Jon Hassell tribute

during a performance of "Choose Your Universe"; photo by Nicola Voss

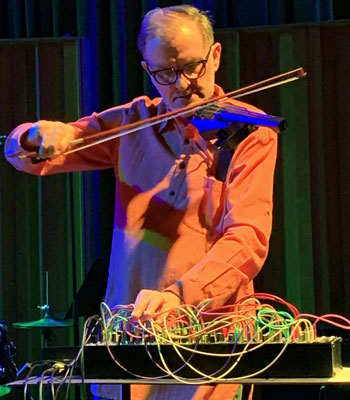

David Rosenboom

interview by Jason Gross

(August 2021)

It was in the summer of 1967 that I received a telephone call from Lukas Foss inviting me to join the Center for Creative and Performing Arts in the State University of New York at Buffalo with a position called Creative Associate. It turned out that Jon had also been offered the same position, and we both arrived in Buffalo in the fall of 1967. A part of this job was to perform contemporary music repertoire in ensembles, and Jon and I carried out that roll.

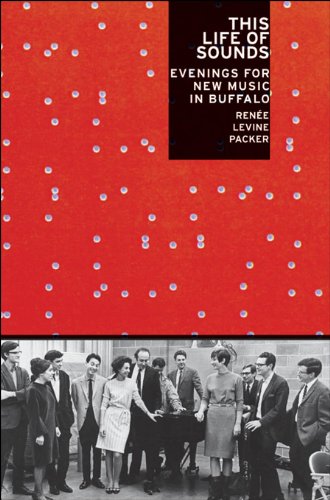

We became friends very quickly, along with a terrific group of colleagues in Buffalo. Another dimension of this job was about researching and investigating new composing and performing techniques and creating new works. Many of the Creative Associates that year were composer-performers. Renée Levine Packer wrote an excellent history of this Center: This Life of Sounds, Evenings for New Music in Buffalo, 2010, New York: Oxford University Press. There is a picture on the cover of that book showing many of the Creative Associates that includes both Jon and I. Jon is wearing a suit and tie; I have a blazer, no tie. Jon was a classically trained trumpeter, of course, and I recall a particularly good performance of him playing in Stravinsky's "Octet."

As the 1967-1968 season unfolded, amazing things happened. The late 1960s brewed a firestorm of creative innovation, of course, and all of us were a part of that. In addition to working with the Creative Associates in the Center, we met regularly in each other's homes to talk, try things out, rehearse, experiment, and improvise. The great trombonist, Stuart Dempster, also a Creative Associate, introduced us to a piece he had brought from the San Francisco Tape Music Center called "In C." Jon started expanding his work into areas of electronic music and sound art installation. I developed new forms of non-traditional notation, building unique electronic systems, writing pieces for the Creative Associates, improvising, and working with a rock band.

Maryanne Amacher and Max Neuhaus were there for a wonderful festival in the fall. It was not very long before Terry Riley came to visit and play with us. David Behrman was there, John Cage participated, and soon, we met La Monte Young. The world opened wide in inspiring new ways. Jon and I went to visit Robert Moog in Trumansburg, New York to explore possible new electronic realizations. These explorations led Jon to making beautiful electronic pieces, "Western Electric Action Pack" and "Solid State," for example.

After the 1967-1968 season, I moved to New York City and soon started working at the Electric Circus. Jon decided to stay in Buffalo one more year. As things evolved, I played with Terry Riley quite a bit, and together with Jon, joined La Monte Young's Theater of Eternal Music. In the process, Jon met Pandit Pran Nath and became very absorbed in learning from him. We also listened intensively to every new sound Miles Davis was making.

