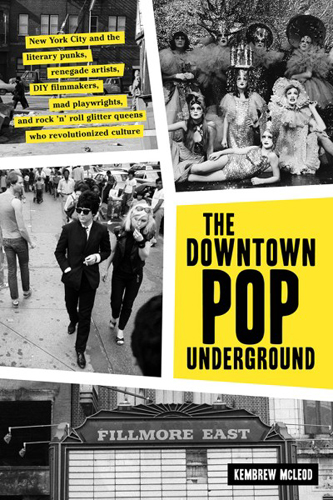

DOWNTOWN POP UNDERGROUND

Suburban Subversives

by Kembrew McLeod

(February 2019)

Patti Smith's audience grew throughout her CBGB residency with Television in early 1975, which created more momentum for the scene. "That was the first time when it started to get crowded," doorwoman Roberta Bayley said, "and I think by the end it was sold out." This was followed by CBGB's Festival of Unsigned Bands in the summer of 1975, which drew even more attention. "The Ramones started to get a following," she said, "and I think the Ramones were probably the first band to really build a fan base, and packed the place. Not long before it was just thirty, forty, maybe eighty people on a good night."

Roberta Bayley, who was there from the start, felt that the club was getting far too crowded for her tastes. "It just wasn't that interesting anymore," she said, "because all the people from the scene stopped going." Some grumbled that CBGB was ruined when all the kids from the suburbs began filling the club, which may be true, but that ignores the fact that several early punk artists came from outside the city. Smith and Harry hailed from New Jersey, and many others fled the New York suburbs for more exciting escapades downtown--like the Ramones. "My mother encouraged our creativity and expression, definitely," Mickey Leigh recalled. "I don't think there would've been a Joey Ramone if not for her urging us always to express ourselves artistically."

Charlotte Lesher, mother of Jeffrey and Mitchel Lee Hyman (the future Joey Ramone and Mickey Leigh), used to hang out in Greenwich Village and pursued her own creative path by making, among other things, quirky collages on metal lunch boxes. She eventually opened a gallery in Forest Hills, despite the lack of an art market in that Queens neighborhood. "But that's how we did things back then," Leigh said. "You just do it and then see what happens, and that's what my brother definitely did later on with his music." By the early 1970's, Joey began playing drums (using the name Jeffrey Starship) for the glam band Sniper, which performed at Mercer's and Max's Kansas City. Meanwhile, Leigh joined a short-lived band with two future Ramones--John Cummings and Tommy Erdelyi--which practiced in the basement of his mother's gallery, Art Garden. "We put the PA down there, so it had already been turned into a rehearsal place," he said. "And when my brother got into the Ramones, of course they were all allowed to rehearse there as well."

Erdelyi encouraged Cummings to start a band, and was more of a manager figure during the Ramones' early days. "Tommy's role became increasingly more important and pivotal in an organizational and artistic way," Leigh said. "Tommy really helped the whole thing gel and kind of helped it define itself." For Craig Leon, who produced the band's first album, the Ramones were like a performance art piece. "Tommy knew how to create this image of what they became," Leon said. "He originally studied to be a film guy, and he saw things in that visual sense. Even though the Ramones were definitely rock 'n' roll, they reminded me a lot of Warhol. The four of them had that deadpan Andy Warhol persona. They were, like, straight out of the New York art scene."

Joey Ramone started out as the band's drummer until it became clear that he was a much better frontman, so Tommy took over on the drum stool. Joey, Johnny, and Tommy expanded to a quartet when another neighbor, Douglas Colvin (later Dee Dee Ramone), joined on bass. Cockette Pam Tent and Dee Dee were already an item, which provided the band with a connection to the various downtown arts scenes. He got his cosmetology license and was working for the Pierre Michel Salon, but as Tent recalled, "Dee Dee wanted to be this nasty rocker around downtown. He and I had a lot of fun. Oh, my god, did we have fun. He was like a little boy and he would giggle at things. He would read comic books, but he used to drive me crazy. I came home from work once, and he let Johnny Thunders babysit my four-year-old son. He took him out on the town--Johnny Thunders, of all hare-brained people!"

