ANNE WALDMAN

The Vocal Body

interview by Glenn Morrow

(April 2014)

The poet Anne Waldman is well known as the founder (along with Allen Ginsberg) of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University. For many years, she also ran the St. Mark's poetry space. With her son, the musician Ambrose Bye she has a record label (http://www.fastspeakingmusic.com) that releases spoken word work with musical accompaniment. As a poet, she has published over 40 books including The Iovis Trilogy, a nearly thousand page epic poem. Born in New York City in 1945, she splits her time between a family apartment in Greenwich Village and Boulder, Colorado.

Outrider, a documentary about her life and work is currently being assembled. The title refers to the Outrider movement which, if I understand it correctly, posits the idea that there is a tribe of poets and artists that move parallel to the mainstream culture, not outsiders but a group that creates a discourse out on the edges where interesting things often happen. I can imagine these outriders performing daring raids into the American corporate landscape they ride alongside, plundering what they need before heading back to the outskirts.

This interview transpired between two of her performances in two very different New York venues. The first one was at the Rodeo Bar, at a musical tribute to the late Lou Reed, where Anne took on a noisy barroom crowd with an impressive poem that conjured up the power of the Velvet Underground. She also sang the campy VU obscurity “I'm Sticking With You." A few months later, she performed to a pin drop quiet house of poetry enthusiasts at the Zinc Bar, a jazz club that hosts Segue, a poetry series that has been running at various venues for 25 years.

She is a spoken word poet of the highest order, a true entertainer and a fierce reader with a lifetime of technique that brings the printed word alive; she employs everything from chants, gesticulation, song fragments and foreign languages when she reads. She is confident enough to let a word like “exegesis" roll elegantly off her tongue before breaking text down into bits of raw sound, firing off packs of raw consonants into stuttering guttural noises, practically speaking in tongues, doing whatever is required to get the piece across.

ED NOTE: the author here happens to be the head honcho at the incredible Bar/None Record label

PSF: You are a poet who seems especially interested in performance as well as the intersection of words and music. You don't just leave the poem on the page. Do you see poetry and music as operating in different spheres so to speak? What are your thoughts on how they can and should be combined?

AW: As I see it, (they're) complementary spheres that jump their frames at times. The poet needs to be reading other poetries from all times and place and studying old dusty tomes and shiny new information sites. Playing music and humming along as she goes about this. And pursuing investigative and documentary poetics. I write books, I write voluminous books with deep attention to the page and the structure of language on the page. But I also see places always within the writing where I have to burst into vocalization and song and performance which is ancient to poetry... and I love this. The energy for that can't be contained. And there are also pieces that are composed specifically “on the tongue" as Allen Ginsberg used to say, with specific modal structures in mind. And these “sound" inside me, clamoring to get out. I work solo and also enjoy collaborative projects in the studio, as well as improvisation with a range of musicians and in performance. Musicians are angels. Within my 1,000 page dense epic: The Iovis Trilogy: Colors in the Mechanism of Concealment there are places that are enhanced by orality. And because I live around music-makers my son Ambrose Bye, and nephew Devin Waldman, the opportunities for collaboration and trying out musical ideas out is endless. It's a happy marriage, music and poetry.

PSF: You seem very comfortable and downright fearless on a stage. I saw you take on a crowd from the floor of a noisy barroom. Do you consider yourself a confident performer?

AW: Thank you. “Fearless" is a compliment. Confidence grows over time. There are always some people listening and curious in that noisy barroom and I've been on the other side of that as well, listening to poets I really wanted to hear from with the annoying background of boisterous chatter and rattling dishes and even heckling. I grew up in Greenwich Village and spent time in folk clubs, and in other venues listening to great artists like Dave Van Ronk and Nina Simone in non-concert settings. There was a poetry series for years at a place called the “Ear Inn" (The B on the sign was worn down and became E and people were extremely noisy especially if there was a football game on.) It always seemed ironic that it was designated “Ear" because it seemed so “earless." Yet it was one of the most sophisticated places for poetry in town. I guess I'm confident that there's always someone out there listening. There's a great Buddhist slogan: gateways are numberless, I vow to enter every one of them.

