The Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus

A Vintage Bubblegum LP as Schlock & Roll Oddity

By Kurt Wildermuth

(October 2022)

For a record collector, there can be joy in finding an analog recording--a single or an LP--that doesn't exist in an official digital form. For example, one vintage LP that never made it onto CD is The East Coast 60's Rock & Roll Experiment, released in 1986 and discussed by me in a recent Perfect Sound Forever article as "a fringe time capsule."

The label "fringe time capsule" applies equally well to The Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus, a vintage LP that made it out of the analog era but just barely. This pop-cultural artifact was released by New York's Buddah (later, correctly, Buddha) Records in 1968. It was reissued on CD only once, by Castle Communications in Germany in 1993. However, for that release the title was changed to Down in Tennessee, taken from one of the song titles. So strictly speaking, The Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus has never appeared on CD.

Whatever the collection's title, you can't legally download its electronic files, if you can find them at all.

Would anyone even want to download the album?

Some of you weren't alive in 1968 or even in 1993, but you're here because you're curious and perhaps seeking oddities for your record collection. To shed light on this obscure corner, let's dig back into ancient history.

Kasenetz-Katz refers to Jerry Kasenetz and Jeffry Katz, also known as Super K Productions. From 1966 to 1977, the two JKs were music-business impresarios: songwriters, producers, promoters, hustlers. Picture two young Phil Spectors but without the eccentricity, the genius that morphed into madness. The JKs liked pop-rock, but they didn't necessarily have a talent for making it. Being on the business side potentially meant making lots of money, and success in that sense meant understanding the market.

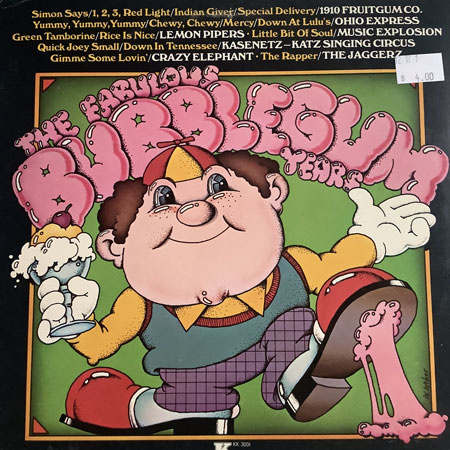

Kasenetz and Katz coined the term "bubblegum music" to characterize their principal products, which were targeted toward teenagers and other gum-chewers with expendable income. These days, if you're aware of the duo's catalog at all, you probably know some of the hit singles that so far have stood the test of time: the Music Explosion's "Little Bit o' Soul" (1966), the 1910 Fruitgum Company's "1, 2, 3 Redlight" (1968), the Ohio Express's "Yummy Yummy Yummy" (1968), Crazy Elephant's "Gimme Gimme Good Lovin'" (1969). The rhythm sections were solid, the bassists were often standouts, but the guitarists seldom soloed--either because they lacked technical ability or because the songs needed to be short so as not to overstay their welcomes.

But is this good music?

As the song titles make clear, we're not talking about Beethoven. Still, if you're tempted to snobbishly dismiss these confections and others as mere schlock, consider these facts:

--"Little Bit o' Soul" was covered in 1983 by the Ramones, as was the 1910 Fruitgum Company's "Indian Giver."

--"Gimme Gimme Good Lovin'" indulges in a brief bit of rhythmic mayhem akin to the Velvet Underground's groundbreaking "Sister Ray" (1968).

--Without "Gimme Gimme Good Lovin'" there might not be the Ramones' "Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment" (1977) or Velvet Underground founder Lou Reed's "Gimmie Good Times" (1978).

--"1, 2, 3 Redlight" was performed in concert by the Talking Heads in the mid-'70s, and their debut album, 77, could be considered bubblegum for eggheads ("Love, love is simple as 1-2-3," sings David Byrne).

--"Yummy Yummy Yummy" gave the Cars the opening chords of 1978's "Just What I Needed," which in turn gave Fountains of Wayne the opening chords of 2003's "Stacy's Mom."