The Fast's Paul Zone and Joey Ramone, courtesy Paul Zone

After the Cockettes' disastrous New York debut in 1971, Tent resettled in the city because she was already friends with David Johansen, who had just started out with the New York Dolls. "David was a good friend and he was around," Cockette Lendon Sadler said. "Pam had an East Coast connection to lots of people." She performed in The Palm Casino Revue at the Bouwerie Lane Theater with people from the Cockettes, Ridiculous, and Warhol crowds, and also was a member of Savage Voodoo Nuns. That drag group also included Fayette Hauser, John Flowers, and Tomata du Plenty--all from the Cockettes--as well as Arturo Vega, who later became the Ramones' longtime lighting designer and also created their iconic eagle logo.

Tent was staying with Hauser and Flowers in a loft at 6 East Second Street, right around the corner from CBGB, and Vega lived below them. "We introduced Dee Dee to Arturo," she said, "and after I left New York it became the Ramones hangout, that whole place." The Ramones' CBGB debut was on the same bill with Savage Voodoo Nuns and Blondie, a performance that was preserved by a videographer friend who was on the scene. Black Randy's footage captured wobbly versions of "Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue" and other primordial takes on songs that became punk standards. From the beginning, all the elements of the Ramones' aesthetic were in place.

"They knew exactly what they were going to do," recalled Kristian Hoffman, whose band the Mumps often played with the Ramones. "They already had ‘Beat on the Brat,' and a few key songs from the first album were already written." The Ramones' early sets were short, just like their songs, with each intro punctuated by Dee Dee's trademark "One-two-three-four!" count-off. "At first, the Ramones just had one long twenty-minute song, with different riffs running through," said Leon, who was tasked with transforming the group's live sets into an album. "They were all written as individual songs, but they never thought about it from a recording point of view--you know, ‘How is this song gonna end?' They'd just play and then ‘One-two-three-four,' they'd start the new one."

Most punk histories maintain that Sire Records paid a paltry $6,400 to record Ramones, but Leon said, "We never paid the full studio rate. It was actually cheaper than $6,000." The album cover had similarly modest origins. Sire hired a music biz pro to photograph the band, but they hated the results and instead chose an outtake from a more informal photo shoot with Punk magazine contributor Roberta Bayley. "We just went over to Arturo's loft and everybody was there," Bayley recalled. "We went outside, and first we found this playground, and then did a few different setups there against that brick wall."

The Ramones likely sold more T-shirts than records--especially in the 1970's, when mainstream listeners couldn't decode the catchy pop songs that lurked just below the surface guitar noise. When they opened for blues-boogie arena rocker Edgar Winter, the Ramones were met with a hail of bottles and boos. "There were people who wanted to burn the Ramones records and stuff like that because they were horrible, in their opinion," Leon said. "Ramones songs are now played at sports arenas and on commercials, so it's hard to understand how extreme they sounded at the time."

For every band like the Ramones, there were dozens of CBGB acts that didn't achieve wider acclaim, such as the Fast. Both bands shared a similar pop sensibility and emerged from unhip outer-borough neighborhoods (the Fast's bandmates grew up in Borough Park, Brooklyn, while the Ramones hailed from Forest Hills, Queens). Unlike the Ramones--pretend "bruddahs" who adopted the same surnames--the Fast actually were brothers: Paul, Mandy, and Miki Zone. Together, they became a ubiquitous presence on the downtown scene, spanning the glam, punk, and post-punk eras.

"We were a working-class family," Paul Zone said, "but I can't remember not having enough or not getting anything we wanted or needed. So my family could provide it if we needed an amplifier or a new guitar." The postwar economy of abundance fueled the growth of both the suburban middle class and underground culture. Bohemians benefited from the trickle-down of the economic boom, which allowed them to live on next to nothing; a part-time job or welfare benefits could subsidize a life in the arts. And out in the suburbs, the Zones' father could buy his kids musical instruments and other gear, even though he was a blue-collar sanitation worker.

Miki played guitar from an early age, middle brother Mandy sang, and Paul tagged along and followed his older siblings' lead. Miki obsessively bought rock magazines and gravitated to the photos of flamboyantly styled musicians, particularly late 1960s British bands like Faces and the Rolling Stones. "I always remember going to record stores with my brothers," Paul recalled, "and picking up the covers where the members looked somewhat different than everyone else." Not having the faintest clue about where to buy the platform shoes they saw in rock magazines, the Zone brothers assembled their own version with a hammer and nails. They sawed wood blocks and nailed them to the bottom of boots, which they painted silver and decorated with fake jewels; after their mother taught the boys how to sew, they began frequenting fabric stores as often as record shops.