By the time of season 1969-1970, Jon had moved to New York City and started developing more sound art installation pieces, some of which I helped him realize on the technical side. My friend William Rouner and I had started a small business called Neurona Company, in which I was doing a lot of electronics development work, both in instrument building and helping other artists with technical realizations. Jon made a piece in which a horizontal surface was covered with strips of recording tape with the magnetic oxide side turned upwards. Installation visitors were encouraged to move a small plastic device over the surface, which enclosed a tape playback head that could read out the sounds and waveforms Jon had pre-recorded on the strips of tape. The sounds that resulted depended on how the installation visitors performed their movements.

In another installation, Jon buried small electronic warning devices called Sonalerts in a flower garden in front of what was then known as the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in NYC. The flowers seemed to be continuously, magically beeping. At the end of the exhibition, the beepers were dug up and placed inside plastic bags that also contained postcards. They were then attached to helium-filled balloons that took off over Manhattan, moving with the wind in a somewhat northeasterly direction. The idea was to encourage people who might find the beepers after they eventually landed to write something on the pre-addressed, stamped postcard, record where they found the beepers, and mail the postcard back. They could keep the beeping Sonalerts. I recall a particularly poignant postcard that Jon received, I believe from a children's scout group, describing how amazed the children were when they discovered a still-beeping beacon somewhere in the wilderness.

Later, Jon also tried to make a business out of selling arrays of plastic lenses that were intended to be attached to one's television screen. This device optically down-sampled the television's electronic images, making them more "cool" in the Marshall McLuhan sense. It was intended for visual recreation and stimulation at home.

In 1970, I was invited to take a faculty position at York University in Toronto to help build a music department there. It was an opportunity that would enable me to continue my research and creative work without having to depend on income from the freelance activities I had been pursuing in New York City. Needless to say, I accepted. I kept in touch with Jon though, and how he moved through various projects and eventually zeroed in on developing his Fourth World concept. This is not an easy thing to do independently, of course. I had started an ensemble in Toronto, called Light, that explored improvisation with minimal materials using gradual processes and drawing on certain developments in progressive jazz.

In 1972, I invited Jon to play with Light in a concert at the University of Toronto. Later, I felt that Jon was struggling a bit in trying to materialize his new musical direction with limited means of support. In 1976, I had the opportunity to bring him to York University for a visiting artist residency, and I acted on it. By then, my York colleagues and I had built a very nice suite of electronic music studios with good recording equipment, the York University Electronic Media Studios. This suite did not include a "standard" recording studio; but we had good equipment and a large room available in which we could set up customized arrangements of instruments and recording gear. We set it up so that we could record and play sitting on the floor, and we just started playing, for hours at a time in several sessions, with Jon giving some directions, and very importantly, leading by playing. When the residency was over, Jon took all the tapes with him back to New York and finished the project. I am very grateful to have been able to support this project [Vernal Equinox] in musical, material, technical, and hopefully, humanistic ways.

Jon was a great and innovative musician, who could clearly recognize true original depth in art, and who was fearlessly, obsessively driven to reach that same true depth in his own work.

On a personal level, Jon was a very complex, multifaceted individual. He developed strong bonds of friendship with compatible people. His creative drive saw no boundaries on personal or artistic levels, and once in a while, things might get a little edgy or uncomfortable. Still, at his core, he recognized and acknowledged the values he saw in people and was a very caring person. After Vernal Equinox, our lives took us in different directions; but on the rare occasion of crossing paths later, the depth of the friendship remained intact.

I think Jon's legacy is still emerging. These things take time. I wouldn't like to see his ideas in sound and media art overlooked. However, his unique playing and composing language, his trumpet sound, and his Fourth World ideas, which unravel traditional assumptions about musical materials and deeply incorporate complex introspections into human psyches, will remain dominant. The Fourth World idea treads on delicate terrain in our current socio-political climate that sometimes places inclusion and cultural appropriation in a complex balance of opposing tensions. I believe, though, that Jon's musical idea is innocent in envisioning a truly inclusive world that is characterized by both affirming strong individual identities and pursuing an ideal dream of cultural oneness.

Also see Rosenboom's website