In short, unapologetic bubblegum may be too sickly sweet or annoying for you, but it inspired some of the harder-edged, cerebral, or undeniably catchy music that people consider cool or coolish. Punk rock, new wave, and power-pop owe major debts to bubblegum, as do, for better or worse, many of today's hits.

Such as?

When Miley Cyrus, for one, works with Joan Jett, she is drawing on the power of a direct descendent of the bubblegum factories. Jett's breakthrough album, 1981's I Love Rock 'n' Roll, was produced by Richie Cordell, who as an employee of Super K Productions wrote "Indian Giver" and later produced the Ramones' covers of it and "Little Bit o' Soul." Jett's album was released by the Boardwalk Entertainment Co., whose founder, Neil Bogart, had headed Buddah Records and its parent company, Kama Sutra Records.

Like disco, which Bogart purveyed through his Casablanca Records, bubblegum can be depthless fun. The world would be considerably grimmer without the sunshine offered by Tommy James and the Shondells' "I Think We're Alone Now" (1967), the Archies' "Sugar, Sugar" (1969), the Partridge Family's "I Think I Love You" (1970), the Bay City Rollers' "Saturday Night" (1973). Although these tracks weren't made by Super K Productions, they share DNA with the Super K oeuvre. Think about all the shiny happy little ditties that continue to spiral out of that DNA.

Why is a grown man writing about such trifles?

Good bubblegum records unfailingly please me, exactly as they were meant to do. In a world of sickness, death, hatred, willful ignorance, economic inequity, and violence, uncomplicated pleasure can suffice as means and end.

In addition, when I hear the chugging rhythms and unchallenging rhymes of bubblegum, I don't just hear fluff. I also hear the chugging rhythms of the Velvet Underground and the unchallenging rhymes of the Stooges ("Maybe go out / Maybe stay home / Maybe call Mom on the telephone," sang Iggy Stooge aka Pop). Without those undeniably template-establishing bands, there'd have been no glam. Without glam, there'd have been no punk. In other words, trash, whether groundbreakingly hard and acidic or teeth-rottingly soft and sweet, can be treasured, whether as seminal influence or fleeting pleasure.

But if the pleasure is fleeting, does the music matter?

What matters with music like this is not what's there but what you bring to it. Like minimalism in miniature, bubblegum works through repetition, creating a drone that invites you in. You then bring your own emotion to it--though the vocalist on the "Indian Giver" single sounds as desperate as any higher-profile balladeer, so bubblegum's not all fill-in-the-blankness.

"Gimmie gimmie gimmie some good times," as Lou Reed sang, purveying a stickier gum,

Gimmie gimmie gimmie some pain

No matter how ugly you are

To me it all looks the same

Yes, to me, it all looks and sounds and may be the same. The guiding light of pop and pop-rock and much rock is a striving for release from mundane reality through simple, often secondhand, even shoddy materials. Allen Ginsberg once likened the appeal of punk to the appeal of the Beatles--and no doubt in his mind to the appeal of the Beats: artists and fans were searching for ecstasy. Same thing with bubblegum, whose artists and fans found ecstasy in two, possibly three, minutes of craft or crap or both.

Multiply those minutes by, say, a dozen tracks, six per side, and you get a bubblegum LP. The Super K Productions groups put out albums, but they weren't thought of as album artists. The groups weren't really thought of as artists except in the sense of A&R ("artists and repertory"--the label's stable). Still, Kasenetz and Katz were ambitious enough to concoct a concept album, The Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus, involving the Music Explosion, the 1910 Fruitgum Company, the Ohio Express, and many others.

Who were the others?

