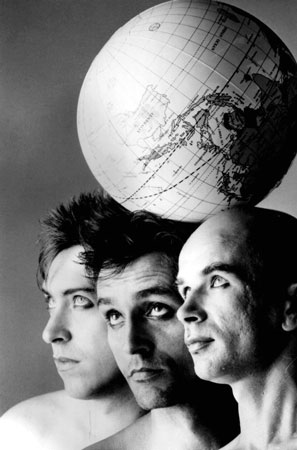

DISSIDENTEN

1989 promo photo by Ernst Wirz

Uve Mullrich/Karnataka College of Percussion/Turkish psych

Article/interview by Jay Dobis

(April 2022)

I spent the summer of 1973 in Israel studying Biblical Archaeology, working on a dig, and visiting many ancient sites, including on the West Bank. If you've ever had to read the bible -- a 2,000-year-old comic book forced upon way too many impressionable young people -- you probably picture its ancient cities as being large and impressive. In situ, they are tiny, maybe as big as a typical tennis court... At the end of the summer, my friend Izzy from the dig asked if I'd like to travel with him to Istanbul where his father had been born and raised before emigrating to Guatemala, and Izzy wanted to find out if all his father's stories were true.

Anyone who has flown into Atatürk Airport in the last 35 years, wouldn't recognize what we saw upon arrival in 1973: one runway. We had to wait on the plane until they wheeled out a set of steps. Then we waited on the tarmac until they unloaded the luggage. We picked up our bags and walked a short distance to the Arrival area, which amounted to a room about the size of a not very big elementary school classroom. Passport Control consisted of one guy and a bar of soap. Since three of us were American, we just showed our passports, and the guy used the soap to draw a line across our bags. Since Izzy was from Guatemala, he was escorted to a back room by a pair of "officers." After we waited impatiently for 15 minutes, he returned -- disheviled and visibly upset. We asked what had happened. Since he wasn't from a 'favored' country, they had slapped him around and demanded that he pay them money to allow him into the country. We were upset and shocked and asked: "How much did you have to pay them?" He said:"$1." "What?" "They demanded that I give them $1."

Istanbul was a very small city back then of 1.5 million people and not the sprawling metropolis it is today. In many ways, it was decidedly backward; a city that seemed neither East nor West; a city that seemed lost in time. The cars (and not very many of them) seemed 4 or 5 years out of date (and when I returned in '77, the cars seemed a bit newer, but still 4 or 5 years out of date). Istanbul in the '70s was the most fascinating, haunting, charming city I have ever seen. It was unique, but started to lose much of its charm with the massive influx of people from the Anatolian heartland in the 1980s. Then, it was a cultured, classy place. Today, it is a bloated shadow of its former glory.

[One day we walked through the Hilton Hotel (at the time, the only international hotel in the city) and heard some incredible music that sounded like some kind of strange Eastern cross between The Velvet Underground circa White Light/White Heat and The Doors. Twenty-five years later, I told Murat Ses (who had been the keyboard player for Moğollar in '73) about this. He said there was a very good chance that we had been listening to Moğollar. We wanted to enter the room where the band was playing, but we didn't have the nerve to crash a Turkish wedding party. In retrospect, we probably would've been welcomed.]

After four days in Istanbul, we were traveling on a ferry along the Turkish coast to Bursa. I was sitting on deck reading an issue of Melody Maker when a guy started talking excitedly to me in German. I didn't understand. He gestured for me to follow him: four sun-bleached platinum blond, blue-eyed men with their four sun-bleached platinum blonde, blue-eyed girlfriends who could only speak a little English. They were a Kraurock band from Germany that had travelled to Turkey to see the country and tape Turkish musicians. They were looking for influences. They told me the name of their band, and for the next 20+ years, I tried to find some mention of the band in New Musical Express, Melody Maker, Zigzag, etc. to no avail, and none of my many friends in the music biz around the world could help. I thought I would never find out anything about the band.

Sometime in '92 or '93, I was studying Indian music with Warren Senders (a master of khyal, a type of classical Hindustani vocal music) in Arlington, MA. During this time, Warren had been hired to try and turn a free local world music newsletter into a real magazine. He had to coerce me into writing for the magazine: "Jay, you know so much about music. You should share that knowledge with other people. Do you understand how refreshing it is to have a student who doesn't need to have the word 'MELISMA' explained to him." Very reluctantly, I agreed to write for the magazine (called at various times Rhythm Music Magazine, Rhythm Music Monthly, and Rhythm Music). I found I enjoyed it. In '94, I was asked to interview the leader (Uve Mullrich) of the band Dissidenten, which was set to tour the U.S. with the Karnataka College of Percussion. It was going to be the cover article, and my very first interview (and by phone). I was in an office in Cambridge, MA, while Uve was somewhere in Germany.

