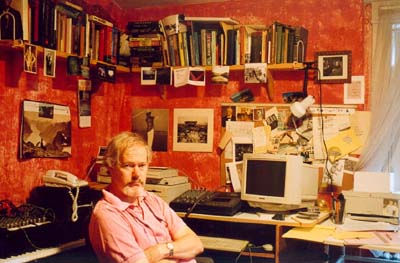

INGRAM MARSHALL

Interview by Daniel Varela

(July 2003)

More than twenty years ago, composer Ingram Marshall wrote the above paragraph regarding the problem of language and style in musical composition. Marshall has been one of the most outstanding voices of his generation, building a very personal work developed under the influences of electronic music, minimalism and sounds from different cultures. His early works are mostly based on electronic treatments of voices 2 and, after a travel to Indonesia in early seventies, he has deeply involved in a kind of works using tonal materials in a cloudish textures mixing instrumental, electronic and acoustic resources. During seventies and eighties, Marshall gave us a very consistent body of work in which beauty and construction are not opposite terms. From this period, "Fog Tropes," "Gradual Requiem," "Gambuh I," "Hidden Voices" and "Alcatraz" gained wide recognition as works in which tonal materials are combined with electronic tapestries in a very personal way 3, 4, 5, 6. Remarkably, he is a composer who is interested and committed with a deep sense of music expressiveness, a very special area of creation particularly neglected for many experimental artists 7. His attention to these concerns has driven to him to the study of several traditions, technical to spiritual, dating from ancient times. In other words, in Marshall's hands, experimental music can be related to different traditions in many forms.

This interview was done between January and April 2003 and footnotes were added in order to give more references to composers' work.

PSF: Many times, your music has been compared to late Romanticism, Sibelius, Bruckner or Mahler. In which aspect are those sources linked to your own work?

I am especially fond of Sibelius 8a,b,c and I dont know exactly why. Perhaps its the sound of his music more than anything, although he was a brilliant formalist. He seems to know just how far to go with something.

Bruckner's 9a,b music I love, but it doesn't have that much effect on my composing, although I did once base a piece on a theme from his "Te Deum." His relentlessness attracts me. He doesn't know when to stop--very different from Sibelius who, by the way, was influenced by him.

Mahler 10 affects me the least of these three. I used to like him more. His strongest works are however unavoidable. "Ich bin der Welt abhanden bekommen" is probably the most perfect song every written 11. But Mahler's sighs, his appogiaturas, are irresistible.

PSF: In what manner have you been influenced by non-western (particularly Indonesian) musics? What is your interest in gamelan?

In the late sixties we suddenly had all this "new" world music at our disposal, especially for me, Indian and Javanese as well as Balinese. I was lucky to find myself in a situation where I could study in Indonesia with teachers there and really learn something about the gamelan traditions. I sometimes uses melodies and scales that are based on Balinese ones, but they are never the exact same ones because the tuning is so different.

The long, luxurious, perfumed adagios of the

ancient Javanese gamelans still haunt me and will forever. That's an idea

in music to which I will always aspire 12.

Regarding Eastern European music, while I never studied it or got involved

as I did with Indonesian music, I have always found the folk music of this

region close to me, and yes, the lamentations are particularly compelling,

also the very close harmonies.

PSF: Your use of electronic media seems particularly sensitive regarding its manipulation of treated voices, soundscapes or clearly tonal materials. Could you comment these aspects of your compositions? What do you think about technology used in expressive ways vs. a more intellectual/tech based approach?

I never worship technology for itself. It's

only a tool and one must avoid the pitfall of always wanting the newest,

most up to date technology in order to realize one's music, because that

perfect technology will never exist. It is better to use what you have,

what you find at your disposal and make the best of it- then you are in

charge. 13

PSF: What can you say about your approach to new ways of working with tonal materials? Frequently, its possible to listen your pieces as a kind of tonality "behind the fog," with gradual changes in layers of sound and "shadows & lights." It seems that sometimes there's a kind of impressionist color in which we could find smaller sound particles.

Yes, tonality is almost always there, lurking behind some foggy veil! But what is its function? That is the question. I relate to Debussy in that I find harmonies like mood or colors and the way they relate "functionally" is not so important, although that is always there too.

The reason the 12-tone composers gave up on tonality

was that they had seen it reach its limits in terms of functionality, so

they abandoned it and came up with a pathetic, artificial construction

to take its place. We in the latter part of the 20th Century have realized

that tonality was never dead or finished, it just was on the wrong road.

