Suicaine is Painless

A Paul Westerberg primer by Alan K Crandall

(March 1999)

About a month ago, I had the pleasure of meeting Peter Guralnick, whose books on

music ("Feel Like Goin' Home," "Lost Highway," "Sweet Soul Music" and others)

are easily at the top of my list and a major personal inspiration. Guralnick was

promoting his new book, "Careless Love," the second half of his ambitious

two-volume biography of Elvis Presley (an aside, these two books constitute the

definitive Presley biography, so now there's no excuse for reading Albert Goldman).

Talking about some of the challenges that he, as a fan, had to meet in order to write

objectively about Presley's life and career, he mentioned that the biggest one was

probably accepting the fact that, regardless of what he (Guralnick) might have

wanted Presley to do with his music and career, Elvis had plans of his own, and, in

fact, despite the myth of Col. Parker's evil influence, Presley ultimately did pretty

much what he wanted to do. In other words, Presley wasn't lead down the path to

schlockdom by any forces other than his own; his fans might have wanted him to

stay forever the king of rock'n'roll, to be the greatest white r&b singer ever, but

Presley wanted first and foremost to be a professional entertainer who sang all

kinds of music, and in the end that's exactly what he did. Regardless of whether you

or I or Guralnick missed "Mystery Train," we got "Bridge Over Troubled Water"

instead because that's the choice Presley made for whatever reason (professional,

artistic, or drug-induced) and if we care about Elvis Presley or his music, we just

have to deal with it.

It immediately struck me that much the same could be said of Paul Westerberg,

whose then-forthcoming new album was being hotly debated in the newsgroups (by

those who'd managed to get their hands on advance releases) as being the biggest

disappointment yet from a guy who, since splitting from his legendary former band,

has steadfastly refused to give the fans what they wanted, instead sticking to his

own guns and recording a trio of albums that have cost him a huge chunk of his fan

base, crashed and burned commercially, and left him farther out on the fringes of

popular music than anyone might have imagined possible ten years ago.

I'm determined to get through this without saying any more than I have to about The

Replacements. They happen to be one of my all-time faves, but I've written about

them before, and I think I've said pretty much all I had to say. Besides, I'm not sure

there's any band that's had more written about them in the past ten or fifteen years

… I can't prove it, but I'd be willing to wager The Replacements got more press

(and from the mainstream rock rags, too) between 1984 and 1990 than Bruce

Springsteen or The Clash or any number of other critics darlings ever did during

their respective heydays. And if you're reading this, you've probably already read

plenty of it, and it's a story that doesn't need to be told again. Having said that, I

know I'm going to have to bring them up, if only for the sake of delineation. So let's

get on with it.

I think a big part of their appeal was that they seemed so anomalous… I mean, you

could accept that this bunch of stumblebums could come up with first-rate

punk-rock jokes like "Gary's Got A Boner," but who'd have thought they'd have

something like "Sixteen Blue" in them? That their drunken, hapless frontman could

turn a lyric that startled you with its rightness and depth of feeling was something

you just hadn't counted on… I know that for a few years, I used to greet each

Replacements record wondering if that last one hadn't been a fluke. But they

continued to deliver the goods.

Something changed, though; as the decade wore on; something that began to split

their fan base into armed camps and threw old followers off even as it attracted new

ones. It wasn't signing to a major label, or turning their back on "punk rock," or that

they started playing more "professional" gigs (less drunken fooling around, more

actually playing their own good songs), or firing Bob Stinson, or appearing on

MTV, or getting a little airplay, or even the move toward more polished studio

performances -- though ALL of these things brought them under fire.

In the beginning, when Paul Westerberg came out with an unexpectedly great song,

it seemed like an accident (even when it kept happening). His most inspired lyrical

moments seemed to fall at random; they weren't perfect -- a great turn of phrase

might follow a merely average one or, if all else failed, an unintelligible shout, a

mumble, a laugh or the sound of something breaking. You never got the sense that

the songs had been labored over, each line weighed for its worth (regardless of

whether this was true or not). It sounded instead like Westerberg just opened his

mouth and whatever came tumbling out, be it genius or dumbness, was what went

on tape.