I had some prepared questions, and it went reasonably well, but the interview remained in rough shape because soon after, we found out that the lead singer of Karnakata was pregnant, so the tour was cancelled, and the interview remained unseen (until now). However, my favorite bits, which were off the cuff and never written up, are for me the most interesting.

I started telling Uve about the Krautrock band I had met on that ferry off the coast of Turkey in 1973. I told him that I'd been unsuccessfully searching for any info about the band ever since. He asked the name. I said: "Unterrock." He told me that two members of the band went on to join Missus Beastly (I use to have one very good album, Space Guerilla) and then the two moved on to join Embryo. Eventually, these two, along with Uve, would leave Embryo to form Dissidenten. I was a fan of Dissidenten and told Uve that I'd been a fan of Embryo since 1970.

Uve had been a member during one of Embryo's best periods, which was chronicled in a great documentary of their eight month trip from Germany to India by bus in 1979: VAGABUNDEN KARAWANE: A TRIP THROUGH IRAN, AFGHANISTAN, AND INDIA. The bus contained band members, girl friends, wives, roadies, and a documentary film crew. They drove thru Europe, the Middle East (including Turkey and Iran), Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the length of India, playing for and with the locals.

After Uve told me all about Ünterrock, I told him about the fantastic Turkish psychedelic music scene [Anadolu Rock] that had lasted from 1968 until Sept. 12, 1980 when a brutal military coup destroyed all popular culture in the country.

Uve was shocked. When he had traveled through Turkey in 1979, he thought the country was so primitive that he couldn't conceive of there being such a thing as Turkish rock bands -- let alone a flourishing, long-lasting psychedelic music scene (the first Turkish rock band was formed in 1957 by Erkin Koray).

I'm sitting in an office in Cambridge, MA about to interview Uve Mullrich. It's 1994. I've met and talked to many rock musicians, but it's the first time I've ever conducted an actual interview; and it's by phone, and I'm somewhat tense.

Uve still apreciates that '70s prog/psych sound.

Uve: It was an amazing time... Embryo. For three years just go on stage with virtually no rehearsal whatsoever -- the thing just happened on stage, and you'd have a couple of thousand people in front every night just following that stuff. It was a different universe to a certain extent... Maybe in India the conception of music is to find some of these elements found in the music of the 1970s. After years of all this compuerized stuff in music sometimes I think that there must be a revival of elements of a kind of hand-made music... In the fresh sense of of music growing on stage somehow, and people watching it. But I do not want to be nostalgic about it. I'm moving -- one is part of the times always. This is part of the reason that we formed Dissidenten: We felt that a big portion of this audience did not want to follow -- didn't want to open up, but the world carries on. Some people still walk around with the spirit of Elvis, with the clothes and the haircut and everything, which is okay, but it's not a way out. You have to carry on.

In Europe at the moment, the most amazing things are happening in Berlin because you have incredible groups coming over, and millions of people from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union are coming over who have never heard of Michael Jackson or Madonna. I think they will have an enormous influence: 400 million Europeans in the east -- they still have therir own music -- modern electric stuff with their own rules. I expect incredible musical things to happen there. Turkey is on he edge -- both Europe and Asia [I'd expressed my dismay at seeing Michael Jackson and Brooke Shield posters in Istanbul in 1988]. They have their own Madonnas... their own cult thing and industry. They are immune.

But for how much longer what with the proliferation of portable radios and boom boxes, etc?

Uve: Perhaps as Westerners we should not be so patronizing. For example, Louis Banks uses all digital, and western interviewers seem to have the attitude that he isn't entitled to use that stuff. Most of the musicians I meet are very open to new ideas and technology... You have MTV Asia now; they always have Asian groups topping the charts. It's part of the responsibility of people like you and me to facilitate mutual assimilation between cultures. Hopefully, there will be one world, but not one music, as various peoples utilize tech but retain their culture... India, more than the Middle East or Turkey, is a world unto itself. I asked how Dissidenten started.

Uve: In 1979 in the jazz festival in Calcutta, three members of Embryo decided to stay in India to make music and avoid the new wave thing that was going on in Europe, and I stayed in India for four years. We traveled from that festival in Calcutta to Bombay -- a very slow train that took three days or so. One night, we had to take a third class train -- horrible -- so we got off to to wait for for a train the next day at a little station. It was dark, no electricity, the few people that were there around a campfire (we didn't speak Hindi at the time) thought that the only place we could stay at this time was at the palace of this Maharajah. That's where we ended up. The Maharajah eventually became the godfather of my daughter, and we did a lot of things there: We lived with him and did a little film.Most of the little songs between tracks are done at his place. The CD is dedicated to River Namadan where the World Bank is building a huge dam, dislocating about 500,000 people and much [of the] rain forest. They are paying for a replacement program: The police round up people in a village and then truck them 300-400 KM into the desert and just dump them and say this is your new village here and give them no money or anything; it's horrible what is happening there.Thus, many people in India are opposed to the project. We [Dissindenten] were involved with artists in a little tour to protest the project... As Kurt Weill once said: "If you only understand about music, then you do not understand about music."Understanding the cultural context of the people is important.

