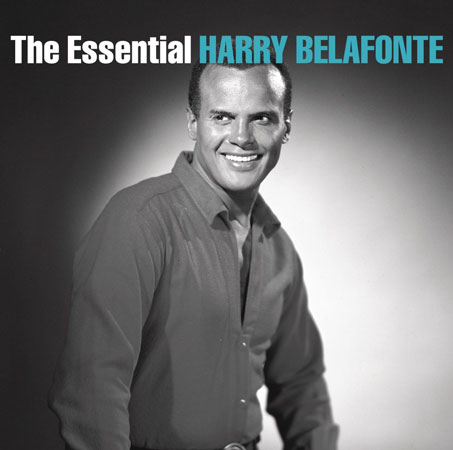

Harry Belafonte Is Essential

By Kurt Wildermuth

(December 2022)

There I was, thinking I'd already heard the greatest music ever made. Then, one gray and inclement day, I played the two-CD set The Essential Harry Belafonte (2005) and became enlightened. The best music ever made, it turns out, opens Disc 2 of this collection.

If you've been paying attention during your years on Earth, you have a sense of Belafonte as a historically important actor, activist, and humanitarian. You may know him as a musical performer. You may think of him foremost as a Black man. Whatever your sense of Belafonte, I don't have information to add to that portrait. I'm here to help spread the good news that as a singer--I mean simply in terms of vocal and interpretive ability--and as a recording artist he is extraordinary.

Perhaps I should go ahead and say "was extraordinary." As I write this, Belafonte is nearing 100 and unlikely to be at his peak as a singer. He last released a recording in 1997. In his day, though, he made so much more music than the hit recording with which he's inextricably linked, "The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)," from the 1956 album Calypso. Some of you may be able to instantly call to mind its hook:

Day-o!

Day-ay-ay-o!

Daylight come and me want to go home

A Caribbean American, Belafonte popularized calypso, whose infectiousness turned it into something of a pop-cultural cliche. Belafonte's work in that vein retains its potency, but as Steve Leggett puts it, in his review of The Essential Harry Belafonte at the All-Music Guide website: "Belafonte's versatility may surprise some casual listeners who are only familiar with ‘Day O,' and this set underscores his unique ability to find pop success with artful and socially committed material. Innovative, intelligent, and unceasingly creative, Belafonte is long overdue for a critical reappraisal."

Did that reappraisal ever happen? More to the point: Has word of the man's towering recordings reached the public? Are streaming services introducing new listeners to these songs? Belafonte's wide-ranging, groundbreaking personal and political legacy seems secure, but there are no doubt people of diverse backgrounds and ages who'd be delighted to learn that the man recorded the best music ever made.

The Essential presents over two hours of music from the early fifties through the late seventies. Produced by Belafonte and Nedra Olds-Neal, the latter of whose many credits stem largely from reissues of classics, this collection can be seen as a self-portrait of the artist taking stock and assembling details as he'd like them to be seen. Let's put aside the hagiography that normally would attend period recordings by a historically important legend. While keeping the history in mind--while doing justice to the man, the myth, the legend--let's listen as though this music is brand-new to us.

The first disc of The Essential begins, enticingly and purposefully, with Belafonte's understated and deeply soulful 1962 rendition of "Midnight Special," a traditional folk song arranged by Belafonte. This starting point anchors the collection in proletarian Americana.

A special hook here for some of us is the harmonica playing by Bob Dylan. Likewise, on a 1970 version of Ewan MacColl's "The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face," the vocals by Lena Horne are a stunning surprise. This recording comes from a TV special called Harry & Lena, which consisted entirely of these two living legends, both Black, performing before a mixed-race in-studio audience. There's currently a tape transfer of the show on YouTube, and it's worth watching if only for their spellbinding, tear-inducing duet on "First Time" and for the one-two punch of Belafonte's "Ghetto" and Horne's "Brown Baby."

The man smolders throughout the show and seems internally transported by his intense ballads. When the material fits, he doesn't just inhabit it. He seems to draw it inside himself, eerily, until it shines through, uniting singer and song. I don't think I've ever seen a singer perform this particular transformation. Method acting comes to mind as a comparison, but Belafonte doesn't get into character, doesn't make the material visible, as much as he embodies the song's significance.

On Harry & Lena, Belafonte performs "Abraham, Martin & John"--a folk-pop tribute to the late Lincoln, Luther King Jr., and Kennedy, plus Robert Kennedy. Where the song and his expression go as he processes the achievements and losses of these figures, their meaning to him, moves beyond eerie and becomes deeply moving. That recording appears on Disc 2 of The Essential.

Meanwhile, Disc 1 portrays Belafonte as a one-man United Nations, in keeping with his one-time role as UNICEF's Goodwill Ambassador. No Belafonte best-of would be complete without such tastes of the Caribbean as "Cocoanut Woman," "Jamaica Farewell," and "Man Smart (Woman Smarter)"--yes, the song later turned into a pop trifle by the Carpenters--but the man also delivered convincing live takes on the Irish classic "Danny Boy" (here so stripped-down it's nearly a capella) and the Jewish classic "Hava Nagila" (here spelled "Nageela"). If you're cringing at the mention of those chestnuts, just keep an open mind, and ask yourself if you'd rather hear deep cuts of this kind or, as on other Belafonte collections, covers of then-contemporary folk-pop songs, such as Paul Simon's "Scarborough Fair" or Jerry Jeff Walker's "Mr. Bojangles." There's nothing wrong with those folk-pop songs or Belafonte's covers; they're just less revelatory than the chestnuts here.