But by 1989's much maligned Don't Tell A Soul, things were different. Not that the

songs weren't good. What changed is that Westerberg, who once seemed to write

outstanding songs by accident, now wrote them deliberately. The sense of

spontaneity was gone, replaced by a sense of craft. Now the songs did sound

perfect, like every line had been weighed for its worth. In a sense, they were better

than ever, but something had been lost, too. Compare a song like "My Little

Problem" off of the later All Shook Down to any of even the most standard-issue

Replacements rockers that came before it, and the difference is obvious -- "My

Little Problem" is a fine slab of Stonesy rock, it's got clever lyrics, a good hook, a

smokin' guitar solo. But it's also by the numbers… that isn't to say it's bad, but

nothing about it surprises you, which couldn't be said of very much The

Replacements did before 1990.

For all the heat that Westerberg's taken, it was inevitable. I can't claim to know

exactly what went through his mind over the years, but I can make a guess, and I

trust its accuracy enough to put it down in print. Here's a guy with a natural gift for

songwriting, a masterful ability to articulate adolescent insecurities and anxieties. Yet

I suspect that in 1980, when first Replacements album was recorded, he never

expected to accomplish much more than to play his punk-rock parodies in bars, his

more heartfelt songs never to be heard outside of his own basement and his

manager's boom box. Flash forward a few years and suddenly his band is the Next

Big Thing, and he's being showered with accolades as the greatest songwriter of his

generation. Certainly by 1984, it must have been clear that his joke band had the

potential to reach a much broader audience than the kids down at the local punk

club; that someone out there (a lot of someones, perhaps), actually wanted to hear

those personal songs. Westerberg must have realized that suddenly the dream he

never dared to put any hope behind was on the verge of coming true, and it's

anything but a surprise that as he came closer to it, he knew better than to blow his

chance. So he got down to business, and the jokes stopped, and anyone who

refused to be his ally got shown the door. Westerberg's been condemned more than

once for axing Bob Stinson, and alienating drummer Chris Mars, but I suspect

almost anyone else in his position would have done pretty much the same thing.

Sometimes, when you follow a dream, you have to push a few people overboard.

That's a terrible thing to say, but it's true, and that's why, if you look into any

successful artist's life story, there's always a few souls out there anxious to tell you

what a no-talent scumbag asshole that artist is or was.

So Westerberg bid goodbye to The Replacements as a band with All Shook Down

and goodbye to The Replacements as a concept with 14 Songs a few years later.

And right away the debate began, and it's never let up. Few seemed to think that 14

Songs contained the same inspiration that fired The Replacements best moments.

Some charged that he'd sold out, that he'd stopped rocking, that he should go back

to drinking. Others were just glad to have any new music from him at all.

The short and long of it was that Westerberg had traded inspiration for craft. As the

title (and contemporaneous interviews) made clear, this was Westerberg the

Songwriter, not Westerberg the drunken rocker, former Replacement, or godfather

of punk. The songs were all "good" in the sense that great care had been taken to

make them good. Each was a carefully thought-out entity, not an accident that

happened to contain greatness. But being good in that sense, unfortunately, didn't

make them memorable. There were certainly moments -- I like the Keith

Richards-y guitar on "Knockin' on Mine," the Faces-ish stomp of "Silver Naked

Ladies" (which most fans seem to hate unanimously, but I take it as a sign that

Westerberg hadn't forgotten that good rock`n'roll doesn't have to be serious, or

deep, or meaningful or even lyrical), and especially the weird "Black-Eyed Susan,"

which the kind of out-of-left-field surprise bit of brilliance that had caught my ear in

the first place. But too much of the album was just slight. "World Class Fad" was a

good rocker, but it was well-trodden ground both lyrically and musically for

Westerberg. "Down Love" wouldn't have sounded out of place on the early "punk"

Replacements albums, but it sounded forced here. The more serious songs tried so

hard to be lyrical that they lost sight of such details as a good hook, a pitfall he'd

avoided in the past. Worse yet; Westerberg had declared (in a bizarre Rolling

Stone interview that read more like a psychotherapy session than an artist's Q&A)

that "wimpy" to him meant, not quiet music, but "cute" music. A very reasonable

statement that only made it more troubling that songs like "Dice Behind Your

Shades" and "Mannequin Shop" were "cute" in the worst possible way. It was an

inauspicious showing for an artist of Paul Westerberg's reputation. The follow-up,

1996's Eventually seemed even more confusing. Here the songs were so tightly

crafted, and polished to a perfect pop sheen, that the whole album seemed empty.

