Elvis for Everyone!

Presley's 1965 Hall of Mirrors

By Kurt Wildermuth

(February 2022)

Hmm... Elvis for Everyone! You may be thinking: Everyone? Who would this everyone be? Also--given that we can no longer assume shared cultural knowledge--in your silo, your splendid isolation, you may be thinking: Who is this Elvis?

We'll get to everyone, but first let's identify Elvis through an origin story. Smack dab in the middle of the twentieth century, a flaming star appeared, as though a sun had burst. This ball of fire changed the world, musically and culturally. Its full name was Elvis Aaron Presley, but in no time at all it was known universally as Elvis.

Like the Nexus 6 replicants in the 1982 movie Blade Runner, Elvis burned brightly and briefly. From 1955 until about 1958, Elvis ruled as the king, the replicant Roy Batty, of rock and roll. There had been huge stars before him, such as Frank Sinatra, but there had never been a rock and roll star of this magnitude, and the world reverberated from the energy given off by the new phenomenon.

Then a stint as an inductee in the U.S. Army, from 1958 to 1960, robbed Roy--sorry, Elvis--of momentum. A series of Hollywood movies, from 1956 to 1969, and recordings of material whose quality ranged from top shelf to somewhere near the bottom of the barrel left the king's crown severely tarnished.

In 1968, Elvis starred in a TV special clad in black leather, looking happy, healthy, and focused as he rocked like it was 1955 again. After his so-called '68 comeback, he issued well-regarded recordings, including some of the hits he's best known for. But years of unevenness, decline, substance abuse, and performing in white jumpsuits followed.

Elvis was meant to burn brightly and briefly. When some cosmic force needed a torch to fire up the world, the torch was supposed to get consumed by the pyre. Yes, Elvis started the fire. However, he escaped the conflagration and lived past his appointed time, dying in 1977, at age 42. All the while, through the 1960s and '70s, the flames of the '50s raced around the world, whose appearance changed in ways that probably bewildered the igniter.

From country boy to truck driver to pioneering rock and roller to hugely famous and wealthy entertainer to bloated self-parody, Elvis journeyed but sometimes seemed like a bystander. He blazed a trail that continues to set a standard for stardom but also serves as a cautionary tale.

Here at the start of the twenty-first century, we're accustomed to stars being savvy--like, say, Madonna or Beyoncé, each of whose business sense has been celebrated as much as their performing talent. We expect stars to chart their own courses, to know themselves and how to deliver their uniqueness for our consumption. Elvis wasn't like that. Whether Elvis had a choice or not, businesspeople picked most of the paths on his journey. In looking back at his career, Elvis partisans thrill at the occasional sense that he actually chose this move or that, was actively involved in making the cultural products that bore his name.

In 2021, when introducing Elvis's 1962 movie Follow That Dream on the Turner Classic Movies TV channel, host Ben Mankiewicz noted that there isn't a rock star today who hasn't taken something from Elvis. But which something and from which Elvis depends on which rock star. Metallica's James Hetfield took Elvis's physical stance and complicated machismo. Miley Cyrus took his growl--and took his scandalous pelvic gyrations into twisting new forms. Billie Eilish took his pout. Elvis Costello took his first name. Michael Jackson took his title, "king," but applied it to pop. Kanye West took his eccentricity. Lots of people try to take his versatility; Prince succeeded, exceeded, receded--then, like Elvis, died alone. The late Kurt Cobain might have taken the message that being an entertainer can be worse than being dead. But no career-minded artist would take his quality control, whose faultiness helped yield a complicated legacy.

As did his being considered the king: "Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant shit to me," Public Enemy rapped in 1989. So much for "everyone." In the context of Black Lives Matter and our push-me-pull-you reckoning with systemic racism, it's easy to see where PE was coming from. Because Elvis loved R&B, he appropriated Black vocal stylings. Because he also loved country music and gospel and pop, he brought those styles together with R&B and thus became the face, if not the inventor, or more accurately the catalyst (the catalytic converter?), of rock and roll. The figures he drew inspiration from came to seem, at least for a time, like footnotes to his achievement.

The entrepreneur Sam Phillips recorded Elvis's world-changing first tracks after the truck-driving hillbilly cat, at age 18, stepped into Phillips's Sun Records, in Memphis, to record two songs for a fee. "I don't sound like nobody," Elvis told Phillips's secretary. Phillips already knew that if he could find a white man who sang like a Black man he could sell records to people who wouldn't touch "race" music. Phillips's knowingness taints Elvis's legacy, whether or not either man was "racist."

