HUMBIRD

photo by Dahli Durley

So much more than folkies

Interview by Edd Hurt

(February 2022)

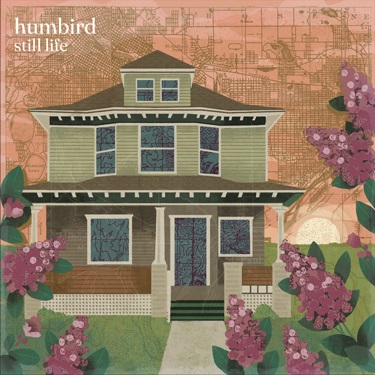

However you want to define folk music as it exists within a culture that values commercialism, it's true that adhering to some of folk's basic principles can help performers come up with innovative music. For singer, songwriter, and guitarist Siri Undlin, the basic song forms of folk are a template, not a collection of rules. On her latest full-length, 2021's Still Life, Undlin works with her band, Humbird, whose sound references electronica, jazz, and folk. Still Life is beautiful stuff that's as pellucid as a summer afternoon and as cool as a fall morning, and it's also experimental, evoking the work of such disparate figures as John Prine, Robert Wyatt, and the pioneering electronic-music composer David Behrman. In the case of Prine, Undlin directly alludes to his influence. "Pink Moon for John Prine" isn't much like anything Prine would have done, but Undlin has a Prine-like feel for the profundity of quotidian things. "I'm making new meals out of leftover food/So I can sit at the table/And stare at you," she sings.

Still Life hasn't gotten the kind of attention it deserves, but Humbird has been making its reputation by playing around the band's home in Minneapolis and hitting the road. As Undlin tells me, they played in my home city of Nashville in 2019, but I didn't catch their set. Undlin was born in Minneapolis on Aug. 29, 1991, and grew up in a section of the city called Linden Hills. When she was in middle school Undlin began playing guitar and singing at local Irish pubs. She also turned her hand to writing songs she tried out at school talent shows and open-mic nights. When she was a senior at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, where she majored in creative writing, she was awarded a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship to study folk music in the United Kingdom, Iceland, and Norway in 2013 and 2014. She spent the year absorbing music and interviewing storytellers and musicians. When she returned home, she had to decide whether to become an academic or play her music in the economically challenging world of the independent artist. She chose a path that put her on the road and in the recording studio, and she seems to thrive in both environments.

Undlin's music is singular, and it's also pretty accessible. Still Life and 2019's Pharmakon show off Humbird's ability to reassemble folk-pop in ways that sound both familiar and slightly strange. There's a strain of pure lyricism in her writing that makes compositions like Still Life's "Hymn for Whom" and "May" examples of through-composed avant-folk that amount to a variation on all-American art song. Her band, which includes drummer Peter Quirsfeld, bassist Pat Keen, and multi-instrumentalist Adelyn Strei, fills Still Life's aural space with solid rhythm-section playing that supports layers of flutes, synths, and cello. Humbird's sound is often languid, but Undlin and her band understand how to pace a recording, and how to create the kind of tension that seems like it could be a positive influence on anyone who cares to listen with the right level of attention.

I caught up with Undlin in late 2021, just after the release of Still Life.

Humbird at Icehouse, Minneapolis, November 2021

photo by Julier Farmer

PSF: What kind of music did you like when you were growing up?

SU: I was listening to a lot of what my parents were into, which I still stand by today. It was great music: a lot of the Beatles, a lot of Van Morrison, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty. I loved that stuff. I got into Avril Lavigne and Alanis Morissette, listening on my Walkman, on my headphones, on my own time--just really into those '90s women who were sometimes angry and sometimes just saying how they felt. Sheryl Crow, I love her a lot.

PSF: How did you start playing music?

SU: I was a big jock. I played a lot of ice hockey. I would always play guitar and sing for my teammates. There were some sisters on my hockey team who were Irish, and they all played traditional Irish music. We became close, and we started playing Irish music all the time when we weren't on the ice, in middle school. We would just stay up all night harmonizing and studying real trad Irish stuff, and that was also so formative. Without that, I wouldn't have wanted to go to art school. We played gigs a few times, like these seventh-graders in Irish pubs around town. It was hilarious--our parents would come hang. I started writing songs pretty early, like [at] 11 or 12 years old. I don't know that we spent too much time on those. We were more excited about learning how to play the songs that some of our favorite Irish artists were playing, and also British traditional folk from Scotland and Wales and stuff.

PSF: What was it like to spend a year abroad studying folk music?

SU: I was in Scandinavia and also in the Celtic countries. I was in the U.K.--Scotland and Ireland. I was doing a research grant, and I was pretty focused on folklore and folk traditions of storytelling, whether that was through music or oration. It was really an incredible year. I learned so much, and it was also hard to be away from home for so long and traveling that much. I had sort of been waffling between, do I want to talk about music and storytelling through an academic lens, and do I want to be in a classroom, or do I want to be out in the world performing? That year was super-determining of the decision. I still read all the time and love talking with other folks who study that work intentionally. I think in academia there's often this impulse to dissect things, which is important. But as I was doing that work that year, interviewing and trying to dissect people's answers, I was, like, with a song, what if you just didn't dissect it? What if you just let it wash over you, and you feel moved? Following and interviewing and shadowing all these artists over there really opened my eyes to how people made a living through art. The way I was raised, or how I grew up to understand, was how you could be an adult in the world. Traveling with different people and just seeing what it means to be an artist--in particular, a community-based artist--[seemed] so possible. I wanted to make a go of it, because it felt like such a profound way to spend, you know, our short lives.

PSF: How difficult has it been to make a living as a musician?

SU: It's such a steep learning curve, and I don't think it's a very transparent industry. It can be really hard to figure out how to even book one show, let alone a tour. When it comes to the livelihood side of things, I think that will continue to be a challenge. It's still a challenge today. It's hard to work two side jobs and play a show that night, and try to book tours. You might get fired from one side job and find another when you get back from the road. It's definitely chaotic--a lot of stress. But I think that's true of so many people, no matter what they're doing in this context of the American experiment.

PSF: What's your take on the meaning of folk music today?

SU: Some people are labeling music so they can more easily sell it, and so when people call something folk music, they might just be trying to package it and commodify it: this is folk music. And if you say those words, people have some idea what to expect. So it can be helpful. But I also love thinking about folk music and folk tradition in the true sense of the word, which is the music of the people and the traditions of the people, which are less about any particular sound or instrumentation. It's more about, is it accessible to folks, and does it reflect the majority's lived experience? Is it directly addressing the conditions they're living through, and is it providing solace or instruction, or community or inspiration, to the average person's life?

Also see the Humbird website