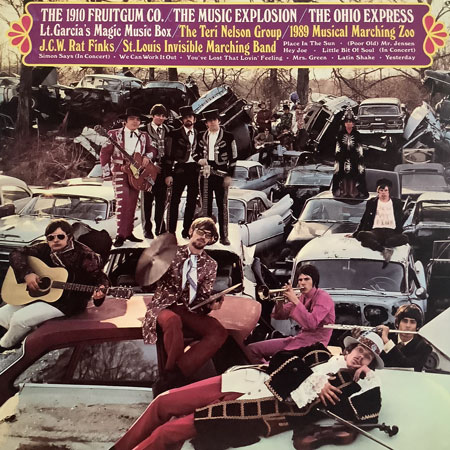

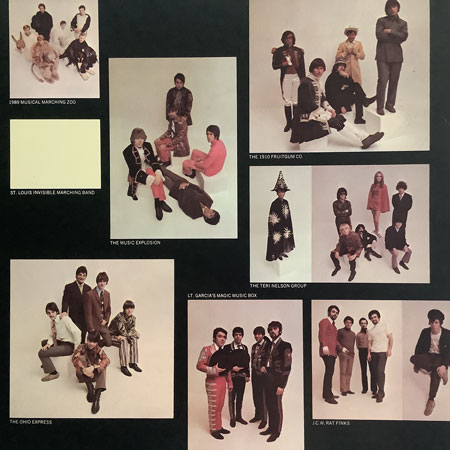

Remember Lt. Garcia's Magic Music Box, the Teri Nelson Group, the 1989 Musical Marching Zoo, J. C. W. Rat Finks, and the St. Louis Invisible Marching Band? No? That's understandable, because virtually no one but owners of The Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus remembers them. Even owners of the album would be hard pressed to distinguish one group from another or be able to match most of the groups with their songs.

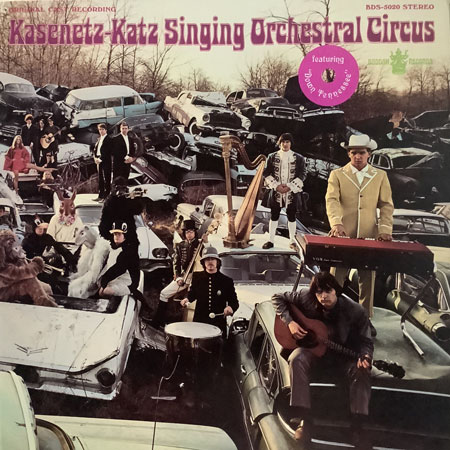

The concept of the album is that these eight groups, all from the Super K stable, performed together at Carnegie Hall in June 1968. Unlike the Beatles' fictional Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which was a single group with many musical identities, the Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus was meant to bring different performers onto one stage and onto a resultant "original cast recording," as the LP cover claimed.

In truth, no such concert ever happened. Most of the recordings on the album are obviously studio creations. Others are just as obviously studio creations that have been mixed with incredibly fake-sounding concert noise. It's hard to imagine anyone believing that even the songs labeled "in concert" are live.

The audience had to have been in on the joke, right?

Right. Plus the target audience, even if it consisted of bubble-blowing adolescents, surely understood the playfulness of the cover art. The front and back covers display landscape photos taken in a junk-car dump. Posed variously around and atop the wrecks are hipster musicians, some in mariachi outfits, some in Old English garb, some in animal costumes like the ones the Beatles wore in 1967's Magical Mystery Tour TV special. A 1968 equivalent of Photoshop has been used to place some of these people in the scenes. Inside the gatefold sleeve, band photos enable you to match the groups with their outfits, although the St. Louis Invisible Marching Band is represented by a white rectangle.

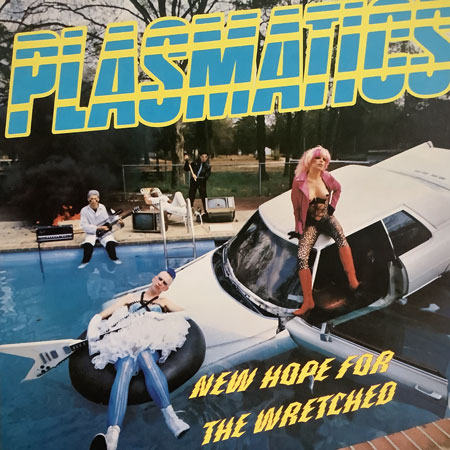

Unless or maybe even if you think it's hopelessly dumb, it's fun, even funny. As a tongue-in-cheek homage to the Sgt. Pepper cover, it's more amusing than the caustic parody of Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention's We're Only in It for the Money (1968). As pop-cultural trash, it predates the porn-punk aesthetic of the Plasmatics' New Hope for the Wretched (1980).

|

|

And yet the joke isn't as obvious as, say, the Beatles-parodying Rutles or metal-parodying Spinal Tap. The record company spent money on that gatefold sleeve. Work went into an insert consisting of glue-backed stamps that depict the various band members. Two liner notes pretend the proceedings were for real.

