Wings Takes Off - McCartney Nears the Ditch

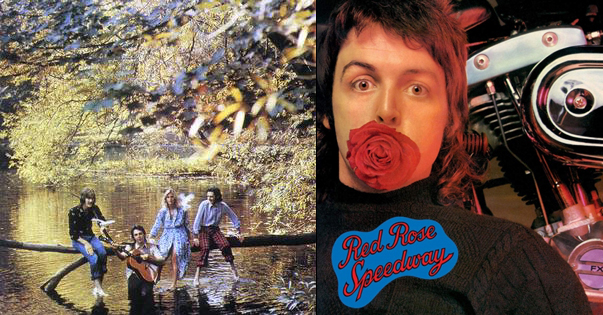

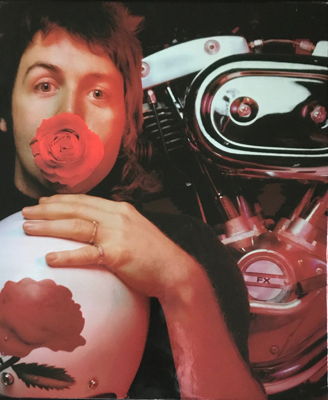

Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway

By Kurt Wildermuth

"I'm in awe of McCartney. He's about the only one that I'm in awe of. He can do it all... And his melodies are effortless, that's what you have to be in awe of... He's just so damn effortless." --Bob Dylan, Rolling Stone interview (2007)

The albums Ram (1971) and Band on the Run (1973) are now regarded as twin peaks in at least the early part of Paul McCartney's post-Beatles career. Sandwiched between those peaks are Wild Life (1971) and Red Rose Speedway (1973), albums that since their release have been regarded as, to put it mildly, lesser efforts.

Ram was credited to Paul and Linda McCartney, but Wild Life inaugurated a new band, Wings, wherein the McCartneys and the Ram drummer, Denny Seiwell, were joined by the guitarist/singer Denny Laine. For Red Rose Speedway, the guitarist Henry McCullough came onboard too. By Band on the Run, Seiwell and McCullough were on the run from the band, which had never struck many people as a legitimate ensemble. On Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway, Wings came across as a McCartney vehicle struggling to take flight.

If you're not a McCartney devotee, you may have heard only one song from Wings' first two albums: "My Love," the hit single from Red Rose Speedway. Even if the title doesn't ring a bell, you may recall the immortal lines "Wo wo wo wo / Wo wo wo wo / My love does it good." They're not the best lyrics ever written, but they're also not the worst ones McCartney ever wrote. His devotees often bestow that honor on these repeated lines from "Bip Bop," the second song on Wild Life: "Bip bop bip bop bop / Bip bop bip bop bam" (for my money, 2018's "I just wanna fuh you" is worse because it's charmlessly, witlessly both vulgar and coy).

What's going on with this drivel? Whether you love, hate, or greet with indifference the soft-rock balladry of "My Love," you have to acknowledge that McCartney makes it work, on his terms (as opposed to say, Beethoven's), through sheer craft. The melody seems like it could have come only from McCartney--the songsmith of "Let It Be" and "Maybe I'm Amazed," but with the brilliance turned way down--or like it existed forever and he snatched it out of the collective unconscious, sort of the way he initially wasn't sure where the melody of "Yesterday" came from. His commitment to the sentiment of "My Love," his determination to make the musical expression of that sentiment stick in the listener's head, is undeniable. Throw in atmospheric production, an underlying drone that suggests fog rolling across a meadow or artificial smoke filling a stage, a soaring if occasionally off-key vocal, and a stinging and eloquent electric-guitar solo by McCullough, and you have the stuff that an ex-Beatle has chosen to make his stock-in-trade for over fifty years.

By contrast, consider the craft in "Bip Bop" and you'll most likely find crap. Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway may be twin sloughs where McCartney's craft meets crap. Whether you find his particular combination of craft and crap worth exploring depends on lots of things about you. I'm not here to argue that you should explore these records. But whether you like, loathe, or are unaware of anything else McCartney has done, there's a chance you might find something interesting in his messes. For example, I know a person whose interest in McCartney extends no further than "Temporary Secretary," a song from his one-man-band effort McCartney II (1980) that strikes some adventurous listeners as ear-pleasing technopop and many other listeners as annoyingly repetitive, whiny, execrable garbage. Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway present similar dividing lines. So I'm here to tell you about the experience of hearing these albums, in case you might be tempted.

One way to make that experience more rewarding is to think in terms of two artists whose work isn't normally associated with McCartney's: Neil Young and Bob Dylan. Another way is to think about an artist whose work is inextricably tied to McCartney's: John Lennon.

The year after Wild Life came out, the Harvest album made Neil Young a big star. While sailing and selling on the success of the undeniably catchy single "Heart of Gold" (which might be considered Young's version of a "My Love"), Harvest brought together various not necessarily coherent ideas and sounds. Such assemblage has become Young's stock-in-trade through a long and ragged career, and on the way to that anti-style he responded to Harvest's success by plunging into the stardom-avoidant misery bath of his now-venerated "ditch trilogy": Time Fades Away (1973), On the Beach (1974), and Tonight's the Night (1975). "Heart of Gold" put him "in the middle of the road," Young explained in the notes to his Decade compilation (1977). "Traveling there soon became a bore, so I headed for the ditch." On the ditch albums, not just the music but the very act of music-making seemed to reflect the performer's charred emotions and disordered state of mind.

