Lena Zavaroni

Alternative UK pop & Spike Milligan

by Luke Aspell

(March 2011)

There's nothing else this space is pretending to be; there are curlicues like rococo shapes in a waiting-room carpet, solid but refusing to coalesce into the representation of a conceivable structure. Apple-juice weak green light, a shade owed to the particular medium, and white walls leading unbroken forward. It does not intend to be taken for anything other than a television studio. It is a no-place, of the same family a little later in time as the void in which the Black and White Minstrels capered. This is where the show Lena took place. There is no line that reveals the venue in which this space has been contrived the reverse angle would be hard to conceive from the evidence of what we see, though we will of course make an educated guess, quite without realising it.As the fallout of Thatcherism has curdled the self-respect of the talented amateur into a delusional frame of mind conducive to the development of histrionic personality disorder, no one who was not around at the time feels confident enough of its 'air' to claim they feel the absence of a tradition in working-class show business that is as distant, and as difficult to reconstruct in the mind as the epoch of the parlour-ballad, a tradition in which Lena Zavaroni appears as a figure of terminus: light entertainment.

Now there is the American Idol/Britain's Got Talent/X-Factor hydra, and winners whose victories are good for a hit single, a tour. The late Lena Zavaroni was a child singer and television star and recording artist from 1974, the year of her victory on Opportunity Knocks, until the effects of anorexia nervosa made the continuation of her career impossible. It wouldn't be long to manifest itself after this next appearance we'll explore. It's 1981, and already Zavaroni is finding it difficult to conform to the shape made for her in this marketplace, as that ecosystem is finding it difficult to map the desires it has the capacity to model onto the mutating world outside. Britain's silhouette is becoming foreign to itself, as the aspiration to imitate an imaginary America of cuckolding, nylon-endowing GIs is guttering in the presense of an appalling reality.

'Light entertainment' was a genre of television centred on the music-hall variety tradition, but the music of light entertainment at the height of its cultural autonomy bears little audible relation to that demotic tradition. It was a music of pit-bands whose members wore uniforms, a pale European reflection of swing, the last trace of British dance-hall culture, with guest spots for the nicer, shyer pop stars (Gilbert O'Sullivan, pre-avowal Elton John, wilderness-years Scott Walker). Light music, light comedy. Above all, it was show tunes, or the aggressive appropriation of new pop songs as such.

The music of light entertainment was cross-promotion its home is not the gig or the record, but the television appearance. In recordings by light entertainment stars, there is always an absent referent. In light entertainment, all songs are 'numbers.' Its aspiration was equidistance; it could be intimate with nobody.

In light entertainment, a song still sounded like something broken into it was melodrama taking flight, or high spirits. It was not personal expression; it could be the expression of a personality, but not the singer's own. When singing on those recordings that first established her as a television and a recording star, Lena Zavaroni's performances tended towards the mannerist how could they not? A central component of her appeal was the prodigious quality of her performance; she was, as was said, a little girl with a big voice. Andrew O'Hagan's novel Personality examined the social oddity of Zavaroni's relation to the culture of her own generation, but the really arresting oddity is that of a culture that needs this particular kind of comfort.

One can scarcely imagine it being sought now, the ideal Zavaroni represents. The work of Zavaroni begins as the pre-sexual rebirth of the pre-sexual love song, a performance of innocence. At first, she sang in a brassy tradition, a tradition of port cities, from imported American records. These songs became, in performance, a folk tradition of detournment. They formed an alternative language of utopian emotion for the working-class in Scotland and the North of England, particularly for women; this tradition is depicted in the earlier, autobiographical films of Terence Davies. They claimed the emotions of these songs to express their own. Lena Zavaroni was a little girl with a big voice. It was important her performances dramatise her improbability.

A feminist writer, informal in the sororal relation of shared oppression, would call her Lena; I cannot.

Her first single, "Ma! (He's Making Eyes at Me)," obscured by layers of retrospective ironic dubiousness, a great laughing-stock of later viewers who would never wish to spend enough time with light entertainment to discover why it feels safer to be repelled by it, is not of itself very interesting except as the prototype of a process. The song was a period piece, precisely the kind of sentiment that could only work in a novelty context, and this kind of material formed a recurring strand in her earlier albums. It is by listening to what Zavaroni's interpretations meant to songs still 'in reach' to her listeners that we can best understand the gulf between this entirely separate music culture and the British pop scene into which it occasionally bumped to mutual bemusement.

