Roots and Branches of Gram Parsons

by Thomas Miller

(July 2001)

Country music has an equivalent. All the best singers, the ones who make you believe they really mean it, have a crack in their voice. Sometimes it comes out as a wild yodel and times it's just a note that goes slightly off pitch or a syllable broken in two but it's always there.

You can hear it in the voice of Jimmie Rogers, "country music's first superstar" and one of Howlin' Wolf's early influences. The meaning of his songs isn't in the lyrics so much as it's in the yodeling breaks. You get the impression that, like many who came after him, from Robert Johnson to Leonard Cohen, Jimmie Rogers understood that the line between freedom and loneliness is thin, sometimes non-existent. No matter how free and exuberant he sounds, he always detours into a few blue notes to let you know that the rambling life isn't always as good as he makes it sound. In "Blue Yodel #9," the one with Louis Armstrong, the music is mournful enough that, despite the boasts of the lyric, you wonder if maybe the life isn't any fun at all.

Jimmie Rogers' music was wildly eclectic. Pop songs, folk ballads, Jazz, Blues, novelty songs, everything that was around at the time found its way into his recording sessions. Over 30 years after he died, groups like the Beatles would be praised for covering as much ground but, at the time, he was just an all around entertainer.

Probably his most personal record was "T.B. Blues." A hybrid blues/country song that confronts the disease that was already eating him away. He tries to sound detached in both the lyrics and the performance, ("my body rattles like a train on the old S.P.") but he's betrayed by his singing every time his voice cracks into falsetto. He might try making some jokes ("The graveyard is a lonesome place/that puts you on your back, throws some mud in your face") but when his voice is set free on the chorus line, it sounds like nothing so much as an attempted laugh that he can't keep from turning into a sob.

After Jimmie Rogers, the highest position in the pantheon of country singers is occupied by Hank Williams. This time, the dread was made more explicit. Hank had his share of fun songs, but the ones we remember are the ones where he went beyond sadness. In "Alone and Forsaken," "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry," and the like, he sounded afraid.

He didn't do much yodeling, though he did a fine job on "Lovesick Blues," a song that had been around since Jimmie Rogers was alive. His singing was more straightforward, but you could still hear the feeling before you heard the notes, and when it came down to choosing one or the other, feeling always came first. Like Jimmie Rogers in T.B. Blues, Hank always sounded like he was swallowing his tears. It's a sound that'll always be a part of country music. Even today, despite country radio being exclusively the domain of artists who have more in common with James Taylor than George Jones, there's still Jimmie Dale Gilmore, who carries on the tradition admirably and even does a haunting version of "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry"

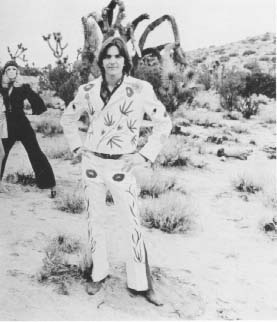

In between Hank and Jimmie Dale, there was Gram Parsons. If he'd never met the Byrds, if he'd never hung out with the Stones, if he'd never covered a Stax ballad or us a fuzztone on a steel guitar, Gram would be remembered for his pure country soul, the way his voice choked when he sang of heartbreak and grinned when he sang about the pleasures of life. He did do all that, though, and so his memory is elevated from greatness to legendary status.

There'd been a few recordings with his folk group and a couple of singles beforehand, but his first major effort was the International Submarine Band's album, Safe At Home. It's often praised as the first Country Rock album, but that title's a bit misleading. It suggests that there hadn't been any Country influence in Rock previously, which is a ridiculous assumption. Leaving aside people like Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, you still have the fact that The Beatles had been doing Countryish music since 1964. Songs like "I'll Cry Instead," and "I Don't Want To Spoil The Party," are drenched with Country guitar, thanks to Carl Perkins' influence. They even covered a Buck Owens song in 65. The Byrds can't be left out of the equation either. In the same year, they covered "A Satisfied Mind," a song also was recorded by the ISB.

What the International Submarine did was the same thing The Rolling Stones and John Mayall did for Blues. They took one of the elements that had contributed to Rock and made the connection explicit. They were a bunch of young guys who had the attitude and look of a rock band, but they put their allegiance with an older musical form. In all honesty, that allegiance is the biggest liability of the album. They never stray too far from their country roots. As a result, the cover versions are nice, but there's no reason to listen to them as long as Merle Haggard or Johnny Cash are still in print.

