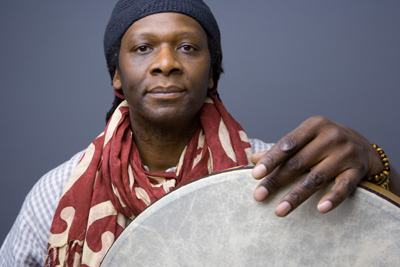

HAMID DRAKE

Photo by Jim Newberry, thanks to Thrill Jockey

Many Faces of the Beloved

by Mike Wood

(October 2010)

Horn player and mystic Wadada Leo Smith has talked in the past of rhythm as being the "Spirit Drum" of black music: independent of instrument, it is the rhythm produced which is holy anchor necessary for making music that expresses the soul. Yet it is the drums, along with bass, that traditionally provides the soil, if not the seed, of the rhythm.For over thirty years, drummer Hamid Drake has been the holy anchor for countless jazz and improvisational artists, helping to take their visions to higher rhythmic levels while at the same time carving out space within them for his own explorations. He has been one of the most consistently daring and compelling drummers around. I'm sure Drake would say that his most representative work would be what comes from his next gig, but I've chosen a few selected releases that cover a broad enough range of his playing--as bandleader, duets with specific instruments like bass, guitar, horn, etc--that will show some sense of the enormity of his achievement.

In reference to form, Drake told Ken Vandermark in a 1997 interview for Chicago Improvisors Coalition that:

"I try not to have any sort of bias towards any form because I want to be able to utilize each one to whatever degree that I can. Because I believe that all form arises from the same place anyway. The Buddhists call it "Emptiness," this "Open Space", or "Essence". People tap into the Essence and then they filter it through their own process, and because our processes might be various we come up with systems known as Jazz, or systems known as Blues, or Rock 'n Roll or Indian music, whatever it might be. I look at all those forms coming from one place, one central Essence which is an Open Space, and we just have to tap into that."

That sense of tapping into a sacred space that is available to all is most pronounced in Drake's work with bassist William Parker and with his own group, Bindu. Initially though, the key to Drake's development early on was the influence of alto player Fred Anderson (sadly recently deceased), his friend and mentor since his early 20's, with whom he has maintained a lifelong relationship.

Born in 1955 in Louisiana, Drake learned from an early age the fertile cross-pollination of rhythms as varied as jazz, blues, creole and other Caribbean sounds that flowed through the Gulf Coast. His move to Chicago in his late teens and subsequent meeting with Anderson exposed Drake to more improvisational sounds, which shortly lead to gigs with Don Cherry, and to the study of drummers like Ed Blackwell and Philly Joe Jones.

Drake and Anderson's most recent collaboration, From the River to the Ocean (2007, Thrill Jockey), draws on that lifetime of learning each others' subtleties. On songs like "Planet E," "Brother Thompson" and the title track, Drake provides a consistent but varied base for Anderson's blues-based free style. Drake's drumming, percussion and occasional Sufi chants carry their own authority while complementing both Anderson and his band, who use both Western and African instrumentation (such as the Gmbri). Of his time playing with Anderson, Drake learned a lot:

"... the lesson I got from him was that I could try to play the melodic structure on the drums the same way that the horn players were doing it. So I would try and phrase the head how they were phrasing it, and then go in whatever direction myself and the bass player would try and go. That was an incredible lesson in rhythm that Ed really taught me. (Vandemark 1997)

Having played with the likes of Anderson, Don Cherry, Peter Brotzmann, Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock, Drake has always returned to drummers and percussionists to refresh his ear and spirit. His drumming is an example of how one can be a timekeeper and a rich improviser within the same track. For Drake, it is the drummers who speak a language never spoken about among other drummers, and never explored by other musicians, but it is a language that is the most primal sound of the universe:

"I've never really seen anything in print about how percussionists or drummers might relate to each other on an artistic level: Us talking about Our language, in a sense. You always see a lot of things about guitar players and horn players and things like that, but the drum, I think in our culture, has always been like a secondary sort of instrument. We've been put in the position really of being "timekeepers" until recently. I think very seldom do the other musicians move over to the rhythmic language of the percussionists. We're always moving to their language." (Vandermark, 1997)

Drake has also been acutely attuned to the language of another artist with whom he has worked with more often than with Anderson. Similarly, William Parker has also taken his bass, like a drum usually one used in a supportive role, and explored its possibilities as a harmonic and tonal vehicle for improvisation and spiritual power. Of their many collaborations, 2001's Piercing The Veil (AUM Fidelity) is most impressive and moving. The duo incorporates tabla, shakuhatchi and assorted African percussion in addition to drums and bass, creating a meditative and yet celebratory mood. The grooves on these nine songs aim to raise awareness of the Spirit as much as celebrate its presence. Tracks like "Black Cherry" and "Loom Song" are driven by breathtaking interplay between drum and bass, while "Heavenly Walk" features both Drake and Parker on percussion instruments, each helping the other to form an intricate and muscular web of rhythm that is almost ceremonial in its feel. Drake and Parker explore their vast collective understanding of Eastern and Western sacred and secular grooves, and all their collaborations are handbooks for such a combination.

An obscure but nevertheless key addition to Drake's palette was his 2005 collaboration with Italian experimental guitarist Paolo Angeli. Uotha (NU Bop) is a live recording dominated by Angeli's prepared guitar, which produced a tone similar to the rhythmic harmonics achieved by hand by Derek Bailey. This use of the guitar as a percussion instrument allows give and take between Drake and Angeli, drawing from the latter's Sardinian folk melodies as well as improvised sections where Drake dictates the tone of the rhythm. There is a muted, silence-filled space throughout the eight pieces that fit well in a discussion of Drake's work with his group Bindu, in terms of both meditative feel and traditional grooves. In that band, Drake has been able to deepen his spiritual explorations, most significantly through his own compositions.

As a concept and a framework for the sounds explored in Bindu, Drake has said that he has a hope that musicians and artists will use their talents more often "to extend compassion to all beings so we can take fuller participation in awakening our greater potential as human potential." Clearly that is the prayer that underpins Bindu's 2005 debut (RogueArt). In Sanskrit, "Bindu" means "Subtle Point," and, as might be expected, Drake here as leader is much more meditative and hermetic as some of his other work. Drawing on his study of Sufism and Buddhism more explicitly than in other contexts, Drake extends his past work, claiming it in surprising ways, as if showing what he has learned and what he aims to now teach.

His use of tabla and flute (courtesy of Nichole Mitchell) on "Remembering Rituals" sets that stage. Other rituals "remembered" appear in the Anderson-esque free workout of "Bindu # 2," and the percussion-fueled shuffle of "Bindu # 1," which can be seen as an homage to the older drummers he has studied. "Meeting and Parting" features a strong but compassionate rhythm line, and is evocative of his give and take with William Parker.

On the closer, the almost fifteen minute "Do Khyentse's Journey, 139 Years and More," the composer allows himself some time alone with the melody, and room to dissect and reflect upon it. In many ways, this is a summing up of Drake's ideas and influences, and in a more important way, Drake shows an understanding of both sound and silence, and the holy and also humor in both concepts that would make the ancient teachers of his spiritual journey proud.

IIn a recent interview, Fred Jung (All That Jazz) asked Drake if he felt all this spiritual exploration has given him a sense of enlightenment, a "reaching on the mountaintop." Laughing, Drake said,

"Oh, no. Definitely, I don't think I have reached it and I can't say when that might be. I think we are always experiencing hills and valleys. Definitely, I haven't reached it and I hope I never reach it I always want to have room for more growth and development."

It is that humility and ongoing curiosity that makes Hamid Drake one of the most consistently adventurous and innovative drummer working today in free or straight jazz. He has both the humility and authority of a master, and the practical chops of a teacher. We will be learning from him for a long time.