Wooden Wand

Interview, Part 2 by Addison Martinez

(June 2021)

PSF: It's very cool getting these music references from you because you're such a music lover. I definitely will check out that Skip James biography; sounds like essential reading. While we're talking about the Vanishing Voice, what's the story behind Xiao? What was it like writing with that many players and is there a relation to "Sweet Xiao Lee"?

JJT: For the first few years of WW, which would be the stuff heard on the first few LP's as well as the early cassettes and CDR's, there were two distinct working methods: one was to just write and record songs in the traditional sense, which didn't happen every often but which produced songs like "Dogpaddlin'" and about two-thirds of the Harem of The Sundrum album; the other approach was to build songs from heavily edited improvisations, which is what you hear on Xiao and most of Buck Dharma. I would record impromptu jams and improvisations with various groups of people and then take the music home and add lyrics and melodies. Sometimes, I did the singing live with the band, using a similar approach. I wish I had more opportunities to do that sort of thing now. This was also how I recorded a lot of the stuff in my previous band, Golden Calves: just record everything and then privately edit, overdub, and sculpt songs from it. There were a few times I'd just grab a paperback book I had lying around and open to a page and just read-sing words at random. Or I'd read the words of a sentence backwards, or skip every other word. This allowed me to tap into my subconscious, and I found that melodies flowed pretty easily from there. So, to answer your question, the early days of the band were not really group-oriented, if that makes sense. Often, people would only find out they appeared on a record after I sent them a copy of the LP. This changed around the time just after the release of Buck Dharma--2006 or so--when we started touring and stuff. That's when it became a more traditional band with a more or less fixed membership of the same 5-7 people recording and playing everything.

I think when a lot of people think about the role of the voice in improvised music, they think either of scatting or screaming, but I like the idea of applying the idea of spontaneous vocal composition to more traditional song forms. Most recently, some of the Wooden Wand & The World War IV album was constructed this way.

Most of us do this, by the way, whether we realize it or not. If you've ever sung a silly song to your dog when no one was listening, it's the same idea.

There used to be a guy in Boston who turned up to every WW show I played up there, and he'd always request the song "Spiritual Inmate." I never had the heart to tell him that I only ever played and sang that song one time: the day I recorded it, which is the version on the album. Ditto almost every early Wooden Wand & the Vanishing Voice tune with lyrics and vocals. So, there was no way to actually recreate those tunes. Again, I wish I could do more of that sort of thing because, unlike playing a solo set of songs I've played a hundred times, improvising vocal melodies and lyrics feels like a creative act, and it's really fun.

The running "Xiao" theme, like the "Christ" theme in a lot of the titles, was just a way of creating a sort of mythology by having various threads and recurring characters in songs. This was influenced by bands like Tower Recordings and Gong.

PSF: I've only gotten a taste of the Golden Calves but I was pleased to find out some copies remain of the Money Band+Century Band double LP. This may seem like a smart question, but with song titles like "Seraphim Radar Rallies" and "Calves Heavenward," and the name Golden Calves, were you just being antagonistic in those days? Or were you a young genius of occult knowledge? I can't see the tree that bore Wooden Wand bearing bad fruit.

JJT: I was definitely no young genius! I'm a high school dropout, man. I did attend college, but didn't graduate from there, either. I'm just an autodidact. I get curious about random things and soak up as much information as I can, but I also have a bad memory, so I forget a lot of things, too. I like to reference, in my song titles, things I am reading, watching, or listening to, almost as a way of tracking them. This also, ideally, draws attention to other, greater works of art--an endorsement, you could say--in case a WW fan gets curious and wants to explore on their own. I've learned a lot of things by following similar threads. And like I said, it's a nice way to chart my own obsessions and interests. For instance, "Calves Heavenward" is a reference to the first Amon Duul album, Paradieswärts Düül, which I really liked at the time.

PSF: How long have you been on the road? Is it true WW & the VV were a traveling commune?

JJT: I've been touring since 1997. The second season of my podcast, The Toth Zone, will go into some detail about this period. I think WWVV was a commune only in the sense that any band who tours for more than a week or two together will develop bonds that resemble the sort of collectivist spirit you find in any tight knit pack. But we were always very happy to return to our own homes and our own beds at the end of tour!

PSF: Alright, I'm not sure if I need a response to this, but I missed your email stating that you wrote "Ragtop Ruby," not Woody Allen. Is that correct?