Take the version of "River Deep, Mountain High" that closes her first album, Ma! (He's Making Eyes at Me), for example. The bass introduction becomes a Pearl & Dean (ad company) standard brass fanfare, the beat galumphs rather than gallops, the production seems, paradoxically, despite being more modest in scale, overburdened in a way that the original isn't. Zavaroni's voice is something offered for evaluation in view of her age rather than something justified on its own terms; there is breathlessness that seems unmeant, there are changes of pitch that jar, but it is the selection of material that reveals the blasι quality typifying the sensibility of light entertainment music. Old-fashioned songs recuperated by recontextualisation as childish sentiment are one thing; this song seems to have been chosen for its 'big finish' value, its earnestness, and its age-inappropriate lyrics. For her minute precociousness to carry on record, the singer must be dwarfed by the song, caught breathless on occasion.

Earlier on this album, there's a recording of "Take Me Home, Country Roads." This would never have happened to fellow Scottish child singer Neil Reid, and it's what makes Zavaroni both more and less interesting. She exemplifies light entertainment's use of the song as something to be sung, something to fill space, something to kill time, whether it be John Denver, Andrew Lloyd Webber, the Eagles or George Gershwin. It could almost be said that it is the way the individuality of the different material is extinguished that makes each interpretation distinct. At this point, at least, there isn't a great deal of range in what Zavaroni is doing.

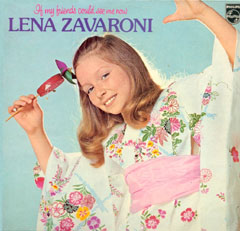

With the next album, 1974's If My Friends Could See Me Now, an attempt at particularity begins to become discernable, the songs considered as texts for interpretation, notionally. Choices are heard being made in the performance, phrase by phrase, in a way seldom detectable in the first album.

Her version of "What a Wonderful World" is perhaps the only one to approach Louis Armstrong's for subtextual heft. The song's implicit melancholy is not present in Zavaroni's reading, which makes it perfect as a simplified, broad-brush, TV tie-in comic strip adaptation Louis Armstrong decides to be happy while Zavaroni pretends to be. The curious listlessness of the accompaniment recalls concentration-camp orchestras, while the distant transistor thinness of the arrangement's presense in the mix reminded me queasily of the shipboard entertainment of the early scenes of Voyage of the Damned, produced by independent telly mogul Lew Grade, and remarkable as perhaps the only film to succeed in making the Shoah banal. On the last repetition of 'what a wonderful world,' Zavaroni adds the growl to her voice. The last-minute reach for vitality is bathetic, falls short, as wan as what surrounds it.

These mannerisms were phased out as she got older, and as fewer people listened the backings improved. A look at the record covers is also instructive. At the point of adulthood the point in time around which this performance took place the poses change instantaneously from a suggestion of precocity to a mime of the neuter. The opening song on 1981 LP, Lena Zavaroni and Her Music, a disco imitation called "I Am," exemplifies the big, clean sound of her maturity. There are almost Celtic notes in this song. The genre is transatlantic, then-nascent sweeping affirmation. The triumph of the will that seems to have been intended is undercut by the strange dependency expressed in the lyrics. This is a second-person account of a past encouragement. 'I had been waiting for someone to approve/you said 'That's foolish, you know just what you should do.'

There is no room for anything as utopian as that cessation of self-judgment that real disco prescribed. 'Look now, deeply/into the mirror/see what you find there/judge it fairly.' No stage following this searching moral inventory is described. Or perhaps the opening line is the key of the song, of the oeuvre- 'I was hiding, here within an empty room.' The producer is now in network marketing.

The biography on one fan website begins its narration in the present-tense, and this is as it should be to be a fan of her music is to engage in a kind of archaeology more perilous than mere oldies-fandom, closer to the activity of the character Francois Truffaut gave himself to play in The Green Room. The enthusiast must embrace an intimate kind of tragedy. What happened to Lena Zavaroni was not the sort of iconic neglect, cinematic and isolated, associated with singers such as Billie Holliday or Judy Garland. Zavaroni died of a chest infection related to pneumonia at the age of thirty-five. This infection was acquired during a long hospital stay to recuperate from the effects of an operation requested by Zavaroni in an attempt to alleviate her mental health difficulties. It was something close to a lobotomy.

It is 1981. Upstage, a man walks in from stage right. His dress is a fairground-mirror stereotype: a long skirt near to the floor, a broad tam. He is singing in a silly voice, parody-Scottish. He approaches the audience and the camera. It is zany British comedy legend Spike Milligan.

Lena bounds into shot and creases at Milligan's havering and costume. Cut to a close-up of Lena. Her laughter is a smile and a rustling mime, her hand flattened against her chest as though to brace herself against so much laughter. Her costume is powder-blue, with a sequinned jacket. Nothing had befallen her accent.

This is the flotsam of popular culture, washed up on the digital beach, generations from the initial source recording, let alone the transmission master. What kind of video is it? 1-inch C is the glare of a starched shirt, the buzz of broken blood vessels, the noise of a red plastic cup on a dark grey desk. 2-inch Quad is the delicate pink of a shell, a blue too light to be perceived in direct light, a Paisley pattern in the upstage shade. An expert on the period has informed me that during this series 1-inch C came in for some episodes. On the basis of such a compromised rendering, I daren't hazard a guess which was used on this episode.