Record company "general manager" Neil Bogart contributes one of the notes. He describes "the wild applause of over 3,000. Some were screaming kids in dungarees and torn shirts; some were dignified oldsters dressed in tuxedos, their expressions quizzical but contained; and some were musical directors and DJ's from all over the country. . . . Colossal! Stupendous! Mind-blowing! . . . [groups] exploded into an unreal, riotous extravaganza of sight and sound. . . And history repeats itself in this sound-bursting album."

Is the album "sound-bursting"?

The album opens not with bursting sound, exactly, but with a minute-and-a-half intro. Over faux crowd sounds, the Music Explosion's lead singer, Jamie Lyons, announces the concept and lists the bands that make up this supergroup.

After a quick fade, war noises lead into an orchestral-and-choral version of the Beatles' "We Can Work It Out." Beatles' covers tend to pale next to the originals, but this one's respectable enough that it makes you think of the Mamas and the Papas with more grandiose production. Making no pretense about being live, this track was released as a single. It must have sounded sweet on AM radio.

The next track proceeds to demolish the musical credibility thus established. On "Count Dracula," the titular character speaks for a minute and a half about world domination, somehow involving Batman and Robin.

We're on surer footing with the pure pop of "Place in the Sun," wherein surf-poppers Jan & Dean meet folk-rockers Simon & Garfunkel. The immense amount of echo here makes this track a forerunner of the indie-pop/rock group Animal Collective, who like to drench pretty melodies and propulsive rhythms in cavernous reverb.

Then, amidst more war noises, Jamie Lyons spends thirty seconds introducing an odd yet unobjectionable version of the Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling" Easy-listening flutes make clear that this rendition will eschew the drama and majesty of the original (a Phil Spector production). Under the influence, you might think the original was being played on a cheap record player in an aircraft hangar.

"(Poor Old) Mr. Jensen," next up, is pure orchestrated-choral pop. The Doors and their L.A. compatriots Love were employing baroque arrangements of this kind at the time, though here you have to work to find the really lovely melody. This track, by the way, became the B-side to one pressing of the Kasenetz-Katz Top 25 single "Quick Joey Small (Run Joey Run)."

"Quick Joey Small" stands as a masterpiece of bubblegum as fake garage rock with a debt to soul; an imaginative arrangement; a winningly, edgily nasal vocal; throbbing bassline; and chirping backup vocals. The two-and-a-half-minute track's cheap production adds to the sense of menace as the singer warns escaped convict Joey to run for his life. The original even beats the nominally heavier 1978 version by the English punk band Slaughter and the Dogs, acolytes of glamsters David Bowie and Mick Ronson.

Alas, the original Kasenetz-Katz single didn't make it onto The Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus. Instead, the next year it became the partial title track of a follow-up album, Quick Joey Small (Run, Joey, Run) / I'm in Love with You. This truly studio LP is credited to the Kasenetz-Katz Super Circus, but it includes a track called "Let Me Introduce You (To the Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus)." The overlapping names are tricky! Confusing! Playfully self-referential? Or just a slapdash use of a leftover from The Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus?

Whereas that first album, the faux live one, is deliciously, cryptically evocative, the second one is simply 25 minutes of mediocre pop-rock made to cash in on the single's success. Nothing on it is as intense as the best moments of Singing Orchestral Circus or as inspired as "Quick Joey Small." Luckily, that track can be acquired on its own or on bubblegum compilations.

Also on such compilations is the single "Down in Tennessee," which closes side 1 of Singing Orchestral Circus (and is advertised on a cover sticker as "Down Tennessee"!). Imagine the Beach Boys' ultra-nerdy "Be True to Your School" recast as ultra-lo-fi garage rock with Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs' evergreen "Wooly Bully" as presiding spirit. The result doesn't suggest that anyone involved ever set foot in Tennessee.