Paul wasn't in his brothers' band at this point, but he was still heavily involved with the Fast. "Making costumes was just one of the many things that I had a part in," he said, "along with taking pictures and doing their lights and sound while they were performing, when I was about thirteen. By the time I hit high school, even in seventh and eighth grade, I was already wearing clothes that were just completely not accepted in a Brooklyn suburban neighborhood. I had platform shoes on. I was wearing satin pants."

What was it like growing up looking like that in Borough Park, a largely Italian and Hasidic Jewish working-class area of Brooklyn? "Of course, the people who would see us, slurs would come out of their mouths," Paul said. "They would obviously just think we were some sort of flamboyant homosexual, but that never even dawned on us. It was like, ‘This is what British rock and rollers dress like!' It wasn't working out, believe me. The band definitely never won the battle of the bands." But they tried. At one high school dance in 1970, the Fast played in front of a homemade backdrop of cut-out lollipops and stars, and other times they dressed a friend as Alice in Wonderland while other friends outfitted in nun costumes handed out cookies in the audience.

Even though the Zone brothers were oddballs, their family was still very supportive--especially their mother Vita Maria, who was the Fast's biggest fan. "We started growing our hair long," Paul said, "and that was a big thing back then, when a lot of kids could have been ousted from their family for that. But even aunts and uncles, they just never really thought of us as strange or outcasts." Still, they knew suburban life was not for them. "As long as I can remember," he added, "we wanted to get to that train as quick as we could to get to Manhattan. It was only a few stops away." When they started seeing ads in the Village Voice for an odd-looking band that turned out to be the New York Dolls, the brothers began frequenting the Mercer Arts Center, Club 82, and other venues.

Peter Crowley began booking bands at Max's Kansas City in 1974, and the Fast were among the first to regularly play there. "I met them hanging out at Max's, a little bit before CBGB's," recalled Chris Stein. "We met Jimmy Destri, our keyboard player, through them, and we did a lot of shows with the Fast at CBGB's." In 1976, Paul Zone debuted as the Fast's new frontman, and Debbie Harry introduced them at CBGB by waving a checkered racing flag. "We had a pretty good start because the name was established," he said, "so people knew who the Fast were." The future looked bright when they recorded a single with 1960's pop producer Richard Gottehrer, who helmed Blondie's first international hit singles, but the Fast were done in by a combination of bad management and bad luck.

(Even after Ric Ocasek tapped the Fast to open for the Cars on a 1979 stadium tour, commercial success eluded the brothers until Paul and Miki transformed into an electronic dance duo in the mid-1980's.)

The Mumps also had their fair share of misfortune. After An American Family became a hit in 1973, The Dick Cavett Show flew singer Lance Loud, keyboardist Kristian Hoffman, and the rest of the band out to New York to perform on the show. The two best friends had already made one attempt at living in the city and returned to Santa Barbara in defeat--"We had our New York experiment," Hoffman recalled, "and we didn't meet the Velvet Underground"--but this time, they stayed. After their television debut, various managers and record companies encouraged the band to change their name to Loud in order to cash in on their fleeting fame. "We hated that idea," Kristian recalled, "and Neil Bogart, who ran Casablanca Records, also wanted us to call the band ‘An American Family.'"

The buzz created by the series brought the Loud family to the attention of millions of people, including Lisa Jane Persky. The year it debuted, her father, Mort Persky, hired Pat Loud to write a piece about the show for Family Weekly, a newspaper insert that he edited. Lisa thought Lance's brother was cute, and a couple of months later, Mort introduced her to Grant Loud when he and the other Loud kids visited New York. She took them to see Holly Woodlawn perform at Reno Sweeney, an intimate cabaret located at 126 West 13th Street in Greenwich Village. "Because of Warhol films like Trash and Off-Off-Broadway," said Paul Serrato, who often accompanied Woodlawn as a pianist, "everybody wanted to see Holly perform at Reno Sweeney. It attracted everybody from the underground scene."

By this point, Lance Loud and Hoffman had fully immersed themselves in the downtown underground and become regulars at the New York Dolls' gigs at Mercer's. "We went there every single show," he said, "so we quickly met all these wonderful people like Paul Zone, who introduced us to everybody in the Lower East Side rock scene. Everyone happened to live in a one-mile-square neighborhood, and you would just see them every day. So we did everything together--the Mumps, the Fast, Blondie. All of these things intersected, and all of these crazy people hung out together."