JJT: Yeah, the only thing I borrowed from Woody was the title of the album Wither Thou Goest, Cretin.

PSF: Do you use a pick?

JJT: Sometimes. It really depends on the song. I really like the sound of strumming without a pick, using just the backs of my fingers; there's less attack that way, and it allows my playing to be a little more dynamic, I think, if not as precise. For 111H, I use a pick most of the time, unless I'm doing fingerpicking, of course. Some of those parts are a little more intricate so I need the control of the pick to play them right.

PSF: For all those who were lucky enough to make it to the shows, will you tell me about "Eagle Claw"?

JJT: I actually don't remember much about writing that song. I do remember I had it mostly written but lacked a title, and then I noticed a fishing pole leaning against the wall. Brand name? Eagle Claw.

PSF: Your lyrics are full of practical wisdom. What would you say has been your greatest education in life?

JJT: Maybe it sounds shallow but, beyond just being unafraid to travel and willing to be uncomfortable sometimes, music has been my primary education. Pat Metheny refers to this idea of "progressive education," which I understand as the idea that one art form can lead to others. I can't even tell you how many films I have seen or books I have read because a song I liked referenced it, or an artist I admired talked about it in an interview. Iron Maiden made me want to watch The Loneliness of a Long Distance Runner and read Dune when I was a mere 12 years old.

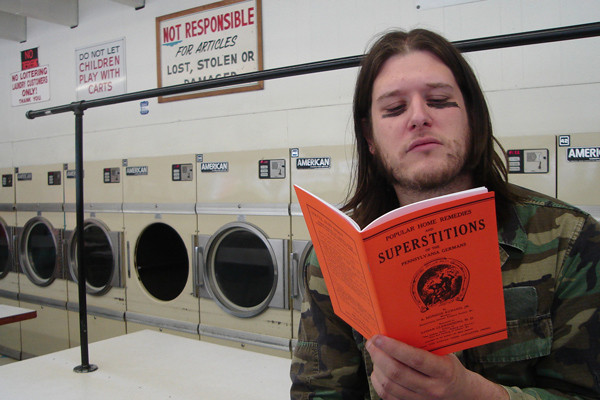

As for practical wisdom, the recurring theme I see running through a lot of my songs--and I only became aware of this thread a few years ago--is the idea of a silver lining. Everything's terrible, but, hey, that beer sure tasted good. If I'd checked out yesterday, I wouldn't have experienced that. I think you'll find this notion of the One Good Thing To Keep You Going running through a lot of my songs. "Sometimes you just gotta stop and consider the good things / like how your money don't get ruined when it gets washed in the pockets of your jeans" ("Winter in Kentucky"). I mean, someone had the foresight to design currency that way: to use not paper but linen and cotton, which doesn't absorb water the way paper does. They could have just used regular paper, and if you left a $20 in your pocket when you washed your jeans, well, you'd be out twenty bucks. I'm quite sure they were not thinking about, err, washing machines when they invented banknotes in the 11th century or whenever it was, but someone, somewhere instinctively knew it should be relatively waterproof. Shit like that blows my mind.

PSF: Have you ever considered yourself a poet? Do you write poetry, or is it always coming with music?

JJT: I wrote poetry when I was very young, before I realized that I had very little talent for it. I still write an average of one poem every year or two, when I get the notion, but I never show them to anyone.

To me, poetry and songwriting are totally separate disciplines. Most great songs don't read so well on the page, and in my experience, most poetry "adapted" to music doesn't really work (though there are a few exceptions).

PSF: You've mentioned the concept of "self-deliverance" before. What do you mean by that?

JJT: Suicide. The great philosophical paradox. I've lost quite a few friends this way and I am no closer to making peace with it.

PSF: Is that what "Aurora" is about?

JJT: "Aurora" does touch on the theme of sudden and unexpected death, but not necessarily suicide. Like a lot of my tunes, it's about wasted time. Aurora being the morning, the best time of the day, the time when everything feels possible. Pity then to spend that time drowning your eyes in a screen.

I'm obsessed with time. It's probably a little unhealthy.

PSF: What's your favorite song about time?

JJT: Great question! "Tick Tock" by Death in June. It makes me feel anxious, which is how time makes me feel. But also "Beat the Clock" by Sparks; that's one to aspire to. Both great songs.