PSF: Where did you grow up and what was the earliest music you were exposed to as a child?

AW: I sat on Leadbelly's knee as a wee babe in what is now my own living room! He was a friend of the occupant at the time... And I went to hootenannies in the neighborhood where Peter Seeger held forth. And I had piano lessons and was involved with productions at the Greenwich House Children's Theatre where we would tell the story of America through song. “Tenting Tonight on the Old Campground," “If I Had A Hammer"... My older brother was a “folkie" so there was a lot of that very special music around. Harry Smith's folk anthology...My father would turn on the radio for the Met Opera broadcasts. He had been a swing piano player in his youth. Jazz was important – my mother had Cecil Taylor's first album. Wide ranging, ecletic. I sang in a church choir at one point.

PSF: In your teenage years what kind of popular music caught your fancy and stole it's way into your heart?

AW: Chuck Berry, Everly Brothers (“Dream Dream Dream)" Sam Cooke, Johnnie Ray, Peggy Lee (“Fever"), Ray Charles, Buddy Holly, Elvis to name a few. Thank goodness for late night radio as a teenager. It mollified the existential angst.

PSF:Do you think music can have an epiphanic effect on a listener and if so can you give some examples of this in your own life?

AW: Certainly, and how wondrous that is. John Cage who made you listen to amplified cactus needles. Om Kalsoum, the Great Egyptian Mother Goddess, a transmission of eternal unconditional embrace. I was in a cab with an Egyptian cab driver who told me there's a station in Egypt that plays Om Kalsoum 24 hours a day. I would hope that still goes on with all their political trauma and suffering; that would be merciful. Bob Dylan's live shamanic performances in whiteface during the Rolling Thunder Revue, a caravan I travelled with. The panoramic awareness of “The Streets of Rome," and “Idiot Wind." The Magic Flute and Parsifal. “Symphony for the Devil."

PSF: You had an early fascination with the poetry and writings of the Beats. How were you first exposed to them and was there a musical soundtrack in the background?

AW: I was first exposed through the written texts, small press adventures. And you could always hear them off the page in your own head. City Lights Pocket Poets, later Donald Allen's anthology of The New American Poetry. We browsed and shopped at the Eighth Street Bookshop on Macdougal Street that was also publishing Totem/Corinth books. I met Diane di Prima when I was 17. And David Amram. I went to the Berkeley Poetry Conference in 1965 and encountered Allen and Charles Olson and Ed Dorn there, as well as Ted Berrigan and Ed Sanders, and Lenore Kandel. I heard recordings of Kerouac with jazz.

PSF: The poem your read about Lou Reed at a recent tribute show (Rodeo Bar, November 2013) really got to the essence of the man's music. It was impressive how you evoked the feedback and driving rock n roll power of the Velvet Underground in your poem. Is that poem published anywhere?

AW: There will be a printed version from the Harry Smith print shop at the Kerouac School at Naropa soon and there's another part of it I didn't read that night that may be found on the site: loureed.com/inmemoriam.

PSF:You did some theatre with some of the Warhol superstars. Did you spend any time around the VU and the Factory crowd?

AW: Yes, I spent time at the Factory and was close to Gerard Malanga, and Rene Ricard, Jackie Curtis, and Brigid Polk. And Andy and Lou as well and Paul Morrisey and others came to my apartment (shared with Lewis Warsh) at 33 St Mark's but I was also busy keeping the world safe for poetry at The Poetry Project which was in a parallel yet just as demanding and critical universe. But things weren't so compartmentalized back then- poetry, film, performance music worlds, theatre, dance shared affinities and information. We hung out at Max's Kansas City together. It was a political time as well. Kenward Elmslie and I performed with the Palm Casino review. And Candy Darling and Jackie were among the other performers and most memorable presences. One evening, Kenward and I wore penguin suits; I can't imagine why. We performed mostly in tuxedos. Kenward is a brilliant songwriter. I did a great torch funny song of his -“One Night Stand" - “kisses like fire, profile nice but big rubber tire, tends to use the verb ‘enthuse,' one night stand! Keep it a one night stand!"

