times before, I suddently realize they both have a reggae thing going on. It's more prevalent in "Venice," which I don't know nearly as well. Vocally. both songs are spoken-blues, with Van testifying about events from his past. When he evocatively cries out, "And I'm cryin'... filled with joy" - the "cryin'" sounds no less painful than the "I cried for you" of T.B. Sheets. That's the blue-eyed soul magic of Van the Man.

I'm now beginning to realize why I haven't spent much time with this album over the past 30 years - "Lifetimes" is as dull as dishwater. Plodding, no melody, no hooks, no memorable lyrics.

That ends side one of the original album.

Gurgling bubbling synthesizers were a peculiar beginning to a Van Morrison song in 1978. Bordering on prog-rock territory for about a minute with traditional piano and organ sounds underneath while a high-pitched Van croons soulfully on top like a wannabe Barry White, "you turn me on... oh mama, oh mama." For a moment, you're wondering if this is something from Marvin Gaye's Midnight Love, which has "Sexual Healing" owhich. As the tempo picks up and the repeating synth pattern increases in speed - it's more like electronic maverick Larry Fast's work on Peter Gabriel's 2nd solo album from 1978. Cue Gabriel's "On the Air."

All that eccentricity gets overrun by Peter Van Hooke's robust drumming locked with Mickey Feat's throbbing bass but the electricity continues in the form of Peter Barden's nonstop synth soloing - now moving into a new wave vibe like keyboardist Greg Hawkes of The Cars (their debut LP was everywhere in 1978). The electric power is also generated by Bobby Tench's lead guitar playing - very much like Bobby's former boss Jeff Beck or Beck's protege Mick Ronson playing with Van on that 1977 Dutch radio broadcast. As Paul Wexler pointed out to me, this is Van's most rocking work since Them with a spectacular vocal to boot. Yet, I'm struggling to find the right verbiage to do justice to the cornerstone of this album.

"Wavelength" is blending the euphoria of listening to the radio like the Modern Lovers described on "Roadrunner" with new age telepathy explored elsewhere on this album ("Checkin' It Out). It was partially inspired by Van's adolescence spent listening to the Voice of America broadcasts in Ireland. First started during World War II, VOA continues to bring American content to foreign audiences around the globe. See also R.E.M.'s debut single "Radio Free Europe." Thanks to Van scholar Peter Mills for pointing out the obvious (which I'd missed): the synthesizers are replicating the sonics of scrolling through the band waves of a radio. Tuning in and turning on, as in Joni Mitchell's 1972 single "You Turn Me On, I'm a Radio" or Van's own "Caravan" - "turn it up, little bit higher." Morrison would address the pleasure of radio again on "In the Days Before Rock' n' Roll" on 1990's Enlightenment. But would he combine it with neuroscience again? Hmmm, not that I recall but I've got a few dozen albums left to explore.

The second song on side two of the LP was a sprawling seven-minute epic that consisted of two songs blended together: "Santa Fe" (cowritten with Jackie DeShannon) and "Beautiful Obsession" (like most of his recordings, penned just by him). Morrison had spent time in 1973 helping DeShannon birth an album for Atlantic Records that never gelled - however, her version of "Santa Fe" emerged in 2003 as a CD bonus track for her Jackie album. However, the best place to get all four of her Van Morrison-produced rarities is on a 2015 DeShannon CD, All The Love: The Lost Atlantic Recordings.

Jackie's version of "Santa Fe" is lively and colorful - everything her version of Van's "Flamingos Fly" isn't. But despite her sturdy vocal and an animated arrangement with multiple horns and a prominent electric bass not unlike Jaco Pastorius on Joni Mitchell's Hejira, I just don't feel this song. Compared with Jackie's, Van's version is slower, less flashy (and not nearly as busy, as it doesn't have those horns).

His vocal conjures a bit of his uncommon juju, but it's not enough to sustain my interest. As the song moves into "Beautiful Obsession," it occurs to me, that this isn't a separate song at all, but just Van doing what he does best - vamping and improvising vocally at the end of a lengthy song. My cynical side says he gave it a different name to grab more songwriting royalties from his record company. Neil Young pulled a similar trick on Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's Deja Vu, when he divided the song "Country Girl" into three separate titles: "Whiskey Boot Hill," "Down Down Down," and "Country Girl (I Think You're Pretty)." Cynicism aside, Morrison's oratory during "Beautiful Obsession" is the highlight of the whole mess and rescues it as being just slightly better than "Lifetimes" - yet, this long track is another reason that Wavelength hasn't been in steady rotation in my household.

"Hungry for Your Love" was used in the 1982 movie An Officer and a Gentleman and even appears on the soundtrack LP right after the popular song that was specifically recorded for the movie, Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes's duet "Up Where We Belong." "Belong" was co-written by Jack Nitzsche (Neil Young's orchestral arranger of choice such as on the Buffalo Springfield's "Expecting to Fly"), fabled Indigenous Canadian folk singer Buffy Sainte-Marie and Will Jennings who wrote the lyrics to many songs on Steve Winwood's Arc of a Diver album. "Hungry for Your Love" sits perfectly amongst that early '80's soundtrack music - so polished you can see your reflection in it. While Van certainly went on to make even more glistening recordings like the entire Avalon Sunset album - there's a certain earthiness, a touch of dirt under his fingernails on "Hungry" that makes it a hundred times edgier than what "Up Where We Belong" is: pure dreck and dross.

On the surface "Take It Where You Find It" seems analogous to "Hungry" but only sonically. This eight-and-a-half minute narrative encapsulates Van's search for America - beaer in mind that this album has two songs here named for American cities, "Venice" and "Santa Fe." He mentions finding a purpose on the "road" and "lost dreams and found dreams" - topics embraced by Jack Kerouac in On The Road. which Van namechecks on 1982's "Cleaning Windows. "

I've touched on Van's (spiritual) quest thus far - and "Take It Where You Find It" is part and parcel of his searching, but what makes this song singular is that Morrison is focused on the American Dream or his vision/version of it. On the album His Band and the Street Choir, during the final cut, titled "Street Choir," Van ask,

Why did you leave AmericaWhomever he's referring to, he's disappointed that they've bailed on his United States of adventure, but nearly a decade later, he's not giving up on it. He won't back down, he's "gonna walk down the street until [he sees] his shining light," and he encourages everyone else to "take it where you can find it." I'll admit, I have absolutely no memory of ever hearing this song before (but I have several times years ago) and it's the sleeper track of the record. Reportedly, it's something he worked on quite a while. In Can You Feel The Silence?, Clinton Heylin mentions Van starting it in the spring of '77, a full year before recording Wavelength. He quotes Van as remarking "[I] carried it around with me for a long time... not really knowing or caring what it was about, I tried changing it... But that line [about 'lost dreams and found dreams in America'] kept sticking." Van adds, "I couldn't get away from it." Ever the charming contrarian, Van told the New Musical Express in their October 3, 1977 issue: "[Take It Where You Find It] has nothing to do with any American Dream; it's not about the country, it's about my personal experience. A lot of people think I went to America and now I'm involved in some American Dream... it's cliched... garbage." Van, I think you're holding back, tell us how you really feel.

Why did you let me down

And now that things seem better off

Why do you come around?