However, there are also four Gram Parsons originals and this is where the album becomes something special. Opening the record is "Blue Eyes," a fun song and probably the happiest thing Gram ever recorded. Life's hard and "sometimes I get down/when fancy cars go past," but he's got a pretty wife who he loves so life is good. It's possibly the corniest sentiment recorded by anyone with an iota of counterculture credibility in 1967, but everything about the record makes it believable. The rhythm section jogs along at a pleasant pace, the steel guitar has a ball filling in every available space with major key licks, and lyrics are full of good natured winks at life's troubles. My favorite is "I've got chores to keep me busy, a clock to keep my time." This is one of those records that you can't hear without smiling.

At the other end of the spectrum is "Do You Know How It Feels To Be Lonesome," a perfect song for when you've had a few beers, feel self-pitying and are certain the whole world's against you. Nothing could be a better expression of that feeling than the line, "Did you ever try to smile at some people/ and all they ever seem to do is stare."

Between those two extremes are "Strong Boy" and "Luxury Liner," the furthest the album gets from traditional country. In "Luxury Liner" the rhythm section gets a little more lively and the structure becomes looser. In a way the song is a mirror image of "Blue Yodel #9," the lyrics are about how the singer lost his love because he "made his living running round," but the music is celebratory enough to let you know he doesn't regret the lifestyle even if he does admit "If you think I'm lonely, well so do I."

While the ISB was recording their album, The Byrds were making plans for their next record, an ambitious two record set that would be a history of American music from Appalachian ballads to experimental music. To that end, they needed a jazz keyboard player, and Gram Parsons got the job by playing some McCoy Tyner influenced piano at his audition. Unfortunately, the two record set was never recorded and we can only guess what would have happened if Gram had lived long enough to incorporate Progressive Jazz into his vision of "Cosmic American Music." The only hint of what might have been was the piano break on "Wild Horses," which brings a Jazz influence into a straight country arrangement of the Rolling Stones ballad.

Wishing for what might have been, however, obscures the fact that the album they did make, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, was one of The Byrds' greatest moments. There are two types of songs on it. First there are the country songs, straightforward tributes to their roots. Then there are a few songs that go further, integrating rock elements into country songs, creating something new. Between the two, there isn't a bad cut on the album.

It wouldn't be fair to say that Gram dominates the album. In some ways, it's more of a showcase for Roger McGuinn, though Gram is the only Byrd to have any original material on the album and he has a couple of lead vocals. However, his influence is felt strongly on the album. Along with Chris Hillman, he swung the sound of the Byrds over to country music and he also presaged a hallmark of the Flying Burrito Brothers, country versions of soul songs, by bringing "You Don't Miss Your Water" to the group. Perhaps an even better indication of the impact that Gram had on The Byrds is that both McGuinn and Hillman imitate Gram's voice: McGuinn on "You Don't Miss Your Water," and, more noticeably, "The Christian Life," and Hillman on "Blue Canadian Rockies."

Originally, both the McGuinn songs featured Gram Parsons lead vocals, but there were problems with LHI, the label who recorded the International Submarine Band and claimed that Gram was still under contract with them. Once again, we're left with the possibility of what might have been. If they had been allowed to develop it, the vocal interplay between Gram Parsons and Roger McGuinn could have become as strong a signature sound as McGuinn's Rickenbacker had been a few years earlier. There isn't much recorded evidence, only a take of "Water" on the Byrds box set and an alternate version of "Christian Life" on the CD issue of Sweethearts of the Rodeo, but the thought of those two voices, both sometimes pure, sometimes ragged and yearning, intertwining on track after track is tantalizing.

Gram was also originally slated to do the lead vocal on his own "One Hundred Years From Now" but was buried under vocals by both McGuinn and Hillman. This is one of the times when they went beyond country music into a true fusion. Not only do the harmonies echo back to The Byrds' earlier hits, but the rhythm section finally breaks loose of the limitations of the genre and pounds the way a rock section should. The only other time they explore the possibilities of "country-rock" like this is on the album closing "Nothing Was Delivered." As with "Mr. Tambourine Man," and "Eight Miles High" this was The Byrds sounding like no one else in music.