Whatever the baggage attached to Elvis's Sun recordings, the most raucous or haunting of them feel as vital as ever. Elvis was working out the finer and the unrefined points of rocking out, rockabillying, and crooning with his "band": guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black. And the power in those recordings carries into the best material the Sun king recorded after he--with Moore, Black, and drummer D. J. Fontana in tow--first moved to RCA Records.

Elvis's eighth album for RCA, 1965's Elvis for Everyone! , displays some of the king's early power, but it shows off other aspects of the man as well. From afar it seems like an odd creation and a curious choice for analysis. Yet this collection has hidden depths. It strongly hearkens back to the Sun sessions, gives us glimpses of the performer Elvis had become ten years after those sessions, and encapsulates his transformation from rocker to entertainer. It's a series of opportunities for contemplation, even celebration, of the star and his business and the way they worked in the mid-1960s.

All of this significance happens within 24 minutes, the album's running time. A total of 12 tracks range in length from 1:21 to 2:42. Even in 1965, that was short for a long player (LP). Why didn't Elvis put more music on this record? Elvis might not have had much to do with the record.

We have come to expect albums as statements of purpose, but Elvis for Everyone! wasn't the product of artistic vision. It was product, assembled by RCA to ship units. Earlier that year, the company had released Elvis's soundtrack for his movie Girl Happy. Later that year would come his soundtrack for Harum Scarum. Meanwhile, what better time to bring together tracks Elvis had recorded not just in different sessions but in different years, periods, contexts? Unify the sound to some extent and you have a gift not just for fans but for everyone!

In those seemingly innocent but certainly pre-Internet days, everyone would have received the product and its promotion without the ability or inclination to dig beneath the surface, an ability or inclination we now tend to take for granted. When in 1964 those Elvis acolytes the Beatles titled their fourth album Beatles for Sale, they were being wry, even cynical. After three years as professional recording artists, they were worn out and generating material, not always their best, under duress or at least by contractual obligation. When RCA chose the title Elvis for Everyone! , it was more straightforwardly reflecting the commerciality of a hodgepodge. Everyone gets a little Elvis, the Elvis of their choice.

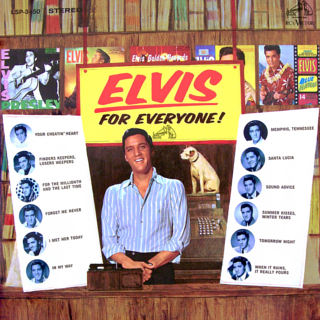

The album cover even celebrates the sales push with a pointedly artificial collage: a photographed Elvis represents a salesclerk at the counter of an illustrated record store. To his right and left, posters advertise the song titles, each one accompanied by a different photo of Elvis. In front of him sits a record player. Behind him sits an old-fashioned cash register, atop which sits the RCA mascot dog, traditionally listening to "his master's voice" but seemingly on loan to Elvis for promotional purposes. Over the top hang enlarged versions of some of Elvis's previous album covers.

The in-your-face marketing on this jacket could have been offensively cheesy, as so many slapdash Elvis album covers are. In terms of design, his sprawling catalog presents countless examples of what not to do. This cover, however, is fun to look at, funny, and appealingly retro. In addition, the title and cover art are so wedded to the nature of the product that, if you didn't know better, you might think the artist had intended this creation as a concept album: Elvis Not Just for Sale... Elvis Sells Out!

Similarly, if you didn't know otherwise, you might think the album's opening song, "Your Cheatin' Heart," originated with Elvis. Or you might think it's by someone other than Elvis, because he doesn't sound like himself. To his credit, he also doesn't try to sound like the song's composer, Hank Williams. Hank had played honky tonks, knew the details of a honky-tonk life, and sang the praises of going honky tonkin' ". . . baby, all night long." Here--but actually in 1958, when it was recorded--Elvis and an augmented Sun sessions band sound like they're playing in a honky tonk. There's no pedal steel on this track, so it doesn't have any country whine, yet it's more straightforwardly country than the music Elvis made at Sun. It also rocks in spirit, more so than a lot of so-called rock.

Elvis remains comfortably in his middle range here, but he employs something theatrical, a hollowness that uncharacteristically indicates a put-on. (Four years later, Bob Dylan would do something similar with his voice on his full-fledged country album, Nashville Skyline. That approach may be one of the many things Dylan took from Elvis. From Dylan, Elvis took the opportunity to cover, in 1966 and breathtakingly, "Tomorrow Is a Long Time," which Dylan once called his all-time favorite version of one of his songs.) On "Your Cheatin' Heart," the unusualness of Elvis's vocal, like the handclaps that appear briefly toward the end, add to the appeal of his paying tribute to Hank--one American legend untraditionally honoring another.

