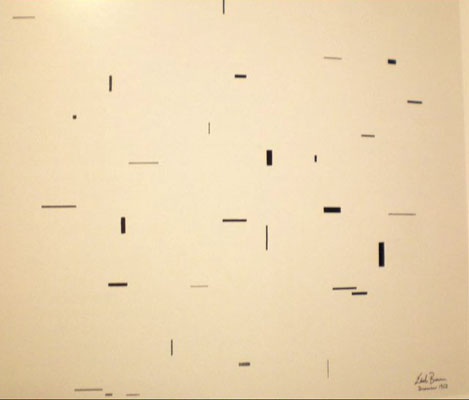

EARLE BROWN

The Poltergeist in the Machine

by Daniel Barbiero

(December 2022)

It might seem curious that Earle Brown, a composer best known for open-form, essentially improvisational graphic works like the classic "December 1952," would have been concerned with serial music. But in 1965, Brown addressed topics in that paradigmatically closed-form style of music when he published an article titled "Serial Music Today."

As its title indicates, the context for Brown's article was the state of serial composition in 1965. And perhaps not surprisingly, given Brown's background and interests, the article considered how serial composition's methods related to some of the other ways of organizing music that a number of contemporary composers, in both Europe and America, had been experimenting with. These other ways included the kind of indeterminate or "aleatory" writing that left many of the details of a composition either open to the performer's discretion or determined by chance operations deliberately working beyond the reach of the composer's personal preferences and intentions. Brown wrote from the point of view of someone who by the early 1950's had already composed classic indeterminate graphic scores, and who had had a background in jazz improvisation besides. It would seem natural then that he would consider the situation of serial composition in relation to developments in the open-form, experimental compositional style with which he was intimately familiar.

Something Will Always Escape

Brown's argument, in brief, was that contemporary serial composition had in fact begun to take account not only of chance and indeterminate compositional methods, but of the larger problem of what he called "freedom and iconoclasm" as well. For Brown to find, as he did, room for a degree of indeterminacy and freedom within serialism's purportedly systemic, total organization of musical material--pitch, rhythm, dynamics and articulation--might seem somewhat quixotic. But he looked not at the so-called precompositional structures of serial music--that is, the formulae constructed in advance of the composition itself, which would determine how the various musical parameters would be systematized and the compositional details generated--but rather at what he called the element of "response." As he wrote,

Everything can be serialized except... the response of [the composer] to the series, the musician to the notation, the listener to the results of all of these, and [the composer's] own response to the inevitable difference between what one wants and what one gets.Brown was writing at a time when serial composition was still, in terms of prestige and influence, a strong force in American art music. Although his immediate focus on serialism is no longer a timely subject--serial composition by the mid-1970s had lost the primacy it had, or was felt to have, within American art music--the more general problem his article raised is still of interest and indeed, would appear to be inherent in any kind of music that relies on interpretation and performance for its realization.

I want to focus here on the second of the factors Brown referred to--the response of the musician to the notation, but in its broadest sense. That is to say, the response of the performer to the score, using "score" as a kind of shorthand for all that it might imply: the marks on the page not only as a "text" to be read properly, but as the material trace of the composer's intention and the composition's integrity--structural, conceptual, affective, and what-not. Thus, the general lesson I want to take away from Brown's piece, and its deepest point of insight, is that the performance of even the most systematized and fully determinate score involves an irreducible element of discretion that he correctly identifies as consisting in a "contextual freedom of action." Seen from the perspective of the performer as interpreter and executor, this freedom of action entails an element of subjectivity, and hence unpredictability, into any musical performance in which a score must be realized by a performer. It is a variable that resists serialization or any other form of codification; it is a variable that embodies freedom. But in its unpredictability it is a freedom that can be a mischievous force of its own, something lurking in the shadows of the performance--a freedom that haunts as well as animates the realization of the composition. Not exactly a ghost in the machine of the composition, but rather more like a poltergeist.

What Brown's article suggests is that there is what we might call an indeterminacy at the heart of musical realization, and the virtue of his piece was to choose what in many respects is the most difficult, and even unlikely, example for making that case--the example of a kind of composed music in which the values for all parameters are systemically determined. But the integral serialism Brown had in mind is hardly the only kind of composed music in which all musical variables are given fixed values; in principle, any composition can notate and fix every aspect of the music that can be notated and fixed. And yet, as Brown intuited, something will always escape. This is for the simple reason that any score, no matter how minutely specified its parameters and no matter how detailed its notated directions, must be realized, which means that it must be interpreted--translated into a performer's framework of understanding--and executed. It is in this context of concrete interpretation and execution that freedom of action comes into play. Performance turns out to be a matter of hermeneutics, which provides an opening to freedom.