There are many "new" ways of dealing with it. It is our common, inherent

language 14. The impressionist cloud

and finding particles in it, this is very interesting but not something

I do consciously. If that's your take on it, then fine!! I do love Debussy,

of course 15a,b.

PSF: And what about the "hidden quotations" of hymns and/or ethnic musics ? I've noticed that in more recent works, like "Evensongs," you've used tonal materials more rhythmically driven.

This is music I remember from my childhood, so it

is a very personal ore I mine here 16.

I guess I am a bit like Ives in my use of this stuff, although he is the

real master!

PSF: Many times, your music has been related to so-called "West coast music" which seems related (or with some family ties) to musicians like Lou Harrison and, departing from the early seventies, Harold Budd or people in the New Albion or Cold Blue catalogues. Certain composers seems connected with the idea of an static/extended ("aimless tonality" or more proper "aimless major" in Tom Johnson's word ) sense of harmony. Could you comment/discuss this point - or about the West coast sound, even when you are living in CT?

Well, I dont know about Tom Johnson's "aimless Major," 17 I don't know what that means. I would be more likely to be accused of an aimless minor.

But the California environment was very important

for me and I still feel a part of it. Where I actually live isn't so important.

I don't think I would have developed as the compose I am had I stayed in

New York . Except for Glass, all the so-called Minimalists developed in

California 18.

PSF: I heard about your writings on 18th century aesthetics doctrine concerning affections and its role where music represents emotions. I'm very interested in this point. Can you tell me about your ideas on this?

Well, my musicological interest in that goes back a long way before I really considered myself a composer. I have always thought the hermeneutics of music (was) very important. What does music mean, what does it convey? What's behind it? Does it just mean itself?

It is not surprising that I was interested in those

18th century writings about the "affections" 19

because I was attracted to music because of its power to convey

meaning and there was little discussion of that in the mid-century. The

rationalists of the Enlightenment thought they could codify all the emotions

and how they might be conjured musically.

PSF: Some of your works are related to special personal/spiritual situations, i.e. "Three Penitential Visions," "Gradual Requiem" and "Hidden Voices." Have you some special consideration about musical creation and some concept on transcendence or are these works more focused on special/particular situations?

The connection between music and spiritual matters is so obvious that it is easy to forget it. I began to understand this more after my father died and I realized that I was composing music to help me deal with the feelings of loss.

Now it is more generalized. I think the divine is

always within and creating music is a way of releasing it. Spiritual music

connections are too many to mention, or the subject of an entirely different

interview! 20

PSF: What do you think about composers more overtly related to a spiritual/religious approach to sound like Pärt, Gorecki, Tavener, and the late Goeyvaerts 21 ?

Part I like very much, Gorecki is great when he is

great! Tavener generally leaves me cold because it seems contrived, although

he has written some gorgeous music. Goeyvarts I don't know at all--should

I?

PSF: Listening to your music, I'm impressed by its sensitive quality, due to "flow / drifting"; more than a "logical" kind of process . How do you compose? Have you some formal plans before you start to write? Have you different strategies in front of a new work or is you composition more related to a relaxed/ flowing process?

I rarely pre-compose, that is, have a formal plan

in place, and if I do, it usually ends up all messed up! I tend to let

the materials seek their form, although this gets me into trouble and I

often revise a lot for balance and structure. I feel most satisfied when

the music seems to direct itself. Having some good ideas at the start helps

a lot. Overall I seek "harmony."

PSF: Could you describe your current creative period? Do you see as related to earlier stages of work? In which aspects?

I can see that I had an early period when I was experimenting but now it all seems like one long flow and I'll leave the categorization up to others!

I am composing a work for "Bang on a Can" (an all amplified ensemble) which is called "Muddy Waters," and has little to do with the blues singer. It takes off from an old American psalm tune, and the psalm (number 69) goes: "The waters in unto my soul are come, God me save/ I am in muddy deep sunk down/ where I no standing have." The music is about being low, slow and stuck--at least until the end when things lighten up a bit. Come hear it in New York in June.

Footnotes

1) Marshall, I: "Modernism. Forget it!" Soundings 11, Santa Fe, 1981.

2) Strickland, E: Liner notes to Ingram Marshall/Ikon. New World Records CD 80577.

3) Ingram Marshall: Fog Tropes, Gradual Requiem, Gambuh I. New Albion CD NA002

4) Ingram Marshall: Three Penitential Visions, Hidden Voices. Elektra Nonesuch CD 9 79227-2

5) Ingram Marshall: Alcatraz. New Albion CD NA 040

6) Strickland, E: "Ingram Marshall," in American Composers. Dialogues in Contemporary Music. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1991.