PSF: You were invited to be the poet in residence on Dylan's Rolling Thunder Review in 1975. How did that come about? What work came out of that experience and how did that affect your own relationship with music? In recent years, Dylan has been known to be

reclusive on tour but was he engaging the traveling community he had surrounded himself with at that time? How did Dylan deal with a poet in residence?

AW: I met Bob first through Allen when Allen was recording at Electric Ladyland and yes the ethos of Rolling Thunder was generous; lots of people were coming on board. We would pull into town almost serendipitously and amp up the energy and mix with the crowds and then be off into the night.

A magical progression. And the concerts were powerful. Bob was inclusive, and I was consulted and included in the “Renaldo and Clara" project. And supported and fed and housed and paid for two minutes of reading my poem “Fast Speaking Woman" on the soundtrack. There was something utopic about this moving body of energy and all its brilliant artists and cross-fertilization. I wrote a text entitled “Shaman Hisses You Slide Into The Night," you might find in a bi-lingual edition through Apartment Editions (as Shaman/Shamane) in Hannover, Germany.

Bob Dylan had something to teach poets about the mouthing of the syllables. You could always hear his lyrics. I appreciated his use of violin and mandolin during that Desire period that set up a certain ambience for those songs. It was the dynamics of performance that was most adhesive for me, the public ritual and catharsis. How the energy shifted night to night, how big and yet how intimate it was.

PSF:When did you first start performing poetry with musical accompaniment?

AW: Quite early on. But I always thought of my own voice as an instrument. Some old reel to reel tapes recently surfaced where I am trying something out vocally. We couldn't figure out whose voice this was. And I had studied briefly with La Monte Young in the early ‘70's. My voice got deeper and more resonant after motherhood in 1980. And then I started singing more regularly at Naropa, whien we started the school in 1974. I worked a lot with Steven Taylor (of the Fugs) who was Allen's principal accompanist. Jerry Granelli the drummer was at Naropa in the early days. Don Cherry as well. Art Lande later. Mark Miller with shahuhachi. I knew Steve Lacy as a teenager (he had married my brother's first wife), and we performed a few times in Italy with his partner, the wonderful singer Irene Aebi, and at Naropa. I would join in when I travelled with Allen on his Blake songs. I worked with musicians encountered locally at reading gigs all over the country, some time with lead time but more often on the spot. And many more instances and occasions I am forgetting.

Playing in a gamelan orchestra at Naropa and in Bali was useful, inspiring. There's something very satisfying about being part of a larger inter-locking and circular musical structures.

PSF: How did making music with your family members come about?

AW: It happened quite organically. My son Ambrose was already attuned to my style and rhythms and delivery (he's always telling me to tone it down!). He started piano lessons when he was eight years old and he lived in Bali with me for two separate semesters when I was running a Naropa program there and was naturally a very good gamelan player. And we were students of gamelan together. He grew up at the Kerouac School and was keyed into poetry from hearing it orally – and listening to Amiri Baraka who he loved, and so many others. After graduating from the University of California in Santa Cruz where he had started creating various soundscapes with his keyboard, he spent a year training at the Pyramind Studio learning how to work the machines and computer programs. Our projects started somewhere in there and became recordings at first, before we started performing. But It's been over ten years now of albums such as Matching Half with Akilah Oliver, and The Mile of Universal Kindness and we have more projects in the works. Ambrose just finished mixing a compilation with my poetry and Thurston Moore and Daniel Carter and Devin all playing entitled Oasis at Biskra. It's for a small company in Belgium by the name of “Taping Policies," a limited edition cassette. And we'll be performing with Thurston in Brussels in June. (June 17th, fiEstival)