Performance as Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics, as meant here, is simply the art and practice of interpretation. Hermeneutics originally referred to a process of textual interpretation, but over time it has been understood to apply to other fields and to the human lifeworld more generally. The hermeneutics of performance draws from both the original and the more generalized conceptions of hermeneutics; it begins with the interpretation of a text--the composition's score--and culminates in the practical interpretive stance embodied in the performer's actions in realization of the score. As such, it is an inescapable element in the performer's response to the composition he or she is to perform. To approach performance from the hermeneutic stance is to recognize the composition as a locus of a given meaning that must be understood, assimilated by the performer/interpreter, and then realized in the gestures and sounds that themselves represent the interpretive enactment of that understanding and assimilation. If the performance is the context in which contextual freedom of action arises, interpretation is the context in which performance is made possible--it is the deep structure underlying and affording the freedom of action the performance puts into motion.

Interpretation at a first pass would seem to be simple enough--just a matter of making sense of, or finding the meaning of, the notes on the page. But before this can happen a prior step--call it a pre-interpretive interpretation--has to be taken, sometimes consciously and sometimes not. This prior, pre-interpretive step consists in what Patrick Colm Hogan, in On Interpretation: Meaning and Inference in Law, Psychoanalysis and Literature, has termed a stipulation. Before interpreting a score (or for that matter, any other object requiring interpretation), we must first stipulate what criterion or criteria, in the form of a type of meaning, will serve as the interpretive point of reference. What kind of meaning, in other words, is interpretation meant to address and to use as its framework or guide? In the case of a musical score, the two major possibilities for meaning-criteria would be, 1) the composer's intention, or 2) the structural logic of the piece. Do we as interpreters try to bring out what the composer intended vis-a-vis how the piece sounds, how it develops, its mood, tempo, and so forth? Or do we choose to be guided by a view of the score as a more-or-less independent object characterized by a particular set of elements whose meanings are governed by their internal relationships? Once one of these two criteria has been chosen, the interpreter can go on to make the particular choices or moves that will align with whichever type of meaning has been chosen, and which ultimately will guide the performer's translation of the score into his or her own language of musical gestures--call it an idiolect--in terms of which the interpreted score will be executed.

Execution involves a kind of translation as well, but of a different kind. It involves the performer's framework of competence or technical skill, but is affected by additional factors as well--attentiveness, mood, response to the situation in which the performance takes place, and so forth. Execution, in other words, involves not only technical factors particular to the performer, but situational or contextual factors--such as, for example, the acoustics of the room, the perceived state of the audience, and the awareness of one's own performance as it unfolds, an awareness that feeds back into and subtly or not so subtly shapes the performance-in-progress. All of these factors are the objects of the performer's interpretive judgment (albeit generally tacitly) and any or all of which may have an impact on how the sounds are actually produced. Execution, in other words, is more than the setting into motion of certain physical movements correlated to aspects of the score; there is an ongoing interpretive element here as well, although one not directly tied into the score and, as noted, one most likely taking place beneath the threshold of conscious awareness.

In the final calculation, the hermeneutic activity involved in translating the score into sounds is a three-and-a-half stage function, as the score is as it were filtered through the performer's interpretive judgment (which, as we have seen, includes the preparatory half-step of a pre-interpretive judgment), technical capacities, and response to the performance situation. At each of these stages, the performer's freedom comes into play, albeit in different forms and to different degrees, but what they all share is a fundamentally interpretive nature.

The performance of any type of score involves the kind of interpretive activity described above. This is true of conventional scores as well as the serial scores Brown was concerned with in 1965. But it may be the open-form score, of which Brown's own "December 1952" is a classic example, that provides the context par excellence for creating the conditions in which the hermeneutic of performance can take place, and hence for affording the performer the freedom of action Brown discussed in his article. Open-form scores--scores using graphic or other suggestive or approximative notation, scores inviting performer choice in selecting and arranging which parts to play and when, scores involving opportunities for improvisation of whatever sort--trade in making explicit, that is, bringing to the forefront, the hermeneutic process more-or-less implicit in more conventional scores. Open-form scores in fact push the performer's hermeneutic activity to the point of crisis, in the original sense of making it the site of judgment.

Freedom and Failure

One surprising way in which this free subjectivity can make itself known is in the unlikely guise of error. In fact, the radical point implicit in Brown's piece--if we may be allowed license to push it this far, and in this direction--is that the possibility of the realization of the performance is always predicated on the possibility of failure. What makes possibility possible and not inevitability is the possibility of a mismatch between what is desired or required, and what actually is brought about. The possibility of failure just is the mischievous face of freedom, the face whose expression is unpredictable. The freedom inherent in interpretation may manifest itself as misinterpretation, which introduces open joints or points of slippage between the composition and its realization. Call it an occupational hazard, something just built into the "contextual freedom of action." Error, which always exists as a possibility when freedom of action or interpretation comes into play, lies dormant at the heart of any realization of a composition, no matter how determinate the score.