7) Johnson,T: "Avant-Gardists Reach Toward the People: Alvin Curran, Ingram Marshall, David Mahler, and Warren Burt." Village Voice, March 7, 1977. Reprinted in The Voice of the New Music, Apollohuis, Eindhoven, 1989.

"Ingram Marshall, a composer-performer from California, presented a somewhat similar continuous solo work in a loft on North Moore Street. This hour-plus work, 'Fragility Cycles,' was largely prerecorded, though Marshall also fed live synthesizer sounds into the mix, and he occasionally played a gambuh, an end-blown Balinese flute. This piece was a veritable panorama of lush stereophonic sound, with more or less continuous reverb, and it came across with a gloss reminiscent of many commercial film scores. The music moved from resonating vocal 'cries in the mountains,' to flute solos, to an electronically distorted Sibelius symphony, to processed speech sounds. Swedish as well as English texts were transformed in the adroit multitrack mixtures, and everything blended smoothly into a big, velvety piece. It was a superpleasant concert, and while a familiarity with Sibelius would have been useful, one didn't really need to know anything about music or avant-garde developments to appreciate what Marshall was doing. As I said, I don't know why avant-garde composers such as these have been seeking wider audiences and moving toward more accessible styles. Nor am I sure I like the idea. On one hand, I keep thinking about Off-Off-Broadway, about how it began around 10 years ago as a vital experimental genre with brilliant discoveries every season, and then gradually became a sort of farm-club system for commercial theatre, and I keep hoping that the same thing won't happen in music. On the other hand, I'm a little tired of hearing long, drawn-out experimental works that explore only one small experimental question, and I'm glad to see composers reaching out to general listeners..."

8a) Layton, R: "Sibelius; Finland's voice in the world." Virtual Finland, November 19, 2001. http://virtual.finland.fi/finfo/english/sibelius.html. An excellent profile written by one of the World's leading experts in Sibelius'music.

8b) Niemi, I: "Ainola. The home of Jean Sibelius." Virtual Finland, April 8, 2002. http://virtual.finland.fi/finfo/english/ainola.html. Interesting picture on Sibelius' house and surrounding landscapes for a better understanding of his musical sense of space and time.

8c) de Bode, P: Jean Sibelius (1865 - 1957). A selected bibliography http://home.hccnet.nl/p.de.bode/sibbib.htm#goss2

9a) Engel, G: "The life of Anton Bruckner." Chord And Discord. January 1940. Vol 2. No 1 A Journal Of Modern Musical Progress. Published by the Bruckner Society of America, Inc

9b) Engel, G: Biography of Anton Bruckner, linked to impressive Jason Greshes' Mahler web pages http://www.netaxs.com/~jgreshes/mahler/brucknerbio.html

10) Engel,G: Biography of Gustav Mahler: http://www.netaxs.com/~jgreshes/mahler/cdindex.html with a lot of remarkable readings in the same page (i.e.: Mahler's Musical Language, also by Engel)

11) Edward R. Reilly: Mahler, Rückert Lieder (1901 - 1902) http://www.americansymphony.org/dialogues_extensions/98_99season/6th_concert/mahler.cfm

"The poetic theme of "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen," one of Mahler's most beautiful and moving songs, is again unusual. It evokes the peace achieved through the poet's withdrawal from the everyday turmoil of the world and his absorption in the most meaningful and central aspects of his life: his heaven, his life, and his song. (By implication the last is the product of the preceding two). The comparatively long introduction, presented once more by an orchestra of woodwinds and strings, but this time with an English horn, and without the brighter sound of a flute, presents a wonderful expanding melody that moves upward from a simple two notes, to three, and then a more rapid extension to the line's melodic peak, followed by a descent that completes the arc. A variant of this descent is used again to conclude and frame the three stanzas of the main body of the song. The setting of the beginning of each stanza draws on the introduction in different forms, and in each continues differently, with the second moving further afield in order to return more clearly to the opening in the third. In its melodic development, the transparent interweaving of the instrumental and vocal lines and in the subtle fluctuation between inner tension and repose, the song represents one of Mahler's supreme achievements. At the same time it points to a later masterpiece, the "Abschied" movement in Das Lied von der Erde.

12) Strickland, E: Liner notes to Ingram Marshall/Ikon. New World Records 80577.