The rockers mostly sounded forced and stiff, the other songs simply too slight

(despite their merits, and there were obvious merits) to really kick in. Eventually's

best track, a love song called "Angel's Walk" was the kind of perfect marriage of

pop and rock that The Replacements had mastered on Don't Tell A Soul, but it

was an anomaly here. And the album ended with a pointless bit of noodling

("Trumpet Clip") and two ballads that I think I can best describe as "icky." It might

have been a major breakthrough for the permanently cynical Westerberg to come

up with a line like "a good day is any day that you're alive," but that didn't make the

song any better.

Still, there was evidence of some of the old life in the guy. One night, about a year

after 14 Songs came out, I was flipping channels and happened past MTV. I rarely

watch MTV, but when they announced a live performance by Paul, I decided to

stick it out.

Westerberg, looking shabby but a lot less dissolute than the last time I'd seen him, started into "First Glimmer." I rolled my eyes. I particularly hated this song. I remember sitting in a pizza parlor one night and hearing it on their jukebox, and feeling depressed that this thing was getting the push when he'd done so much more memorable work that seemed doomed to oblivion.

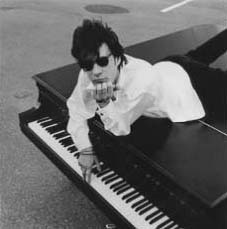

Still I resisted the urge to switch channels. And I got a surprise. Because Westerberg transformed the song... it wasn't that he actually did anything different with it; it was a pretty straightforward reading, and he just stood there, glowering through his sunglasses and swaying his body in that weird way... but somehow, he seemed to pull out of himself depths of real feeling and emotion that elevated this slight-seeming, tepid song into an epic of real emotion. I wish I had it on tape.

He inexplicably threw away a fistful of songs as good as anything in his catalog,

leaving them for b-sides and movie soundtracks. Singles, an awful

twenty-something romance flick, got two pre-14 Songs tracks: "Dyslexic Heart," a

bubblgummish pop-rocker (fans hated it; I loved it) and "Waiting For Somebody,"

a rather ominous rock song that despite its modesty, actually ranks with

Westerberg's best; a close listen to the lyrics reveals a suicide note more chilling and

less melodramatic than the more celebrated "The Ledge" ("I know down deep, I

made a big decision/I'm going to sleep, I'm going it alone"). Among the wretched

art-metal tunes that filled up the soundtrack album (who the hell ever came up with

the idea that Seattle's pseudo Black Sabbath/Led Zeppelin fetish ever amounted to

anything worthwhile?) they shone like diamonds. A weird but amazingly rockin'

cover of Jonathan Edwards' "Sunshine" ended up on the soundtrack album for the

TV series Friends. The weird but fascinating ballad "A Star Is Bored" went to

Melrose Place, and a hilarious cover of Cole Porter's "Let's Do It," done as a

full-throttle punk duet with Joan Jett went to the odd cult film, Tank Girl.

Meanwhile, "Seein' Her," one of his best love songs, "Men Without Ties," an odd

paean to bachelorhood, and "Stain Yer Blood," a great rocker that ranks at the top

the Westerberg heap, all ended up as B-sides. Any of these would have livened up

14 Songs and are far superior to that album's lesser tracks. Maybe he just didn't

want the album to sound too Replacements-like? Or maybe he just had his head up

his ass?

Meanwhile, his 1996 tour saw Westerberg pumping out Replacements classics with

enthusiasm and spirit, and if his crack band (including cult rocker Tommy Keene)

couldn't recreate the magic of the original, at least they were always in tune and in

time, and Westerberg even got all his lyrics right. The show I saw in San Francisco

that fall was celebratory and thrilling, and when he closed the show with a pair of

songs from Sorry Ma, Forgot To Take Out the Trash, it seemed like he'd finally

come to grips with and accepted his past. Unfortunately, when Reprise records

pulled the plug on album promotion due to low sales, Westerberg responded by

pulling the plug on the tour, firing his crack band and heading for home. When next

heard from, he was in disguise as "Grandpa Boy." The single, "I Want My Money

Back" b/w "Undone" on Monolyth was something of a return to form for

Westerberg; the A side a rave-up that showed he hadn't forgotten "Gary's Got A

Boner" (and more power to him), the B a goofy country-rocker that showed he

could still catch that sense of accidental genius (listen for the Dylan parody in the

bridge). A less enthralling EP followed, and while it didn't quite have the charm of

the single, there were highlights: "Lush and Green," a first-rate creepy ballad in the

manner of "Here Comes A Regular," and "Psychopharmacology," which as far as

I'm concerned is a re-write of Eddie Cochran's "Nervous Breakdown." It seems

Westerberg can still turn on the inspiration if he wants to.