PSF: Your instrumentals on Bandcamp have a way of making time fly. I thought I was six (maybe eight) minutes into "Lucifer Over Lambeau (Collage 165.3)" and when I looked at my player, over eighteen minutes had passed. I also wished "Kilim" and "Pilgrim" could have gone on forever when I heard them. Who and what has influenced your instrumentals?

JJT: Thank you. The bending of time is one of the intended effects of that music, so I'm happy you experienced it that way. "Lucifer Over Lambeau" is a collage of private sound-based work dating back several years, influenced by musique concrete, tape music, and abstract drone. I was under the spell of people like Roland Kayn, Tod Dockstader, and David Jackman, not to mention Harry Partch's irreverent approach to acoustic-based music and some of Giacinto Scelsi's choral work. The piece features a homemade instrument, invented and designed by my friend Forrest Marquise, called an octatone, which is similar to a hurdy-gurdy. This strange instrument is endlessly inspiring. In another life, this will be the only instrument I play. It's a deceptively simple tool, but there is a lifetime of possibility contained in it.

"Kilim" / "Pilgrim" takes a similar approach, but focuses less on concrete blocks of sound and more on the textures and tonality of Appalachian and Cajun music. I liked the idea of stretching those beautiful fiddle sounds, in particular, into infinity. I don't play the fiddle (though I wish I did) so sampling, treating, and stretching the eerie, keening sounds I loved was the closest I could come to realizing this idea. I also added some banjo (an instrument I do play, albeit poorly), mountain dulcimer, and other sounds to make it feel less impersonal, and to avoid mere appropriation. The inspiration here was Delma Lachney, the mysterious Harisis Group, Henry Flynt, and a whole lot of pre-war hillbilly music.

PSF: Has the pandemic effected your work?

JJT: The pandemic has forced me to work exclusively in isolation, which naturally affects the music I make. I have always been relatively comfortable working alone, but I prefer to mediate this with collaboration, which helps to create a balance. Not collaborating with people in person has been more difficult for me than I could have imagined.

PSF: One Eleven Heavy just had the honor of having a strain of cannabis named after the group. Have you had the honor of trying it?

JJT: I have not tried the 111H weed, unfortunately, as I think it's only available in Northern California. That was quite an honor, though, to have a strain named after your band. Even my mom was impressed!

PSF: 111H have a way of transcending styles as a rock band. In Dylan's book, he described Lynyrd Skynyrd as being "sidewinding" and I can't help but think the same of 111H. Is there a general ambience that the group goes for?

JJT: Though we are, like most bands, the sum of our influences, One Eleven Heavy is very much a rock band in the traditional sense. When Nick and I first conceptualized the group, we spoke about our personal "rock Mt Rushmore." This was, for us: Crazy Horse, the Dead, the Stones, and Royal Trux. Beyond that, Nick is deeply into a lot of Spanish and Latin American psych rock, as well as a lot of obscure folk rock like The Youngbloods, and is a Parliament/Funkadelic freak. Dan is a big jazz head, knows a lot about metal, and is the only guy I know who can speak with equal expertise about both Albert Ayler and Black Oak Arkansas. Hans is steeped in New Orleans music and blues and is a Nicky Hopkins nut. And all three drummers we've had have been equally omnivorous; I remember Jake playing a lot of Quiet Storm jams in the van on our last tour! So, these influences tend to marinate. That said, we're also careful to not lose sight of our initial concept: to make modern music that adheres to the rock and roll tradition, played with zero irony (this is important), while sidestepping some of the lyrical and social trappings that make rock and roll ridiculous and anachronistic.

It's far too easy to listen to a Sun Ra record and then go and try to make a version of your own. Consistency is important, and as a result, despite being a band of voracious music fans, we don't follow our every creative whim or impulse, as much as we'd occasionally like to. But sometimes the non-rock 'n' roll stuff comes out in the music in a natural way, and we honor that.

PSF: You've said you could write a book about the Waiting in Vain sessions. Can you tell us a story you haven't yet told about recording that album?

JJT: There have been a few times I just gave myself over to the idea of being 'produced.' I've done enough home recording to be intimately familiar with my own aesthetic, which can often mean relying on tried and true habits. So, when I made albums like Death Seat and Waiting in Vain, I did a lot of deferring.

I like parts of Waiting in Vain, but I would agree with some of the criticism I have heard about it: that it doesn't always sound like me. There's a good reason for this: I wasn't always present, and that is the only record I have ever made where that was true, where I wasn't there from the very first basic track to the final mixdown, micromanaging. There were so many talented and creative people involved with that record, at some point I just felt like my own instincts would have gotten in the way. And there was (to me) a lot of money on the line and a lot of expectation, so I started to feel like my job was to just write the songs and let everyone else turn it into a record people might want to buy.