"In 1971 he spent the summer in Indonesia with Charlemagne Palestine, studying with K.A.T. Wasitodipura, a Jogjakartan gamelan master on the CalArts faculty. After Indian raga, the repeating cycles of interlocking modules in gamelan were the most important foreign influence on Minimalism, and while Marshall did not compose gamelan in any formal sense, it reconfirmed the viability of unhurriedness in the unfolding of the musical process and repetition as a controlling structural principle. His later Woodstone is a gamelanic retake on the Beethoven sonata of the same name, but a more significant Indonesian element in Marshall's music was his incorporation of the wooden gambuh flute into several compositions, employed somewhat in the manner of a rondo in The Fragility Cycles. The delicacy of the instrument proved to be a perfect match for the title."

13) Strickland, E: Liner notes to Ingram Marshall/Ikon. New World Records 80577.

"I could compose directly onto tape as an artist paints directly on his canvas," he explains. "That's the great advantage of tape music, the direct relationship between the head sound and the composer's work-there's no middleman." The painterly quality in his work persists to this day: Most of his compositions, at least from Fog Tropes on, might be called "tone paintings" more accurately than "tone poems" (the Straussian rubric now in its second century). Just as the propulsive music of Philip Glass seems fated from birth for the dance stage it took a decade to reach, so Marshall's often static and profoundly mysterious sonic landscapes led inevitably to a series of collaborative works, "musicovisual operas," with a photographer--his friend from Lake Forest days, Jim Bengston (Eberbach, Alcatraz).

Mention was made above of the later characterization of Marshall as a "New Romantic." His affinities in the perforce-Old Romanticism are with later Romanticism: Bruckner is a favorite for the very weightiness and earnestness that turn most listeners away. Another is Sibelius, here paid homage in the first of Marshall's "tone-paintings"- and his first piece remotely classifiable as "New Romantic" as much as Minimalist. Sibelius in His Radio Corner was inspired by a photograph of the Finnish composer during his "forty years of silence," sitting in an armchair and listening to his own work being performed on the radio. Marshall's composition, in its non-narrative depiction of the scene, complete with an allusion to Sibelius' Sixth Symphony, is an aural equivalent of the photograph. The very fragmentary nature of the symphonic allusion preserves the sense of frozen moment rather than compositional momentum, while a sense of harmonic stasis is retained despite the multiplicity of sonic events.

14) Johnson,T: "Young Composers Series: John Adams, Michael Nyman, Paul Dresher, Ingram Marshall." Village Voice, February 5, 1979. Reprinted in The Voice of the New Music, Apollohuis, Eindhoven, 1989.

"Ingram Marshall lives in San Francisco, where he has taught, written criticism, worked in radio, and directed a concert series. His contributions to the Guggenheim series were 'Cortez,' a prerecorded tape pice, and 'Non Confundar,' a work for strings, clarinet, and flute, with electronic processing. Both pieces are moody, and it is here, more than anywhere else in the series, that I am tempted to use the word 'neo-romantic.' ... Marshall works with pure sounds rather than melodic themes, and electronic reverberation rather than opulent orchestration. Still, the resulting emotions remind me very much of Sibelius, whom Marshall appreciates very much, and Mahler, from whom he borrowed some 'Non Confundar' material. I used to feel it was the electronic veneer that made Marshall's music seem saccharine to me, but I'm beginning to realize that the basic problem has more to do with my own less romantic inclinations. I probably wouldn't be swept away by his lush pieces if he did them with the Philadelphia Orchestra either. But many certainly would."

15a) Lockspeiser, E: Debussy. J. M. Dent and Sons, Ltd. New York, 1933

15b) Seroff, V: Debussy. Musician of France. (Chapter VIII Bohemian Period -- Debussy's Esthetics) Putnam. New York, 1956.

16a) Marshall: "The all too familiar hymns of my

childhood have come back to haunt me... For me the research into memory

is an important tool in my compositional workshop. We are, all of us, always

searching our past in an attempt to understand the present..."

Liner notes to Evensongs. New Albion CD NA

092.

16b) For a good account on this point, see Strickland, E: "Ingram Marshall," in American Composers. Dialogues in Contemporary Music. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1991

17) Johnson,T: "Aimless Major and Other Keys: Pauline Oliveros, Phill Niblock, Julius Eastman, Romulus Franceschini, Harold Budd." Village Voice, March 31, 1980. Reprinted in The Voice of the New Music, Apollohuis, Eindhoven, 1989.

