Klosterman Appropriation Project

by Jesse Jarnow

(February 2007)

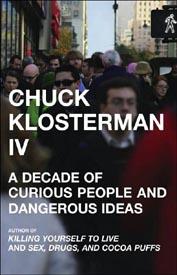

1.Though the title of Chuck Klosterman IV plays on Led Zeppelin's fourth LP (or perhaps Chicago's), the rawk-culturalist's latest is more akin to a necessary singles anthology than a masterpiece of its own. Even so, the decade-spanning CKIV isn't without its own double-gatefold hook, sorting the 34-year old Midwesterner's writing into the surprisingly effective bins of "Things That Are True" (features, profiles), "Things That Might Be True" (columns, rants), and "Things That Are Not True At All" (a long short story).

Through his three levels of truthiness, Klosterman's aw-shucks voice rarely wavers, and sustains through the succession of progressively larger outlets, from the Fargo Forum to SPIN to Esquire, GQ, the New York Times Magazine, and beyond. Even when reppin' for the Mingist of the MSM, Klosterman remains affable: our man on the inside. "Britney Spears is the most famous person I've ever interviewed," he preludes his lead-off profile (from Esquire), sounding like the guy next to you on the couch at the party. "She was also the weirdest. I assume this is not a coincidence." Nor is it one that Klosterman points it out.

Throughout his observational reportage, Klosterman wears the role of Dude rather well -- exactly what made his heartland mëtäl mëmöïr. Fargo Rock City, so genuinely page-turning. A champion navel-gazer and infectious pop stylist in his full-length works, Klosterman's journalism is charmingly nerdy. In CKIV, his gee-whizzing remains infectious, mostly because what he is gee-whizzing really is kinda out there: Bono giving teenage autograph seekers a lift downtown in his Maserati ("Is this guy for real?"), Val Kilmer owning bison ("I just like to look at them," reads Kilmer's quote in the lede), a bunch of goth kids on the loose in the Magic Kingdom (self-explanatory).

Though he has been accused of deliberately playing the part of the "'authentic'" North Dakota hick -- most notably in a front page New York Press character assassination by Mark Ames ("a metaphor for everything vile in my generation"), Klosterman seems just the guy for the job when assigned to describe things that are true. CKIV's introduction, a parable framed by junior high school basketball, begins thusly: "'Can I tell you something weird?' he asked. This probably isn't a valid question, because one can never say no to such an inquiry," Klosterman adds, and is not only right, but describing his template.

These, Klosterman's most memorable stories, are also the type that have what might be called plots -- or, at any rate, sequential events Klosterman can hang his observations from. In the already-classic "1,400 Mexican Moz Fans Can't Be (Totally) Wrong" -- tapped by Matt Groening for Da Capo Best Music Writing 2003 -- Klosterman explores Morrissey's improbable new fanbase (and doesn't have to look far for material). There's a pre-Super Size Me/Fast Food Nation week spent eating nothing but McNuggets (and a follow-up interview with SSM director Morgan Spurlock), a lite metal cruise (Styx on a boat!), and visits to Akron-area psychics.

"Twenty feet away from me, Britney Spears is pantless," (duuuuude, trippy!) (it is!!) is how the Spears encounter begins. Later, the fact that Klosterman doesn't get to see her "secret garden" means, he declares, that "this is why I am a metaphor for America, and this is also why Britney Spears is a metaphor for the American Dream." Klosterman continues to (sorry) probe the angle, but mostly reacts like any reasonably sane person would when placed on a couch next to Britney Spears.

"'Why do you dress so provocatively?'" he asks. "She says she doesn't dress provocatively. 'But look what you're wearing right now,' I say, and I have a point, because I ask this while looking at three inches of her inner thigh, her entire abdomen, and enough cleavage to choke a musk ox. 'This is just a shirt and a skirt,' she responds. I ask her questions about her iconography, and she acts as though she has no idea what the word iconography even means."

"'That's just a weird question,'" she tells Klosterman when he asks her to "theorize about why American men are so fascinated with the concept of the wet-hot virgin." "I don't even want to think about that," she replies. "'That's strange, and I don't want to think about things like that. Why should I? I don't have to deal with those people... I'm not worried about some guy who's a perv and wants to meet a freaking virgin.'" The result is an odd, effective sketch of an abstract figure.