Comedians don't look like Spike Milligan now. There are shadows beneath his eyes. His skin is pale and shiny. His clothes seem to have been chosen for comfort, and are unimaginable as the property of a costume department. Milligan saw himself primarily as a writer rather than as a performer and he looked like one. Comedians don't work for so long now without becoming 'legends', de-fanged and denied real work.

Spike Milligan, referred to at the time of his death as 'the godfather of alternative comedy,' started as a trumpeter, and always retained vestiges in his work of the showbusiness traditions of the era in which he began his professional career. By the time of his last broadcast series, There's a Lot of It About, the year after Lena aired, it was perhaps only in his work that the trace of that form could still be detected, not as nostalgia but as opposed orthodoxy. Milligan and his figures frequently sing snatches of songs his younger jazz-musician self found corny: "A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody" is one such, sung here by Milligan in a high Goon vibrato, his arms outstretched. His fixation on the war is well-established, but he continued fighting a culture war too, even as his work spurred others on to complete the victory, a more knowing incarnation of that stranded Japanese soldier, or Ben Gunn.

Comedy then always had to form part of a broader diet of entertainment; think of the musical interludes and romantic diversions of the Marx brothers' films. Consequently, Milligan's sketch shows generally retained a serious musical interlude. Serious because expressive of his sensibility. In later episodes these were often written and/or performed by Milligan, sometimes in collaboration with the writer of the song he is singing with Zavaroni tonight, Ed Welch.

Seen now, these interludes are a kind of catalogue of occluded traditions, linked by an air, a view of craft. Scholarly smiling folk singers; bands with lead talkers and euphonium players; Stan Tracey; the kind of song Lena and Spike will be singing for us soon. But first, a little banter.

'Tonight is the anniversary of Scotland's worst joke, and Scotland's only Jewish poet Rabbi Burns.'

'This isn't Burns's night!'

'It's not Burns Night? You mean I gave myself all these burns for nothing?'

Milligan, Irish, but really English, and originally Indian in the sense that Rudyard Kipling was, points up the strangeness of plural identities. Not merely to be different things in parallel, but to be more than one thing, all the time. Zavaroni, Italian Scot, marginal in a marginal society, performer in a tradition of numbers, at home as all are at home in a culture of imitation, none the full shilling, but without exchanging specificity for universality, all with identities intact, identities that have not been dissolved, or trained across the framework of an accustomed falsity, engaged in the work of disappearing in and out of songs, works with a different meaning in this passing context.

Beyond the timeframe of this fragment lay another artefact of unresolved identity. Also appearing on this show were Sheeba, Ireland's 1981 Eurovision entrants with their song "Horoscopes." After a fiddle-and-vocals introduction this turns into an atheist disco song about free will, mocking and dismissing superstition. Meanwhile, at the furthermost edge of the United Kingdom of which Milligan has not been a subject since the 'sixties, the people of Fermanagh and South Tyrone are enjoying the brief incumbency of their MP, Bobby Sands, another hunger artist. In just under a month he will be dead. Last Saturday, the Brixton riot started. What happens to the equidistant when the audience divides?

The title of the song is 'Woe is Me.'

Piano, drum, bass. Lena and her guest begin their song. The song bounces along in a way that subsumes a notion of funkiness without acknowledging that rock and roll has happened.

They begin to sing.

'Just tonight,

I kinda feel uptight

I got the whole thing on my mind...'

But Spike Milligan has little voice. He carries the tune, though seems to change his mind about how to handle it as he goes along. He is singing so that the song will be heard, not so that we will hear his voice. On occasion they seem to be singing different lyrics, and they sing the whole thing through together, Milligan's occasional jokey yeah-yeahs and mugging providing the only differentiation. This is a hand-made sort of song, its narrative off-kilter in this environment because it is quotidian; it is about a nervous, disappointing date. Pleasant, catchy, and accompanied rather than embodied by the introduction of the show's studio orchestra, this cannot turn into a number. For this to work as a duet, Zavaroni's voice must be reigned in, she must sing along rather than fly out.

'Woe is me,

living in a grand illusion,

woe is me...'

Milligan was around sixty-two when this performance was recorded. Zavaroni was around seventeen. Milligan would live for another twenty-two years, Zavaroni would live for another nineteen. The memory bank from which Milligan's work draws containing all the sorrow and terror of modernity, his series' status as art is as assured as that of anything made for broadcast can ever be, and assuredly little-seen now. Zavaroni's work, disturbing in different ways, has become something worse than neglected; specialised-in for the wrong reasons, corralled in karma corrido karaoke, enlisted in struggles with recapitulated grief faint shadows of the struggle underlying it. It is to be heard by everyone, and then disappear.

(Thanks to Louis Barfe)