I first went to India in 1973. I became friends with Trilok Gurtu, who is now becoming quite a well known Indian drummer, playing with Oregon and John McLaughlin. That was my first introduction to Indian music. I met his mother Shirpa Gurtu. They were singing, and I was trying to play the stuff on the guitar. I never had Indian classical music training. I prefer to get inspiration and do my own translation for myself.

Indian music is a different world. It touches certain 'spiritual' levels -- I hate that word because it has become so cheap. It forces you to look into yourself rather than practice the instrument to get into the music.

After playing with North African musicians for a number of years, why did you decide to move back to Indian music at that point?

Uve: Two years ago, we received a letter from this Maharaja that I was telling you about. In the letter, he said that they were planning to flood half of the place there and that Dissidenten had been pretty famous in India in the early 1980's, especially among young people in the universities and stuff. This woman in Bombay put together this tour, so we decided to go there. We had some business in India anyway. Various musicians in North Africa and India and so on frequently joined our little publishing, and we took care of their career in the West a little bit. We have a long connection with these people and our founding member and saxophonist Charlie Mariano [from Boston and has CD's out on ECM and Mesa with the Karnataka College of Percussion]. So we were there, and all these bits and pieces fell into place, and we thought 'why not put it together with the tchnical facilities we have nowadays.' So we recorded with them again, and now we are going to play with them live.

Tell me about Roman Bunka [from Embryo and who has played with Dissidenten].

Uve: Roman plays a lot with the Egyptian singer Mohammad Mounir, who covered our song "Telephone Arab." He asked us if he could do it. It was a minor success for him in Egypt. It fits into his whole style, his softer kind of sound. Since he is attempting a little bit of the electric thing, I thought he might take advantage and go a litlle bit wild with it, but it is nice. He is a very nice singer. In Egypt, the people go crazy when he is on stage... In India, Hindi film pop stars, more people listen to them than Michael Jackson or Madonna, just by virtue of the numbers. If something happened to one of them, girls would start jumping out the window. In Europe and America, no one is even aware that there are such enormous musical worlds next to them. While I believe that there are much more important things in the world than music, at the same time, music, or let's say art, is an abstraction of what is really happening in society; and with music, always a couple of years before. So I am pretty hopeful since we are all living on one planet. Everyone is conncected to each other. I hope that through the music, through understanding other places, people all over he world hopefully are getting a connection with one another somehow, a subconscious thing; that they're not only talking about money or arms or economic things but that it touches them on an emotional level, and they understand more about each other. Music is a helpful element -- you don't have to be educated. This is the amazing thing about going to Afghanisgtan. You play with musicians that cannot read or write; you can't speak each other's language, but you get together and you play, and immediately you touch a very deep human level with these people.

Why is your album called THE JUNGLE BOOK?

Uve: To make it appealling to the West. We didn't really mean to imply any colonial image. It's a work of literature that has entered the world. Coincidentally, the Walt Disney film was out again in Europe, which was quite helpful.

What is the blue figure on the cover?

Uve: I did that. On the one hand, it could be that old Mayan or Aztec symbol of fertility engraved in stone, which was found in stone about 50 years ago or so... Or it could be that I've taken a picture of a children's robot in a NYC toy store and put it through a Xerox machine a couple of times... We think it looks modern and ancient at the same time. It's our symbol.

Are there any ethnic musicians or groups that you really like that you think should be better known?

Uve: There's one group from Bombay with our old friend Louis Banks. Have you ever heard of him?

No.

Uve: He is the outstanding jazz player in India and also one of the biggest producers of Indian film music. He has this group called Sangam. I've worked with them as has Charlie Mariano and part of the Karnataka College of Percussion. It is an amazing fusion thing that is happening there, although they do not get to play play so much mainly because the college plays mostly with us in the West and Louis is doing his film work. He's actually from Nepal, but has been living in Bombay for 15-20 years. He's played with Maynard Ferguson and Charlie Mingus... a really amazing guy.

Okay Temiz is another. He first became known in the West for an album recorded with Don Cherry in the late '60's in Ankara. In the '70's, he moved to Sweden and was in great bands like Sevda and Oriental Wind. Okay has also played with Muhammad Mounir. He has a jazz band and a Turkish band with zurna [woodwind instrument] and Johnny Dyanni.