And we have our burgeoning Fast Speaking Music label for poetry and music. Devin Brahja Waldman, my nephew, is a serious and passionate sax player and composer. We started working together when he was in grade school. He accompanied me on some readings in Albany and at Town Hall for Bob Dylan's 60th birthday concert on a saxophone version of “Masters of War" and got a mention in the NY Times. That seemed auspicious. He's been living in Montreal and is very active on the music scene there and moving back to New York soon to further expand the horizons. There is a nice exchange in the jazz world with those two cities. He already has three fine albums, the last one produced by Fast Speaking Music, titled “Say Hello To Anyone I Know" and recorded and mixed by Ambrose. (The) cover is a Patti Smith drawing. And terrific musicians Daniel Carter, Daniel Levin, and Satoshi Takeisi. His father, my brother Carl, also plays music. And Ambrose's father Reed is also a poet and singer who writes Buddhist country songs.

PSF: I've always loved gamelan music. You can really get lost (and found) inside the scales and chords. Have you used the instrument for accompaniment to spoken word?

AW: Ambrose performed on a single gamelan metallophone instrument - the kantiilan I believe (upper register) at Naropa during a recent summer performance. It was for a part of the Gossamurmur project. But this is not something one does traditionally - extract a single instrument from the ensemble. Gamelan is a set of instruments, as you must know, and then you have pairings (male and female) of the various metallophones. I love the dynamics of the rich sound too. All the cyclic waves. We studied gong kebyar and I played the jejogan - the simplest cycle possible. But we will probably incorporate more of that sound into some current recordings.

PSF: Can you talk about what you've learned from working with other musical collaborators?

AW: Learned to listen, to follow outrageous trajectories of others' wild sound and trust all the voices inside myself as well. And not get lazy with the words.

In addition, I am working on a project with the composer David T. Little, writing a libretto entitled “Artaud In the Black Lodge" and part of a longer text was used in Douglas Dunn's recent “Aubade" and performed by Steven Taylor who was the composer and director. I am not performing myself here and that is interesting too. And I watched Judith Malina and the Living Theatre turn my play “Red Noir" into a musical -entirely vocal – theatre piece. And from this I learn that there may be many variations around text and sound and I don't have to “own" or control all of them related to my own poetry.

I am currently working with Ha-Yang Kim who is a very intense cello player. I am often astonished by her fierce, ecstatic sound which teaches me something about guts and wind and wood and a far-back ancestral (perhaps) command. I am working on my low breath tones to match hers.

PSF: Can you talk a little about the way the Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics functions? How is it sustained? I was very moved by the idea of a 100 year plan to lay down a tradition for future poets to discover. How real and thought out is that plan?

AW: Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado is sustained by a sense of the world needing a Buddhist-inspired non-competitive contemplative zone to study and hone one's craft and serve the troubled world. And it is tuition driven. The Jack Kerouac School – which is Naropa's creative writing department - has an illustrious lineage and pedagogy and offers fully credited BA and MFA degrees in writing and poetics. It's a unique position for a creative program since we didn't arise out of an English Literature Department. We invented our own “academy of the future" (a line from poet John Ashbery) ourselves and we are now in our glorious 40th year or poetics and cultural activism!

There is quite a bit of history out there and anthologies I've edited and presses generated by the Naropa cadres, and historical archival tapes you can access online (go to Archive.org and scroll down to Naropa or Penn Sound). The year-round MFA degree program is offering fellowships now and a very exciting curriculum. The Summer Writing Program which takes place for a month each year is part of the degree but is also available to non-degree students. We have many guest faculty which includes musicians such as Steven Taylor, Thurston Moore, Marty Erlich, Ambrose Bye, Hal Wilner, Laurie Anderson. Meredith Monk will be present this summer. There are other schools as well under Naropa's umbrella: Religious Studies where Tibetan and Sanskrit are taught, Art, Music, Psychology, Transpersonal Therapy, Environmental Studies and so much more... The theme for this summer's program is Welcome to the Anthropocene.