Lance Loud was a magnetic frontman, though not necessarily the greatest singer (but this was punk rock, so it didn't really matter). "Lance loved performing, and he would sweat gallons," said Persky, who became a good friend. "He was just so blissed out when he was onstage." The Mumps played CBGB early on because Hoffman was working with Richard Hell at the vintage movie poster and bookstore Cinemabilia, which landed the band a slot opening for Television. Because of the hype surrounding An American Family, Loud was probably the best-known person in the nascent punk scene. "Lance was a larger-than-life figure," Blondie drummer Clem Burke recalled. "He was probably the first bona fide celebrity I ever met."

Pat Loud took a job in publishing in 1974 and followed her son out to New York, where she opened her small Upper West Side apartment to Lance and his friends. "She's the most marvelous mother," Hoffman said. "I mean, I really think of her as my other mother. She takes care of us all the time, to this day. So when she met Lance's colorful panoply of insane artsy friends, she would just invite them into her house for dinner without prejudice. They had a little kitchen about the size of a California closet, and she made all of this magic happen in that room."

Pat also used to drop by CBGB and other downtown venues to see her son's band play. "The Mumps were on the bill when she went to see Television," Roberta Bayley said, "when Richard Hell was in the band. I remember Richard dedicated a song to her from the stage, which was nice. I also remember Lance's mother invited Richard and I to an Oscar party at her apartment. I think she was just culturally open to different things and seeing what was going on, and really supportive of her son and his friends." Hoffman reminisced with Pat Loud decades later: "When I got sick, you just came down and put me in a cab and took me up to your place. I stayed at your place until I was well. It was good to have a Pat in your life." She nodded, "We had good times, Kristian. We had really good times."

Jackie Curtis, who was namechecked in Lou Reed's "Walk on the Wild Side," and Pat Loud eventually became very good friends; Pat even contributed to Curtis's drag wardrobe after taking revenge on her cheating husband. "One of his mistresses owned a clothing shop in Montecito," she said. "I went over to that clothing shop and I bought everything that fit me--which was a lot of stuff. I put it on a bill, and they let me walk out with all of these clothes." Having no desire to keep them, Pat donated the expensive fashions to the Off-Off-Broadway star ("I gave Jackie lots of stuff," she recalled).

Lance was also good friends with Hibiscus, who often came over to Pat's place for dinner. "That's why there's pictures of me there having dinner with Jackie Curtis," Hoffman said. "Holly Woodlawn was there. Hibiscus was there. You would think having all those crazy people there would be kind of like an art salon," Hoffman said, "but it was more like Pat cooking a delicious meal for love birds that had wet wings and they were lost. It was a place to go to get warm and have a good meal with someone who is completely accepting and loving."

Back when Loud and Hoffman played in a high school band with drummer Jay Dee Daugherty, Pat kept them supplied with treats and refreshments during rehearsals. "Jay and I went through lots of similar experiences together," Hoffman said, "and I looked upon him as one of my closest friends. And when he quit the Mumps to step up into the world of Patti Smith, her future wasn't ensured. This is before Horses, and she had only done the ‘Piss Factory' single. I thought, ‘This person who I had all of these adventures with, I played on Dick Cavett with, we moved to New York together--we've been through all this stuff--then the minute he gets a better opportunity, he just leaves?"

Daugherty's departure devastated the Mumps, and as a favor Clem Burke filled in on drums and juggled two bands for a while. "My plans were contingent upon the Blondie situation," he said, "as far as working with the Mumps and Lance." Burke stopped playing with them when Blondie's first single was released, so the Mumps cycled through several ill-fitting drummers while playing CBGB and other places. "We probably would have had a record contract if it hadn't been for that," Hoffman said, "because we would have been right there at the peak of the scene exploding. Instead, we were playing with these lousy drummers, though we still had a lot of fun."

"For me it was just sort of obvious who was going to get signed, who wasn't," Persky said of the feeding frenzy that began after Patti Smith, the Ramones, and Blondie inked record deals. "I think Lance was threatening with his sexuality in a way that Debbie Harry wasn't, and I don't think any record company was ready to bankroll a band with a gay singer." The Mumps keyboardist agreed: "The fact that Lance was gay didn't exactly help. Really, how many openly gay men were in a rock band then?" Hoffman went on to play with several other prominent downtown figures--Lydia Lunch, James Chance, Ann Magnuson, Klaus Nomi--but wider recognition eluded the Mumps. "It kind of hurt to see all your friends that you played with over and over and over again going off on this adventure. But I also was very proud of them."