So, my memories of that record are of quickly teaching people the original (simple) guitar and vocal parts, and then gallivanting off to Amoeba or Aquarius to buy records while overdubs were happening back at the studio. I also remember hanging out in the Tiny Telephone studio lounge a lot, getting high and watching Aqua Team Hunger Force (a show I had never watched before and have not seen since) while major parts of the record were being recorded in the other room. It wasn't that I was checked out or not invested; it was a strategic approach to absent myself. But that meant a lot of things were done that I might not have done (like spending half a day on handclap overdubs). There are several songs on that record on which I do not even play guitar.

Then there was also the business side of that time period, which was pretty confusing and fraught. I'd never been the subject of a label bidding war before, and in retrospect, of the three labels who wanted to release that record, I think Rykodisc was probably not the best choice, given the way things turned out. But as Alanis sang: you live, you learn.

PSF: I think Waiting in Vain is an excellent album, but I agree there is something different about it and now that you mention not playing guitar on every track, it makes sense. The songs are all there and the vocals sound great, but there's a ragged quality in the Wooden Wand records that's missing from Waiting in Vain. I also think titling it Becoming Faust would have added a level of intrigue to the work. "Poison Oak" is just about perfect in every way though -- it's like you're an obsessive beast with righteous indignation, and the music is meticulous and sympathetic. Doesn't sound like Wooden Wand, but that doesn't hurt it either.

JJT: I'm glad you like it! The people who like it seem to really like it. I haven't heard it in over ten years.

PSF: Were you happy with the making of James and the Quiet?

JJT: I wouldn't say it's my favorite WW album as far as the songs go, but the experience of recording it was totally positive, and I had a great time working with Lee Ranaldo, who I love dearly. I was--and am--a tremendous SY fan and Lee's songs were often my favorites, so working with him in such a close capacity was a thrill. I sorta warned the band going in: "Now, listen, let's not eat up any more of Lee's time than we need to." But Lee quickly went from merely producing the record to being an active collaborator, and the album is all the better for it. He'd be like "Hmmm. Guys, I wanna try something. Gimme an hour to work on this crazy idea I have." And he'd just experiment with a guitar or vocal part or a weird effect or something. He was just totally invested in the project, which also had the effect of making me feel like the songs were worthy of the time we were putting in. I do not have a single bad thing to say about Lee Ranaldo.

The album's probably three songs too long though.

PSF: I'd like to know if you have any preference or fond memories of '90's radio. I know you were into metal and hip hop; you're about 9 years older than me, so you probably have a much different perspective on the music of the day. I still don't know what alternative really means -- for you, it may have been Nirvana, for me, it was Marcy Playground, the Verve Pipe, Matchbox 20. I hear Wooden Wand songs --like "Dirty Penny"-- transcend jangly folk and --like "When Your Stepfather Dies"-- transcend your usual waltz in a way that makes me think alternative, which is, to me, an accomplishment, if nothing else. I think of you as a bastion of the alternative sound, one of the last cats who could play that shit. Was there anything in that pop/rock field that affected you in those days, or since those days?

JJT: Well, my entire teenage life took place in the '90's (roughly age 12-22), so that was a pivotal time, and a lot of popular music from that era seeped in, and a lot of that music was so-called 'alt rock.' As for underground stuff, the genre retrospectively known as 'screamo' made a big impact on me, specifically bands like Universal Order of Armageddon, Antioch Arrow, Moss Icon, Heroin, and Angel Hair. I was also obsessed with hip-hop and British indie, and was just starting to discover techno. But I was definitely not immune to the siren song of bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and (especially) Smashing Pumpkins. I still really love Siamese Dream.

In general, though, as far as mainstream music goes, I vastly prefer the '80's to the '90's. There's no contest, especially when you consider that the 80s weren't merely about synth pop (though synth pop is one of the major reasons I love 80s music). A decade that could give us the Pet Shop Boys and Erasure, Cyndi Lauper and Madonna, and the Replacements and Black Flag? Plus, legacy artists like Peter Gabriel, Steve Winwood, and Robert Palmer doing what is arguably some of their best work? Astonishing. Tremendous leaps in terms of technology, production, creativity, visual aesthetics. Even pop radio was avant-garde and experimental. When I think of the '90's, very broadly speaking, I definitely don't think of any of those things. In many ways, it was a disappointingly regressive decade for music compared to the '80's. OK, rant over!