Side 2 starts with circus noises, as Jamie Lyons returns for another minute and a half. Introducing the Music Explosion's "Little Bit o' Soul," Lyons actually dedicates the performance to Kasenetz and Katz, who were no doubt having a good laugh by celebrating themselves as living legends.

After a quick fade, the band's "performance" turns out be the first of three songs meant to seem live in concert. All three are studio recordings mixed with crowd sounds. In addition to massive echo, "Little Bit o' Soul" and 1910 Fruitgum Company's "Simon Says" feature enthusiastic handclaps, as though an auditorium full of people were singing along to the records.

"Latin Shake" makes more-inventive use of the sonic muddle caused by the crowd and chorus. Mainly, you can make out the bass playing a repeating pattern, a vocalist or two saying "shake," and organ. Early Philip Glass comes to mind, as does the psychedelic gospel stylings of the alternative-rock band Spiritualized.

"Mrs. Green" returns us to the studio--not that we ever really left. Like "(Poor Old) Mr. Jensen," this track dabbles in Old English sounds, punctuated with flute and harmonizing monks. The mix is pretty much mud, but there's another nice melody if you can find it.

While previous tracks have displayed real craft--even seriousness of purpose--beneath the plastic surfaces, "Hey Joe" solidifies the sense that this album is a trip and is meant to evoke one. The repetition and drones in previous two-minute bursts haven't prepared us for the full-on acid rock here.

The aforementioned Love had done a fast version of this song, as had their L.A. compatriots the Leaves. The Jimi Hendrix Experience had slowed the tempo considerably for a more soulful groove, as had Johnny Rivers. The Kasenetz-Katz version suggests Love and the Leaves crossed with Hendrix and Rivers but at an even slower tempo. Drums kick in for perhaps the first time on the album, but everything is so drenched in echo that it's impossible to make out what's being said or even that it's being said to Joe.

What's left? What's "Hey Joe" without the singer asking, "Where you going with that gun in your hand?"

What's left here is the feeling of being in a mind-bending atmosphere. Then the smoke clears, the way the sonic mental landscape shifts in the Talking Heads' "Memories Can't Wait" (1979). On the T. Heads track, distortions, curtains of sound effects, part to reveal a garage band. On this one, the murk moves out and exposes just bass in space, punctuated by fuzz guitar.

Suddenly you're dreaming. "Hey Joe" is playing really really loudly over the sound system of a smoke-filled rock club in 1968. In the crowd, dancing, grooving, are the Yardbirds, the Animals, the Stones, Jefferson Airplane, and at least one of the Beatles. Let's say it's Paul. The DJ spots Paul, and the next record on his turntable is an at-first unrecognizable and then quite pretty version of "Yesterday." The DJ must be fond of things American, though, because this track sounds like a Glen Campbell country-pop single given the orchestral-choral treatment. This version assumes that you know the Beatles' song. You're being reminded of it in a dream.

The dream ends, as the Kazenetz-Katz album does, with "All Gone," which is less than a minute of war noises, maybe animal sounds, a trumpet playing taps, underwater gurgling . . . apocalypse.

What does the album add up to?

Not much. Some fun, especially in the packaging. Ultimately, a bad trip. What fascinates me about The Kasenetz-Katz Singing Orchestral Circus is simply that it exists.

As a concept album, Sgt. Pepper it ain't. As a stylistic hodgepodge, the White Album it ain't. As a concert recording, it just ain't.

What did its creators really think of it as?

"The end result," write Kasenetz and Katz in their own liner note, "is a rare blend of the probable and improbable: a brand new sound that excites and pleases a variety of wildly different tastes. . . . All we can say in conclusion is . . . enjoy!"

We make choices about what to do with our limited time. Some of us become musicians. Some of us invade sovereign nations, killing and injuring and destroying, altering the world for the worse. Some of us aggrandize ourselves at the expense of democracy. Some of us appreciate pop-cultural artifacts in all their strange and unexpected beauty. For this album, Kasenetz, Katz, and their crew labored on a half hour of oddball play, surely for money but seemingly for the heck of it.

Fair enough, but wait a minute. Are you saying the Velvet Underground and the Stooges are bubblegum?

Sort of.