Disc 1 of The Essential makes a firm case for Belafonte as an eclectic artist with vocal prowess and a gift for sensitive interpretation, able to sing straightforwardly, sentimentally, or with tongue lightly in cheek, digging in for impact or gliding on the surface for fun. In terms of versatility as an entertainer and sensitivity as an interpreter, Belafonte exhibits some overlap with Elvis Presley, although rock doesn't seem to have been within Belafonte's toolkit (his attempts on the TV special don't quite cut it). For example, the busily arranged and buoyant "Zombie Jamboree (Back to Back)," from 1966's Calypso in Brass, is followed by the spare and somber "Delia," from 1967's Belafonte on Campus, where the calypso master delivers contemplative folk. Because Belafonte's later, proto-worldbeat arrangements are as tasteful as his earlier "exotic" material, there's continuity between, say, a track from 1955 and one from 1977.

"Jump in the Line," from 1966, ends Disc 1 with a pure glide, as Belafonte brings to glossy, brass-punctuated calypso the kind of high spirits that animate lively dance music, from salsa to disco to EDM. This track also suggests a dose of musical theater. In this sense, The Essentials feels like an imaginary Belafonte: The Musical, where "Jump in the Line" brings down the house at the close of Act 1. Indeed, this end-of-disc placement may tacitly refer to the recording's highly amusing use at the finale of Tim Burton's 1988 movie Beetlejuice. In 2019, in a case of life imitating art or art imitating other art, "Jump in the Line" became the closing number of Beetlejuice: The Musical!

Now, to get back to Belafonte, let's cue up Disc 2 of The Essential. The audience is back in its seats, wondering what this second act will bring. Will Belafonte dance in on a Caribbean rhythm? Will he stride to center stage and croon a meditative ballad? Instead, he does something not heard before on this collection: He hollers, "Timber!" as though his life depended on it. Brilliantly, Belafonte and Olds-Neal have opened Disc 2 with "Jerry (This Timber Got to Roll)," a 1952 recording of a public-domain folk song from the perspective of a hard-working lumberman whose mule, Jerry, has killed the boss. While ten years older than "Midnight Special," this piece shares with that one Belafonte's seriousness, bluesiness, and ability to dramatize a working-class perspective without melodrama or schmaltz. It opens ears.

Disc 1 of The Essential has portrayed Belafonte as a multilingual master of diverse rhythms. From its start, Disc 2 makes clear that Belafonte's rootsiness, his rootedness in folk tradition, his knowledge of sources, goes even deeper than that. "Jerry (This Timber Got to Roll)" qualifies as the best music ever made because of its purity. The singer couldn't be more committed to the scenario. The accompaniment--bare-bones propulsive rhythm and workers' exhalations--couldn't be more evocative yet nonintrusive. The recording couldn't be improved upon. Other music may also be perfect, but it couldn't be more perfect.

Astonishingly, though, the subsequent tracks on this disc live up to that high standard. They're different but equally great. "Waly Waly" advances fifteen years from "Jerry," to the On Campus album, and finds Belafonte adept at delivering a haunting centuries-old Anglophone ballad. The atmosphere couldn't contrast more strongly with that of the logging scenario, but the transition feels natural given Belafonte's easy delivery in both worlds.

"In that Great Gettin' Up Mornin'," a spiritual presented in a form cowritten by choir director Norman Luboff and Belafonte in 1955, picks up the tempo as singer, drummer, and Luboff's small Gospel choir passionately tell us "about the comin' of the Judgment": "Can you see the world's on fire?" whoops Belafonte in or as the voice of religious ecstasy. "Cotton Fields," recorded live at Carnegie Hall in 1959, merges other perspectives on Black culture, as Lead Belly's glimpse of rural Southern life is recast for a mellow jazz group, with Belafonte swingin', and right at home doing so, a bit like Bobby Darin doing "Mack the Knife," for the first time on this collection. "And I Love You So" brings the tempo back down and gives Belafonte the chance to croon with the control of a well-trained athlete. And so on, from mode to mode, strength to strength, through perhaps the least saccharine version of the theatrical "Try to Remember" you'll ever hear, ending with a live rendition of "Day-O," which is, after all, a comical work song.

All of these tracks were held in reserve, not included on the flashier Disc 1, to make the listener's jaw drop by the sequence. It's like you've just received your Christmas presents and now it's your birthday, an embarrassment of riches. You're thinking: Belafonte did all that and this too? No doubt, were there world enough and time, if you dug deeper into the man's catalog, if you took in its breadth, you'd find even more wonders.

Retrospectives are so often assembled in such a way that they reveal the arc of a career. Early work may show promise, the flame burns brightly during peak years, and then later work is cherry-picked. By contrast, The Essential Harry Belafonte shows the man, simultaneously from many years and many angles, always exploring with generosity of spirit. In his determined yet understated way, he pushed the boundaries of popular entertainment into self-expression at a time when doing so, especially for a person of color, was unexpected, to say the least.