But, after all, isn't a journalist's job to point out things that are literally out of the ordinary? Isn't "news" just the plural of "new"? By so actively describing what is bizarre, Klosterman also strenuously implies that there is such a state as "normal" and that he is writing from some position nearby. We should trust him because, presumably, we are also normal, the so-called mainstream actually the paradigm for fucked-upness. Klosterman's best writing comes when he seeks to resolve the tension between these two places, and finds a third.

In "Mannequin Appropriation Project," a brief, brilliant piece originally published in The Believer (that should be filed in the "true" section), Klosterman literally refashions himself after walking into a Gap and buying a complete outfit from the most eye-catching mannequin. It is the application of creepy, fake normality (represented by the Gap) atop actual normality (himself).

"The first moment I looked into the bathroom mirror, I could tell it would be a controversial move. I looked totally fucking different in every fucking context. Who is this person? I thought to myself. I've never seen this person before. It suddenly dawned on me that I could disappear into the Witness Protection Program simply by combining a blue sweater with an untucked dress shirt."

"So we just went to lunch," he concludes, "and I spilled gravy on my Carolina sweater, because I am alive," he concludes, the two worlds resolved. True.

2.

Chuck Klosterman, however, is also capable of polarizing people simply for being himself. More accurately, he is capable of polarizing people because of who he is. His Esquire columns -- which comprise the bulk of "Things That Might Be True" -- often read like a blog, albeit one worth refreshing constantly. "I do not hate the Olympics," he claims in an entertaining piece of the same name, "I just do not like them at all." But, really: duck, barrel, meet Chuck. Crossing the line between "isn't that weird?" and "isn't that funny?" (and, to borrow Klosterman's clarification between hating and not liking the Olympics at all, there is a difference), other column topics include "Robots," "Pirates," and "Certain Rock Bands You Probably Like." It's nearly all hilarious.

If Klosterman sometimes gets carried away with straight-up hipster contrarianism -- the peacocking display of counter-intuitive aesthetics -- it is because he has become hipster contrarianism's voice in the mainstream. One of the few criticisms in Adams' Press slandering that had anything to do with Klosterman's writing was an accusation of favoring the "flip-flop chin-scratcher followed by a hokey moral." It's not just Klosterman, though. Tipping Point writer Malcolm Gladwell has made a career out of being counter-intuitive (albeit using a parade of scientists to support his conclusions, as opposed to theories about KISS). It is a product of the times, a way to (maybe) meaningfully rearrange bits of the data cloud in one's own image. As both Klosterman and Gladwell have discovered, being a well-read contrarian makes for memorable copy.

Even if not deployed directly, the flip-flopulation is the bedrock strategy beneath many of Klosterman's columns, as if he could pull the ripcord at any moment. In the insidery "Advancement," Klosterman gleefully explains the (seemingly) baked-ass theory that favors artists who "(a) do not do what is expected of them, but also (b) do not do the opposite of what is expected of them." The results somehow justify Lou Reed's brief, horrible attempt to rap in the late '80s. Elsewhere, Klosterman is subtler in his application, and the results often leave the reader with a sense of semi-conscious unease.

Klosterman sometimes reasons himself into corners. When he's ironically praising Reed, it's cute. Elsewhere, not so much. "You are being betrayed by a culture that has no relationship to who you are or how you live," he begins, abandoning the weird/normal game momentarily and assessing with such a surprising directness that something must be wrong.

"Here's the first step to happiness: don't get pissed off that people who aren't you happen to think Paris Hilton is interesting and deserves to be on TV every other day; the fame surrounding Paris Hilton is not a reflection on your life (unless you want it to be). Don't get pissed off because the Yeah Yeah Yeahs aren't on the radio enough; you can buy the goddamn record and play 'Maps' all goddamn day (if that's what you want)." All of which is well and true, but he soon extends it: "Don't get pissed off because people didn't vote the way you voted; you knew this was a democracy when you agreed to participate." Actually, Chuck, that seems like a fine reason to get pissed off.

There is no question that Chuck Klosterman is a dazzling writer, but his priorities sometimes seem misplaced -- or, at least, his skills underapplied. It is worth noting that in "You Tell Me," the fiction comprising CKIV's third section, Klosterman -- at the time, an Akron film critic -- is free of any of constraints and still chooses to write about the life of an Akron film critic. The story picks up a bit when a woman lands on the hood of the narrator's car, but it still comes off as a cool-but-kinda-unnecessary bonus DVD to a double-disc set of hits.