Which leads us to the latest, Suicaine Gratification, which finally emerged after

close to a year of being pushed back on the schedule (and even a period in limbo

where it looked like the damn thing would never see the light of day). After a long

period of dire warnings in the newsgroups that Suicaine was nothing more than a

collection of piano ballads and "lite" folk-rock, and his worst work ever, the album's

release has been greeted with hosannas proclaiming it to be his best solo work.

To these ears, it sounds like they're all hearing a different album. Suicaine does

feature a handful of piano ballads, and one countryish tune that sounds a bit like

Wilco, but at least half of its twelve tracks are assuredly rockers, albeit mid-tempo

ones. If anything, this album rocks harder than Eventually, if only because the

guitar sound is a lot dirtier. Unfortunately, after half-a-dozen spins, Suicaine doesn't

seem to be worth getting worked up about too much one way or the other. The

piano ballads are something of a departure, but, with the exception of "Bookmark,"

they're awful, among Westerberg's worst mistakes. Of the rest, mostly they're

pretty much standard-issue Westerberg, love songs and anti-love songs and odes to

insecurity and self-doubt, powered by rough-edged guitar and strong hooks and

clever lyrics. Sometimes you get a surprise: the line "when the loneliest eyes and the

emptiest arms finally decide to meet" (from "Born For Me") slapped me upside the

head the same way earlier such couplets did, back in the day. The performances

definitely seem a lot more heartfelt than on Eventually, which was mostly

bloodless, but he's still running on songcraft, not inspiration.

I have to point out something here. There's nothing wrong with songcraft. The idea

that a songwriter has to write from experience, that his work has to express some

great truth about the state of his mind, or his soul, or his life is a myth. Songcraft

served guys like Willie Dixon, Cole Porter, Otis Blackwell, Eddie Holland, Smokey

Robinson, Dan Penn, the whole Brill Building crowd and many others quite well,

and most of them were better at it than Westerberg, for that matter.

And songcraft is what we're likely to get from now on. If anything is made clear by

Suicaine, it's that The Replacements are dead and gone forever. In interviews,

Westerberg now repudiates his old band, his old music, and even his previous solo

records. He may never tour again, and there are even hints that this might be his last

work for awhile, maybe forever.

Whatever Westerberg decides to do, it won't be The Replacements redux. It was

unfair to ever expect such a thing, anyway. After all, great bands depend on a

certain kind of gestalt. Lou Reed, John Cale, Iggy Pop, John Fogerty, just to name

a few other guiding lights from celebrated bands, all have had long solo careers in

which they failed to reproduce the glories of their former organizations. In fact, the

times any of them tried to, they usually fell flat. Any artistic successes they found

came when they chose to leave the past behind and find an individual voice of their

own. Once that happened, all of them produced work that was different from what

had come before, but not necessarily without merit of its own. And, for better or for

worse, that's what Westerberg has done.

And in that respect, he deserves credit. It would be easy for him to put together a

new batch of stumblebums and crank-out some more wise-ass rock. The results

would almost certainly be enjoyable and possibly even commercially successful in a

way that his solo albums haven't been. Hell, if he really wanted to sell out he could

have done the Chrissie Hynde thing and just gone on as The Replacements with

whoever was willing to play back-up to him.

Instead he's taken the more honorable route, and it's clear by now that

Westerberg's solo albums are what he wanted them to be, and the only way to

judge them fairly is by their own merits, not in comparison with his old band. And if

they happen to be far less inspiring works, it's because that's the choice Westerberg

made for whatever reason, and if you care about Paul Westerberg or his music,

(clearly, I do) you just have to deal with it. All I can say is that, even though I doubt

I'll listen to Suicaine much more than I do Eventually (and that's rarely), and even

though I like the J.B. Hutto album I pulled out of the used-CD bin the same day I

bought Suicaine a lot better than Westerberg's opus (Hawk Squat, on the Delmark

label. First-rate Chicago blues with Elmore James-style slide guitar -- go buy it!),

I'm still not throwing any of Westerberg's solo albums into my reject pile. And I

imagine when the next one appears (if it appears), I'll be there to buy it as soon as it

hits the stands, just like I was for this one.

LINKS:

Kathy's Paul Westerberg page remains is the definitive repository for information on his solo career.

There are several pages devoted to The Replacements, but as far as I'm concerned

the best place to start is The Skyway Mailing List Page.