Nothing in our geologic age not messed up down here by Man, alas.

PSF: You've been involved with the Poetry Project at St. Mark's Church. Musician/poets like Richard “Hell" Myers. Lou Reed, Patti Smith and Thurston Moore have all read there. For lack of a better term is there a rock ‘n' roll connection there? Also how has the Poetry Project evolved in the last four plus decades?

AW: Yes, there always has been a rock ‘n' roll connection I'd say from the start and that continues at Naropa. Don't forget Jim Carroll who at 16 was working at the Project, helping put up the chairs and pass the hat. Ed Sanders and the Fugs.

I always experienced these as fluid zones – these autonomous centers for poetry and performance - great rhizomic zones of endless hybridic possibilities. Poetry has been crucial to rock ‘n' roll lyrics forever and the gestalt of poet is the highest honor. Poets used to be shamans and that what's rock poets are capable of being because they have a great public magnetism that can reach into people's psyches and pull them back from the brink. When I was recently sick with what I felt to be a serious illness, I started singing and dancing with Patti Smith's “Ghost Dance." And later Lenny Kaye gave me permission to record it with Thurston and Ambrose. It's up on the web under Ecstatic Peace. I felt singing that song empowered me to stay alive.

The Poetry Project keeps morphing yet keeps a very special loyalty to poetry- and community – and collaboration and cross fertilization. It's not easy surviving in these times, as you can imagine. The New Years Day event is extremely inclusive of all kinds of music and dance and certainly holds a candle for rock ‘n' roll.

PSF: You've read and sung over many types of music over the years. I've heard you accompanied by jazz players, electronic loops, acoustic guitars and most recently the

“free rock" noise guitar of Thurston Moore. How has your approach to performance evolved over the years?

AW: It just keeps moving with every encounter. I want to keep working on the Ezra Pound opera “Cyborg on the Zattere" with Steven Taylor. I am working with some folks- the brilliant Andrew Whitman of Broken Social up in Canada.I love being challenged by the genius of Thurston, as he is already so evolved as a musician himself. And he writes poetry and lives and breathes poetry and is a major archivist of poetry as well. And Ambrose is key to a kind of stability for he knows my sound instinctively since the womb. So it's a continually generative process that's also fed by these demanding writing projects. Like the recent Gossamurmur and the forthcoming Jaguar Harmonics. I seem unable to write discrete poems so I compose “books," yet within these books are the seeds of song, fractured light and shadow where the words break free directly out of the vocal body.

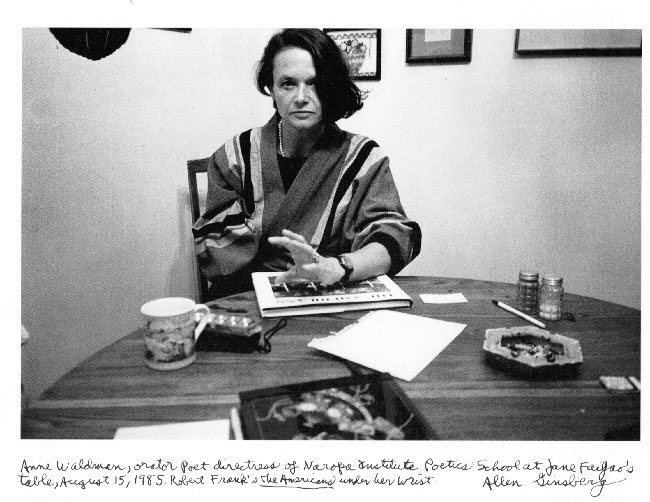

Photo by Allen Ginsberg, © Allen Ginsberg, LLC.

"Anne Waldman, orator Poet directress of Naropa Institute Poetics School at Jane Faigao's table, August 15, 1985. Robert Frank's "The Americans" under her wrist."

www.annewaldman.org

fastspeakingmusic.com