"Some time ago, I devoted a column to 'The New Tonality' (Voice, October 16, 1978). I discussed Steve Reich, Frederic Rzewski, Brian Eno, David Behrman, Terry Riley, and others, and showed some of the ways in which such composers establish tonal centers in their modal music. Without ever departing from a basic scale, and without relying on traditional chord changes, it is quite possible to set up a tonal center or to shift between several tonal centers, and many composers now work that way. But since then, I have begun to notice a number of other new kinds of tonality and would like to define and label five of them. 'Social tonality' was demonstrated in a recent performance by Pauline Oliveros; 'slip-and-slide tonality' is perhaps unique to the music of Phill Niblock; 'slow-motion tonality' is what I think Julius Eastman is currently using; 'static-motif tonality' cropped up in a piano piece by Romulus Franceschini; and 'aimless major' seems to describe Harold Budd's approach.

Harold Budd's "Preludes" are also piano pieces, and they also seem to have quite a bit to do with Satie. Budd played for about an hour at his recent Kitchen concert, improvising on precomposed piano textures that involved major-seventh chords and other harmonies I usually associate with cocktail lounges. But while cocktail lounge pianists follow prescribed changes and orient their music toward particular keys, Budd seems to forget all about key structure and just lets the music drift. Many of Satie's pieces do that, too, but while I sometimes feel Satie was simply trying to be as perversely un-Germanic as possible, Budd's motivations seem quite different. Despite the pop harmonic language and the super-pretty surface, I would say that this Californian composer is actually a fairly extreme minimalist. Essentially, he offers no mood changes, no color changes, no tempo changes, no virtuoso licks, no climaxes, no lyrics, and no references to familiar tunes, and even the harmonic changes can take a very long time. There is something poignant, even philosophical, about the intentional aimlessness of the music. But 'aimless major' and my other categories must certainly make up an extremely incomplete picture. I suspect that tonal centers are being handled in quite a few additional ways, that many such techniques will not be well understood until their non-Western origins are tracked down, and that eventually those discussions about tonality and atonality and bitonality and pantonality and everything-else-tonality will have to be picked up and expanded."

18) Marshall: "There's much a looser environment, so a composer could more easily succumb to his or her hedonistic impulses in California, without worrying about whether he or she were falling into the proper niche of history or whatever. There's less demand to write something that's historically 'correct' and that's the big difference between the so-called East Coast academic music and the West Coast let-it-all-hang-out style. It has more to do with attitude that as actual style... " and after; "You can say there's a California school, I mean, I've given lectures in Europe on the whole 'California new music scene' but I feel in a way I've fabricated it somewhat to make it more a historical reality than it really is" Quoted in Schaefer, J: New Sounds. A Listener's Guide to New Music. Harper & Row, New York, 1987.

19) "The German composer/harpsichordist/ music theorist Johann Mattheson published a book early in the eighteenth century called 'Die Affektenkehre,' The Doctrine of Passions, in which he categorized the various keys and types of melodies according to which emotions they induced to people. Mettheson's writings were highly influential, especially among opera composers at the time" New Sounds. A Listener's Guide to New Music. Harper & Row, New York, 1987. Another interesting references about the subject could be found in Strickland, E: "Ingram Marshall" (quoted above) and for those who could read German there's an interesting Mattheson's theories review; Catenhusen,M : Rhetorik und Affektenlehre bei Johann Mattheson Universität Potsdam, Hausarbeit 12/ 2000 at URL: http://hausarbeiten.de/

20) "To find a great music deeply imbued with spiritualism, one has to look over the great abyss of the twentieth century before coming to Mahler and Bruckner. The vast spiritual emptiness of the twentieth century is well enough documented and well enough felt. Spiritual concerns in modern music are superficial at best, Stockhausen's recent excursions to the Orient not withstanding. Messiaen, the Catholic mystic, seems to exhibit his religious values in music like war decorations. With Stravinsky, religion seems to be another aspect of his far ranging theatricality. Among the Americans, only in Ives have I felt a deeply ingrained spirituality, and then it's always buried under a cornucopia of other concerns. It seems that modernism can reflect deeply felt spiritual values, but it rarely can be involved with them; it rarely can be about them." Marshall in Soundings 11, Santa Fe, 1981.

21) Goeyvaerts is the lesser known of the group for non-European listeners. A good profile of his work is Oehlschlägel, R: "Concept of a New Humanity. On the Death of the Flemish Composer Karel Goeyvaerts." World New Music Magazine No 3, November 1993. MusikTexte, Köln.