But here I should make it clear that not all failures are indicative of freedom. The errors of the unskilled instrumentalist playing out of tune, or the poor reader playing the wrong notes or rhythms, don't manifest freedom so much as the unfreedoms of limited competence. Thus, for the sake of argument, I want to assume a technically competent performer and focus on the interpretive, rather than the mechanical, side of score realization. For it is precisely in his or her capacity as an interpreter that the performer's freedom is disclosed through the possibility of error. Brown's "contextual freedom of action" implies the freedom to get it wrong.

Consider a composition that meticulously sets out the values for all of the parameters it contains--pitch, duration, dynamics, rhythm, articulation, and so forth. The fact remains that, no matter how detailed the score's specifications are, it still must be read, comprehended and assimilated, and ultimately translated into concrete gestures. Every one of these points--reading, comprehension, assimilation and translation--represents a moment along what Brown aptly termed an "ambiguous continuum" of cause and effect. It is in addition a complex continuum in that each cause is itself the effect of multiple factors, the markings on the page being only one. Other factors that come into play are the performer's own judgments, skills, limitations, habits, practices and so on, each of them in turn the product of a particular history on the basis of which any future performance will by necessity arise. At each point along this complex, multidimensional continuum a choice must be made, which is to say that each point represents a moment in a human, interpretive response, which inevitably brings into play any given number of uncertainties, idiosyncrasies, flashes of brilliance, indifference, and incomprehension, and finally, the possibility of failure. Failure may occur at any point along this continuum--as a failure of interpretation, or of execution.

Failure of execution is perhaps the least richly suggestive of the two major areas in which failure may occur. Purely mechanical failures and slip-ups may be interesting for what they may reveal of the performer's gestural habits and technical limitations, but in the end, they would seem to be less interesting than errors of a more discretionary kind of interpretation. These latter are (seemingly) more subtle and telling of the performer's engagement with the work. But consider the possibility that some failures of performance may fall in between purely mechanical errors and fully interpretive judgments. Say, for example, a performer substitutes a tone sequence for the prescribed tone sequence in a serial work. Is this is a mechanical errors that can be ascribed to habits of muscle memory? An implicit interpretive judgment in which the performer overrides the score on the basis of a tacit sense or "feeling" that the substituted sequence is what really sounds right in context, never mind what the composer intended? Is it, in other words, a simple mistake or a revelation of sensibility? (Does muscle memory, as ingrained habit, represent a kind of fossilized trace of sensibility--an interpretive turn turned to sediment?) And could something like this have happened during, say, the first and not entirely accurate performance of Milton Babbitt's "All Set" by a jazz ensemble unused to performing serial, and perhaps even entirely written, compositions? Were the mistakes in that performance better thought of as improvisations--as, to paraphrase Brown, the performers' responses to the series--rather than as simple mistakes?

Open-Form Scores and Failure

However we attribute its cause, some slippage between composition and performer--some degree of "failure," if we choose to call it that--is always present as a possibility when there is a question of interpreting a score and translating the composer's intentions into the performer's language. No score holds no room for error--no score can circumvent the free possibility that the performer will fail in some way to realize the intention it embodies. This is fairly obviously the case for fully notated scores of some complexity, but it holds for other types of scores as well. Most interesting in this regard may be open-form scores, which by definition build in a great degree of freedom for the performer. They leave much room for interpretive freedom, but in doing so, do they leave enough room for failure?

The answer would have to be "yes." Even the most open of open-form scores places constraints on its interpreters, who can fail to recognize or, in the--one hopes--rare case of a bad faith performance, fail to accept its constraints. In a sense, indeterminate or open-form scores seem to court error. They not only make error possible, simply by the fact of their being scores and thus requiring interpretation, with all of its built-in fallibility; by their very lack of determination in specifying values for musical elements, they virtually invite error as a kind of creative strategy. The performer has to approximate what it is the score calls for and in doing so, may err by, for example, overshooting or undershooting the desired mark. Say the score uses an unlined staff populated by markings symbolizing pitches. By its very nature of setting out pitches in a relative rather than absolute manner, it can only leave one to guess at the pitches' values relative to each other by approximating the size of the intervals involved. The eye has to measure relative height or distance for the phrase to take concrete shape as specific pitches and durations. Of course, the eye is fallible and by no means beyond outright mistakes--skipping over a mark, moving up rather than down as indicated or vice versa, misreading two marks at an equal height as staggered, and so forth--besides which, there is always the likelihood of inconsistencies creeping in. One might play the same set of marks different ways each time rather than the same way at different times.