This very strong opener is followed by a stunner of another kind: "Summer Kisses, Winter Tears" finds Elvis emoting in some exotic locale. This song was one of many written especially for the king by Ben Weisman and Fred Wise, here collaborating with Jack Lloyd. Recorded for Elvis's 1960 movie Flaming Star, this track originally appeared on a 1961 extended play (EP, meaning a 7" record with two songs on each side). The title track was "Surrender," a slightly melodramatic seduction song. On "Summer Kisses," the romance is gone but not forgotten:

The fire of love, the fire of love

Can burn from afar

And nothing can light the dark of the night

Like a falling star

Elvis luxuriates in the language, which for an early '60s pop song is downright Shakespearean. He also seems inspired by the shimmering music, as an Eastern-sounding guitar figure, a loping rhythm, jazzy piano, and background vocals like thick curtains place him somewhere beautiful but claustrophobic. The air is fragrant but perhaps running out. Elvis inhabits this scenario without really getting into character. As a singer he often does that--adapting his style to the occasion but staying respectfully on the surface of the song.

As a testament to the frisson of eerieness on this track, David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti crafted a version for Julee Cruise to deliver in her spacey pop style. Their collaboration, on the Until the End of the World movie soundtrack (1991), makes a nice icy counterpoint to Elvis's warmth.

Track 3 of Elvis for Everyone! is "Finders Keepers, Losers Weepers," cowritten by Dory Jones and Ollie Jones. In 1991 it was included on The Lost Album, which collected tracks Elvis recorded in 1963 and 1964. Executed by a complement of studio pros in Nashville, "Finders Keepers" is a harmless bit of bouncy pop. In other hands, it might have been rendered as R&B. Here it represents the kind of unchallenging pleasure that Elvis increasingly delivered during his Hollywood years. He could have performed pleasant pop like this in his sleep (and on some tracks, alas, it sounds like he did).

"In My Way," another Weisman and Wise composition, returns to the emotionalism of "Summer Kisses, Winter Tears" but without the exotic backdrop. In the 1961 movie Wild in the Country, Elvis lip syncs this one while facing a young woman on a staircase and seeming to strum the acoustic guitar that provides his only accompaniment.

This lovely little song, only slightly longer than a minute, makes time stop. It represents the Elvis-as-acoustic-balladeer most well-known from the 1956 hit "Love Me Tender." However, "In My Way" could be a thin, crusty slice cut from that pie. It's as though the lyricists looked at the "Love Me Tender" couplet--"For, my darling, I love you / And I always will"--and decided to give the sentiment a twist: "I'll be true to you / In my way," he declares. But whether professing or qualifying his love, Elvis in these simple settings, singing without the net of a backup band, is the voice of sincerity.

"Tomorrow Night," by Sam Coslow and Will Grosz, delivers the same kind of undeniable honesty but includes added spice of a different kind. The song itself goes back to 1939. Elvis's recording occurred at Sun in 1954. After buying his contract, RCA released some of the Sun recordings as tracks on Elvis's early albums, and among the early Sun releases on RCA was "Blue Moon," Elvis's otherworldly rendering of a 1934 ballad by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart. With instrumentation so spare as to basically be nonexistent, Elvis issues a moaning croon that suggests a haunting soul trapped in limbo:

Blue moon

You saw me standing alone

Without a dream in my heart

Without a love of my own

It turns out that at Sun, Elvis employed much the same ghostly "Blue Moon" style on "Tomorrow Night":

Tomorrow night

Will you remember what you said tonight?

Tomorrow night

Will all thrills be gone?

Whereas "Blue Moon" appeared on the first full LP of Elvis's Sun recordings in 1976, the bare-bones Sun version of "Tomorrow Night" didn't see the light of day until a 1985 collection. So what is the version of "Tomorrow Night" on Elvis for Everyone! ?

For this album in its original form (as opposed to its CD reissues), RCA added overdubs to the Sun version. The full country instrumentation includes a folksy harmonica solo and backing vocals, additions that yield a seemingly new recording. Since Elvis albums didn't come with detailed liner notes or even musicians' credits, the provenance of this construction wouldn't have been available to record buyers in 1965. In any case, the overdubs work in context, not interfering with the spookiness of the king's heavily processed vocal. Authenticity meets artificiality on a muddy plain, and they call a truce.

Next up is "Memphis, Tennessee," a flawless, uptempo cover of Chuck Berry's classic about a father estranged from (spoiler alert) his little girl. This recording comes from the same '63-64 sessions as "Finders Keepers." So in addition to light entertainment, Elvis in the early '60s could still rock. He delivers Berry's narrative, surprisingly and winningly, without a touch of drama, just delivering the facts and not asking for emotion. The propulsive rhythm ends quickly, begging for repeat play, ending the wholly successful but brief first side of the original Elvis for Everyone! LP.