While those two songs were the musical heart of the album, the emotional heart was in Gram's other original song, "Hickory Wind." It features themes that appears often on the album, nostalgia for a state of innocence, and the need for spiritual values that are touched on in various other songs. "The Christian Life" and "One Hundred Years," along with several other songs, are concerned with the same spiritual need and "Blue Canadian Rockies" looks back to an idyllic time. Even "You Don't Miss Your Water" fits, since the song is about the singer wanting something he once had but eventually lost. Considering that these were musicians who were forsaking hedonistic rock and roll for traditional, moralistic country music, what could have been a more appropriate subject for their songs?

The next step for Gram Parsons was to leave The Byrds and form The Flying Burrito Brothers. Although the music was similar, the approach was very different. In some ways, The Byrds were more of a conceptual collective than a band. Parsons, McGuinn and Hillman would bring ideas into the studio, and the others, along with a cast of session musicians, would realize them. At the playing level, there was very little interplay between the group members. Clarence White, who hadn't become a Byrd yet, plays more lead guitar than McGuinn and even drummer Kevin Kelley is occasionally replaced by Jon Corneal. Plus, there are very few group originals and no songwriting collaboration at all. Parsons wrote "One Hundred Years" alone, and "Hickory Wind" with Corneal. Perhaps that would have changed. While on tour, he collaborated with McGuinn on "Drugstore Truck Driving Man," but it's a moot point since he left the Byrds soon afterwards, even before the band recorded it.

In contrast, the Flying Burrito Brothers were a real band, they wrote songs together, they played together, and they shared vocals, rather than trade them off. This isn't a slight on The Byrds, since the Gram Parsons lineup never had a chance to congeal into a something more unified, but it is one of the things that made the Flying Burrito Brothers great, they took country music and played it with the interplay of a rock band and a rocker's attitude. Throw in an sense of music as eclectic as that of The Byrds or The Beatles and you've got something new.

Gilded Palace of Sin is one of the all time great albums, but to get better value for your dollar the best introduction to The Burritos is the A&M compilation, Further Along. Not only does it contain all but two of the Gilded Palace tracks, it also includes tracks from their second album and various outtakes of country cover versions, giving the fullest possible picture of the band.

"Christine's Tune (Devil in Disguise)" opens the CD with a forcefully strummed acoustic guitar, making the song part of a rock and roll tradition that goes back at least as far as Elvis' "Blue Moon of Kentucky." The song reveals one facet of Gram's 'Cosmic American Music' strategy; country music played with rock attitude. The steel guitar moans the high notes, the harmonies bring Lennon and McCartney back to their Everly Brothers roots, and while the rhythms might have been rock in Elvis Presley's day, they certainly weren't in 1969. Once you listen a little bit further into the song, you hear the other side of the hybrid. The lyrics aren't exactly heartbroken. As any good garage band could tell you, complaining about the girl who broke your heart is fun and can make you feel a whole lot better. Gram and Chris are having a ball calling Christine the Devil. (They later felt bad about this when Christine passed away.) After the first verse, the song goes even further into garage band territory, running the steel guitar through a fuzztone. It might sound like a gimmicky idea now, but back then the gesture tore down a boundary that seemed untouchable.

Another aspect of the band's fusion was to take soul songs and record them with country arrangements. "You Don't Miss Your Water" was a standout track on Sweetheart, but that recording paled next to the Burritos' classic versions of "Dark End of the Street" and "Do Right Woman." These arrangements are so perfect that it's hard to believe the songs were ever done any other way. "Do Right Woman" has one of music's unforgettable moments, for the most part, the song is harmonized but after a minute or so, the other voice drops out and Gram does the "A woman's only human" lines alone with the steel guitar accentuating the lonesome quiver in his voice. The harmony comes back in on "she's not just a plaything" and, finally, a tenor part joins in on the chorus. The blend of voices here is breathtaking. Urgency and beauty, tension and release, how many rock fans in 1969 expected to find these things on a country record? "Dark End" isn't quite as incredible, but it's still a few levels above the competition, alternating Everlyish harmonies with Gram's soul inflected solo lines. During the fade, Gram and Chris Hillman toss the line "You and me" back and forth like a country Don and Dewey.