The error--if it is an error--involved in playing the score's marks inconsistently quite naturally raises questions. Is it a case of violating the composer's intention, as the latter has left its trace on the page? Or is it a violation of the piece's structural logic, which may reasonably be assumed would require something like consistency in the interpretation of given marks? Or, given the indeterminate score's openness, can we even determine which measure of meaning has been violated? A good faith effort to honor the composer's intention may result in looking for clues to that intention in the score's structure, which may only provide vague hints. On the other hand, interpreting by the lights of the score's structural logic may require the performer to resort to questioning the composer as to what range of values are permissible or desirable for any given mark on the page. This latter tactic is not at all unusual, and may in fact represent the norm rather than the exception. Perhaps for open-form or indeterminate scores, the pre-interpretive move of stipulation may itself be indeterminate. It may simply end in an interpretive impasse, or aporia.

Of course it may be the case that the score permits and even encourages creative inconsistency in its realization; it may be that for the composer of a given open-form composition, there are no mistakes, assuming a good-faith effort at realization. But even in those cases, it may be that the sounds don't really correspond in some discernible way to what's notated on the page, whether or not the discrepancies are welcome. For example, graphic scores using relative pitch notation may set out phrase shapes that the performer is intended to follow. The marks on the page, as inexact as they are, still constitute criteria against which to judge the sounds made to realize them. A certain amount of leeway in interpretation is to be expected, but beyond a certain point, it is possible to speak of an error or of playing something that goes against the composer's intentions or alternately, falls outside of the structural logic of the piece.

(Or could we instead say that the failure lies not with the performer but with the composer, for not having chosen a system of notation exact enough to convey his or her specific intentions? Would this failure represent a failure imposed by the built-in constraints resulting from the pre-compositional choice of a notation system, and thus, in effect, represent a foregoing of the composer's freedom to respond to that system? More generally, does commitment to a given type of notation, conventional or otherwise, while opening up possibilities for the realization of the composer's contextual freedom of action, also bring with it the free possibility of failure in the form of the composer's not being able to convey an intention in an effective way?)

Summoning the Poltergeist

There are limits to interpretation then. But we can, in principle, imagine a scenario in which the composition--presumably gently, and in a friendly manner--pushes the performer beyond those limits, to the point of producing a failure. If failure is an index of freedom, a composer interested in having the performer reveal him- or herself in his or her freedom may attempt to create a situation in which performer failure has a good chance of happening. The solicitation of error, in other words, may suggest itself as a legitimate, if unusual, compositional strategy--a way of summoning the poltergeist to make its presence known. At one extreme is a case like Tom Johnson's "Failing," which was written if not to trip up the performer, then at least to make failure a very real possibility. More generally, we can imagine composing in such a way that errors of interpretation will be likely to make their way into a performance. Why would anyone want to do that? Surely not to embarrass the performer--good faith works both ways--or to set the work into an oppositional relationship to the performer, except perhaps between consenting adults. Rather, soliciting error would be a deliberate compositional tactic meant to let the performer reveal his or her unique sensibility through the kinds of errors he or she makes. Think of certain kinds of errors in musical interpretation or performance as something like the musical equivalent of Freudian slips, revealing something true of one, albeit inadvertently. What would be revealed by a deliberately encouraged musical error? Ideally, the sensibility of the artist committing the error. In effect, error would be solicited in order to allow the performer to substitute his or her own sensibility for the sensibility of the composer. There may be a sense in which error is no error, and no approximation is wrong, if the idea is to create a situation in which, through a good faith effort to realize the score as written, one gets it (ostensibly) wrong and plays instead what seems right by one's own musical lights. Deliberately creating a situation in which this is likely to happen may be a strange way to go about revealing the performer's freedom of action, but stranger things have been done.

In the end, the performer's interpretive judgment, with all of its attendant hazards, is an irreducible manifestation of the freedom that pervades every performance, even if the composition is exhaustively notated. There is always the possibility, whether through error or good-faith misinterpretation, of a slippage between what the composer intended or expected to hear, and what the performer actually delivers. It doesn't even have to be a question of error or misinterpretation either. It could just be the natural outcome when the product of one sensibility--the composer's--is interpreted and realized by the performer's necessarily different sensibility. (One could even say, with a minimum of exaggeration, that every interpretation is a misinterpretation, and every reading a misreading.) Whatever the cause, Brown's "inevitable difference between what one wants and what one gets" will always be, well, inevitable. Varèse was surely right to assert that the contemporary composer refused to die, and by the same token, Brown was right to remind us that the freedom of action implicit in any musical performance just as stubbornly won't disappear.