Side 2 begins with "For the Millionth and the Last Time." This song was penned by Roy Bennett and Sid Tepper, and Elvis ultimately recorded so many Bennett and Tepper songs that in 2002 all of those recordings were collected on a 2-CD set. There, "For the Millionth and the Last Time" joins hands with such deathless Elvis classics as "Ito Eats," "Song of the Shrimp," "Fort Lauderdale Chamber of Commerce," "Petunia, the Gardener's Daughter," and "Hail the Schlockmeister." I'm not making up those titles. OK, I made up that last one. But as you might have guessed, material of that kind led serious-minded rock fans of the '60s to write off Hollywood Elvis as a schlocker. Still, "For the Millionth and the Last Time," recorded in 1961, nimbly navigates swing-dance tempos, as Elvis croons like balladeer Roy Orbison, a fellow Sun alum.

The next song, "Forget Me Never," is the final Weisman and Wise number here. Like Side 1's "In my Way," it's an acoustic-guitar ballad written and recorded for Wild in the Country. However, this one wasn't used in the film. Elvis deftly, dryly glides around the curves of the melody, but that melody and the lyrics fade from memory the minute they're over, so it's no wonder the filmmakers opted to use the similar but far more potent "In My Way."

"Sound Advice" made it into the movie Follow That Dream, but Elvis reportedly requested that this song never be released on record. As a result, it didn't appear on 1962's Follow That Dream EP. In addition, no soundtrack LP was released for the movie. But commerce being commerce, "Sound Advice" rose from its grave to become the centerpiece of this album side. Written by the team of Bill Giant, Bernie Baum, and Florence Kaye, it's really not as bad as Elvis's distaste suggests. (Among the dozens of songs Giant, Baum, and Kaye wrote for Elvis was 1963's "[You're the] Devil in Disguise," which everyone--everyone!--loves, right? Well, as much as everyone can love anything.)

In the film, Elvis serenades both the camera and his character's siblings, as their father "plays" guitar. The music bops along while the lyrics warn against following other people's counsel, even when it's well-intentioned:

It ain't sound

It ain't nice...

Don't listen to

Their sound advice

This song no doubt bears the influence of musicals past. It might be a kissin' cousin of, say, South Pacific's "You've Got to Be Carefully Taught" (1949), which explains how prejudice results from nurture, not nature. But "Sound Advice" also feels like the kind of social commentary that rock groups were about to start offering. Consider the Beatles' "The Word," from 1965:

Say the word

And you'll be free

Say the word

And be like me...

The word is love.

Or the Stones' "19th Nervous Breakdown," from 1966: "Here it comes . . . Here comes your 19th nervous breakdown." The Kinks' Ray Davies, a master of social commentary, would sound right at home delivering "Sound Advice." And if you need further proof that the song shares DNA with classic rock, consider that Bruce Springsteen, a born pontificator, likes it enough to have performed it in concert numerous times. (What else Springsteen took from Elvis will be the subject of my forthcoming volume. . . . Kidding.)

From a different universe, "Santa Lucia" is a traditional Italian song. For his 1964 movie Viva Las Vegas, Elvis adapted Mario Lanza's 1959 recording (arranged by Ennio Morricone, no less), and Elvis's arrangement is a model of restraint. Amidst trilling acoustic guitar, barely noticeable accordion, and backup humming, Elvis demonstrates his vocal range without overdoing the sentiment.

"I Met Her Today" was written by Don Robertson and Hal Blair, who contributed many songs to the Presley repertoire. Recorded the same day as "For the Millionth and Last Time," this one feels like Patsy Cline meeting George Jones. Especially nice are the gentle piano and the contrast between deep backup vocals and Elvis's tightly controlled falsetto.

Bringing it all back to Sun is the album's finale, "When It Rains, It Really Pours." This R&B grinder was written by William Robert Emerson, whose career involved a few labels, including Sun. Elvis tried to record Emerson's song in 1954, but those takes never gelled. Three years later he, Moore, Black, Fontana, a pianist, and backup vocalists the Jordanaires made it work, all 1:50 of it. Elvis's impassioned vocal compensates for some sticky-fingered guitar. More than on any other track here, Elvis sounds like he's having a blast.

But who knows. We can't ask his ghost, which haunts this album's hall of mirrors like the Elvis hologram performing in Blade Runner 2049 (2017). Because Elvis for Everyone! was assembled by the record company, we can't expect it to reveal the artist's intentions. Instead, it presents facets or facades that we can try to interpret. When Elvis looked in a mirror, did he see any of them? Did he see all of them at once? Which ones you choose to spend time with may say more about you than it does about Elvis.