The third facet of their strategy was songwriting that owed as much to the Beatles as to Hank Williams. Among all the diamonds in their catalog, the finest is unquestionably "Hot Burrito #1," later called "I'm Your Toy" for Elvis Costello's version. Over a gorgeous melody, the lyrics, simple and direct, are the finest Gram ever wrote. When the song starts out, he's bitterly trying to tell a former lover she's making the wrong choice, that she'll regret losing him, but as the song unfolds his real feelings come out and it becomes the greatest song of obsession since "Ne Me Quitte Pas." He can't help himself from admitting how much he needs her:" I'm your toy, I'm your own boy and I don't want nobody but you to love her." No matter what he's trying to tell his ex or himself, there's no question that he'd be at her feet in a minute if she asked him to come back. By way of contrast, the other Parsons-Ethridge title, "Hot Burrito #2" has little to do with country music, instead fusing gospel and hard rock. The lyrics have a touch of fatalism to them-"I love you, but that's the way that it goes"-but between piano, organ, and more fuzztoned steel guitar, the music is anything but a soundtrack for the Long Gone Lonesome Blues.

Although Gram Parsons led such a short life, he managed to travel a great distance in his music. His career can be divided into four phases. The early bands up through the ISB were his period of learning, during which time he found out what direction he wanted to take and learned his craft, writing some of his best songs in the process. The time with The Byrds was his breakthrough, when he established himself in the business. The Burritos were his moment of innovation, when he went beyond the past and created something new. The last phase consisted of his two solo albums. By this time, he had settled down into a more traditional mold. No longer tearing down barriers, he was working toward a less revolutionary, but equally noble goal: to make good country records.

That's not to say the pleasures found in Parsons' solo records are any less than those in the earlier bands. If they had nothing else going for them, they'd still be remarkable for the breathtaking vocal paring of Gram and Emmylou Harris. While not slighting the talents of Chris Hillman or Roger McGuinn, both of whom blended well enough with Parsons, Emmylou and Gram were born to sing together. Their voices created a gorgeous sound, romantic, yearning and wistful, that echoed the lyrical themes of loss and an eternal searching perfectly. On their cover of "Love Hurts" from Grievous Angel, they multiply the emotional content of the Everlys' version tenfold. The live version goes several steps beyond that. Their voices don't just harmonize, they embrace each other like a couple sharing one last dance before parting.

The solo records had more than just great vocals, though. Some of Gram's most powerful songwriting can be found on them. "Brass Buttons" is another of those heartbroken love songs that Parsons wrote so well. Although the song dates back to 1965, the lyric is extremely mature and well crafted. In the space of a single verse, it goes from concrete memories ("brass buttons, green silk, and silver shoes") to something more confessional ("My mind was young until it grew. My secret thoughts known only to a few") to heartbreaking loneliness. ("Her words still dance inside my head, her comb still lies beside my bed, and the sun still comes up without her. It doesn't know she's gone.") Even more so than "Hot Burrito #1," this song has a desolate feel that's emphasized by the fact that it's the only song Gram sings alone on Grievous Angel.

Love songs weren't all that Gram wrote. His finest melody isn't used to support another wail about the girl who got away. Instead, "The New Soft Shoe," weds a simple, lovely melody to a lyric that never says exactly what it's about but suggests a life of unfulfilled dreams, a suggestion echoed by vocals that capture the feel of a resigned sigh.. On the other hand, maybe it's just about cars and shoes. Either way, it's a touchingly sweet performance and a sonic blueprint for the sound of some of the Eagles later hits.

Elsewhere, the themes that ran through the earlier records reappear here. Sin and redemption, the attraction and cost of "the bright lights of the city," loss and regret all are explored, and that's just on "Return of the Grievous Angel." Still, the other side of Gram's music, the sense of fun that made "Blue Eyes" so delightful, hasn't been forgotten. If Parsons ever enjoyed himself on record, it was during the celebratory, Chuck Berry influenced version of "Six Days On The Road" from the live album.

As with all lives cut short, any discussion of Gram Parsons leads to

the inevitable question: "where would he have gone if he'd lived?" On the

one hand, he seemed comfortable as a country singer, and he might have

continued in that direction. On the other, he was a musical wanderer so

I don't think he could have remained a purist for long. He never abandoned

rock, as shown by the previously mentioned "Six Days," his medley of fifties

covers from the same album, and some of the live guitar work, most notably

on Big Mouth Blues. Even the pedal steel was more rock than country at

times. Beyond rock, he did a bluesy cover of the J. Giles Band's "Cry One

More Time" and the demo of an unrecorded song, "Ain't No Beatle, Ain't

No Rolling Stone" grafts Gypsy violin onto a Blues rhythm guitar. Gram

might have been a country singer at heart, but it's safe to assume he'd

have come up with a few more surprises over the years.

See the rest of our Gram tribute