PSF: I have to drain you of more music-knowledge. Did Horace Andy record any LP's at Studio One, or just singles?

JJT: Skylarking! But a lot of the early singles he recorded (and their dubs) have trickled out on numerous compilations. Not Studio One, but the album In the Light coupled with the dubs (reissued a few years ago on Blood and Fire) is another one you should absolutely hear.

PSF: I really love the Wooden Wand song "Guru Femmes" and I can tell you think fondly of California in "Ellwood Mesa." I'd like to know what it was like for you, as a New Yorker, to reach the West Coast for the first time. For me, coming from Georgia, it was the first place I actually felt like a country-bumpkin and also, welcome in the world for being so. So, I'm wondering if you had any sort of A-to-Z experience coming from the East Coast as well.

JJT: I think the West is easy to romanticize. Obviously, it's a very seductive place, in every sense of the word. It's not surprising that people of a certain temperament are drawn to it. I don't remember the first time I traveled out West, but I think my first impression was probably like that of a lot of East Coast people when they first arrive: "this is where I belong." The Germans have a word for this feeling, of course: heimat. The best way to describe the feeling to an English speaker, or so I have been told by a German friend, is "not your home or your hometown, but the place you feel most at home; your ultimate comfort zone; the place you'd want your ashes scattered when you die." Unfortunately, I've been informed it's also a problematic word in Germany, with some very negative connotations.

And yeah, I have a lot of affection for certain parts of California. I've recorded several albums out there and have spent a lot of time in L.A. and San Francisco. And, yes, Ellwood Mesa, in Goleta, is one of the most idyllic places I've ever been. But I've known a lot of people from the East Coast who had that heimat feeling initially who moved out West and lasted a few years and then went back East. They couldn't hack it. The older I get, the more I recognize that mine is a very East Coast sensibility (which may just mean I'm uptight - ha ha ha!). There are mundane reasons I don't think I could survive out West, too: I'm not sure I could deal with having to drive everywhere I want to go, and I'm not sure I'd be able to tolerate the West Coast's, err, flexible definition of "on time." Lateness is a big pet peeve of mine. Like I said, uptight. But I'm 42 years old and I've resigned myself to this aspect of my personality. My exes and the members of any band I've ever been in will tell you, likely with a groan: to me, "early" is "on time" and "on time" is "late." Any later than "on time" and I might not be there when you arrive. Because of this, I'd probably not last a week living out West.

I sure do love the weather out there, though.

PSF: You wrote "One Can Only Love" and "One Can't Only Love" and have stated that you're not sure which side you're on. I'd love to help you figure this out, but the topic is so deep that I can only get as far as to remember the phrase is "One can only guess." Are you any closer to choosing a side since you released these songs?

JJT: Hmmm. A good question. Maybe those sentiments aren't mutually exclusive.

"One Can Only Love" is indeed posited in the song, as you suggest, like "one can only guess." Maybe there should be a 'shrugging' emoticon accompanying the title. Like, if all else fails, you can always exercise compassion. I do believe in empathy. One of the many reasons social media is so poisonous is it strips us of our empathy; your fellow human beings become avatars on a screen, which makes assassinating a person's character as easy to do as killing a bunch of monsters in a video game or whatever. My daily interactions with actual human beings are almost uniformly positive, but on those increasingly rare occasions I check in on social media, I just want to crawl back into bed. This cognitive dissonance can become really confusing over time, and it can make you cynical. I'm generally wary of reductive, broadly sanctimonious proclamations, but I really do feel, at base level, that it's never a mistake to try to love your fellow citizen, and to give everyone you interact with the benefit of the doubt. It's basic golden rule shit. I think what I am trying to say in that song is, if you can do nothing else, at least try to love, because with love comes understanding, and with understanding comes empathy.

"One Can't Only Love" is more about not forfeiting your identity for the sake of another person. I think, in general, there are far too many love songs. There have been many, many great ones, but the majority of them are silly, naive, or trite. The tune you refer to is a kind of sister song to my other song "Don't Let Love Make A Liar Out of You" which more explicitly criticizes the banality of the modern love song, hopefully in a way that some will find humorous. Loving and being loved are important, possibly vital, components of the human experience, but one can't only love. Try to do something that makes you worth loving, maybe, or that better allows you to love yourself. You know?