3.

Klosterman's most telling subject might be Billy Joel (also the topic of the fantastic "Every Dog Must Have His Every Day. Every Drunk Must Have His Drink" appreciation in 2003's Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs). After explaining to the New York Times Magazine's readers why Joel cannot possibly be considered cool, Klosterman has no choice but to argue his way home. In a bit of writing shared with the aforementioned companion essay, he uses a rhetorical switcheroo to get at the heart of Joel's songwriting (and the emotional raison d'être for all of Klosterman's hipster-trickster/weird/normal tactics):

"The irony, of course, is that Joel and Weber divorced five years after 'Just The Way You Are' won a Grammy for Song of the Year. Some would say this contradiction cheapens the song and makes it irrelevant. I'd argue that the opposite is true; the fact that Joel got divorced from the woman he wrote this song about makes it his single greatest achievement. It's the clearest example of why Joel's songs resonate with so many people: he expresses absolute conviction in moments of wholly misguided affection."

The same could be said for Klosterman. It is a great piece of writing. I still have little desire to listen to Billy Joel's music, but I have experienced it meaningfully through someone else who has, and that might count for more (in as much as reading about music can ever count for anything). When Klosterman expresses enthusiasm about contemporary music, he is enthusiastic about exactly what one would expect a 30something white male pop critic to be enthusiastic about: Wilco, Radiohead, The Streets, The White Stripes (all of whom are profiled generously and insightfully).

Not surprisingly, this is also where Klosterman demonstrates his crazy reverse skillz. Not that profiles are platforms for opinions, but Klosterman often expresses both sides. "Arrogance doesn't matter if you're right," he writes of Bono, though also calls him "hilarious" for sounding like Jesus, and wonders if he is "full of shit." If Klosterman's practiced cool sometimes freezes to apathy, so be it. He deserves a flip-flop and hokey moral of his own: Chuck Klosterman sounds passionless not because he is actually without passion, but because he possesses it in abundance. It is merely a coping mechanism.

Chuck Klosterman is not merely our man on the inside, he is one of us ("I am alive," he reminds). He wants to be able to both like U2 and find Bono absurd. While that might seem cheap, it's only because Klosterman knows he can have it both ways. Tastes aren't political beliefs.

It is not only okay to like Wilco and Ashlee Simpson (Susan Sontag made that safe), but it is also okay to like something and not like something simultaneously, to be both ironic and sincere. It is enjoyment at all intellectual costs. Klosterman isn't being contrary to insure your entertainment, he's doing it to insure his. His criticism works not to advise the reader if something is good or bad, but to provide a tactic: Sometimes stuff is weird. Sometimes it is normal. Often, it is both. Whoa, dude. That's, like, life.

4.

Then there's the whole "voice of a generation" branding, which surely pisses off Klosterman's detractors even more. Hell, the Associated Press recently ran a profile of him called, ahem, "Chuck Klosterman, voice of a generation." Come on, people. Get hold of yourselves. With apologies to Brittney, that's just weird.

Now, I love me some Chuck Klosterman -- and suspect anybody who makes it through an entire piece of his without giggling at least once is probably a fudge dragon -- but, quite frankly, I have higher hopes for my generation. Klosterman is great precisely because his scope is so modest. Even when he set out across the country to visit rock's most famous death sites in Killing Yourself to Live, his subject was still, despite the scenery, his own naval. And it was righteously entertaining.

As it goes, I'm perfectly happy to let Chuck Klosterman speak for me. He seems like a stand-up guy, with a solid head on his shoulders that recognizes strangeness for what it is. I happen to think that he really nailed what Brittney Spears means to American culture, for example, and feel well-represented when I see him expressing opinions in GQ or wherever. But I think that's mostly because I'm also a white, male, '70s-born music dork (which might be what made Klosterman available for "voice of a generation" status to begin with, or at least the white, male part).

If he hasn't already gotten sucked up into it, Klosterman clearly understands the zeitgeist. The question is what he will do with what he has absorbed. With his bread-and-butter senior writer gig at Spin terminated earlier this year, he has spent more time writing about sports for ESPN.com. Klosterman is a great writer, a creative writer, and -- who knows -- maybe he will end up being the voice of a generation. For now, he's got nothing but blank pages ahead.