It'd be over-the-top to claim that the seemingly simple confections and sometimes fragile structures of Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway add up to a ditch duo, as if being low on artistic gas equaled visionary mess-making. Still, to think about Wings' first two albums as McCartney's getting close to the ditch, playing in dirt, digging around for pop-rocks, is to recontextualize these recordings as the work of making 'art,' even if the results don't necessarily deserve to be called art. Less so than on McCartney II and its one-man-band predecessor, McCartney (1970), but more so than on his most professional productions, McCartney here lets the seams of his work show.

The inspiration for Wild Life's rough-hewn-ness, he claimed, was Bob Dylan's quick recording methods. Go into the studio and see what comes out. Why McCartney, such a once-bright star in the musical firmament, but at this point on the defensive as lightweight and tragically unhip, would take that rough-riding approach with a brand-new band and a small batch of not-top-notch songs is an open question. Did he deserve to? Was the experiment worth his listeners' money and time?

An uncharitable view would be that ego told him, as it sometimes tells Dylan and very often tells Young, that any tossed-off junk from him would do. The fragments, raw instrumentals, and minor compositions of McCartney, his first full-fledged solo album, pointed in that direction, and Ram could be seen as junk redeemed through more-effortful songwriting and an emphasis on studio polish.

Maybe this offhand approach wasn't a plight, though. Maybe McCartney was uncynically engaging in the kind of demythologizing that fueled John Lennon's first full-fledged studio solo album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970). "I don't believe in Beatles," Lennon had sung on that album. "I just believe in me / Yoko and me / And that's reality." In explaining those lines at the time, Lennon told Rolling Stone's Jann Wenner that "the Beatles myth" had "just built up, the bigger we got, the more unreality we had to face."

The Beatles, as a band and as a myth, had always emphasized Apollonian sheen over Dionysian honesty. When "Beatle honesty" did emerge, as Roy Carr and Tony Tyler observed in The Beatles: An Illustrated Record (1978), it "veered perilously close to masochism on occasion." Maybe McCartney, like his erstwhile-partner-turned-media-sparring-partner, felt that by approaching the ditch he was facing reality. How Lennon and McCartney each faced the reality of a solo career reflected their divergent personalities. That each man displayed a degree of masochism reflected their shared history--and kinship.

In recording Wild Life spontaneously, McCartney might have been thinking of Dylan's semi-comeback album New Morning (1970) as "real." But if so, he might not have registered that the gentle, joyous New Morning was Dylan's swift response to where demythologizing had landed him: in the stardom-avoidant ditch of Self Portrait (1970), the record he subsequently needed to come back from. "What is this shit?" rock critic Greil Marcus famously asked about Self Portrait. In addition to being a throw-everything-at-the-wall attempt to defy deification, Self Portrait was also a portrait of music-making as a process.

What musician wouldn't want to follow Dylan's lead in revealing his messy working methods, the shitty innards of his art, to the point of having to redeem himself in the public eye as a creative force? The opening of Wild Life might be considered McCartney's one-song steering toward Dylan's pothole, or shithole—call Self Portrait what you will, it then added up to a whole mess of derision and head-scratching, even abandonment by fans. So, "cool, man! Let's go for it!"

Wild Life's first song, "Mumbo," begins with the sound of a tape deck picking up music already in progress. The band is pounding away, with piano and drums prominent. McCartney says, "Take it, Tony," presumably to the engineer since there's no Tony in the band, then scratchily sings, "W-e-e-e-e-l-l-l-l . . ." And then . . . what? Something. Sounds like "I'm on and I'm breaking" or "An arm and I break it" or--your guess is as good as these lyrics. McCartney loves wince-embracing wordplay, and the title "Mumbo" turns out to be a cute way of saying "mumble," as in how you might utter improvised sounds. Under a jazz singer's control, within the context of an actual song, the result is scatting. Here, it's just baffling.

On the song goes for four minutes. McCartney stops singing; the band keeps pounding out its T. Rex stomp; guitars ring, their brightness contrasting with the rhythmic heaviness; McCartney sings more indecipherable syllables; and the groove keeps on until quickly fading out. Since this isn't some lo-fi alternative exercise, you think: "What is this shit?" Yet, because McCartney seemingly can't fight the desire to please, even this mildly glorified rehearsal tape has its charms, such as the backup singers' exuberant "wooo's." It's only rock and roll, but it might prove irresistible if you surrender to its meaninglessness.

Next up is "Bip Bop," whose pleasant country-rock bounces more lightly than the "Mumbo" groove, as if T. Rex were covering "Heart of Gold" or Dylan's "Lay Lady Lay." But somehow McCartney's lyrics "Put your hair in curlers / We're gonna see a band" come across as even less profound than Young's "I been to Hollywood / I been to Redwood" or Dylan's "You can have your cake and eat it too." McCartney's geniality in song can turn even a seemingly meaningful couplet into a marshmallow-filled chocolate egg. Wild Life's one-two punch of seemingly meaningless, bizarrely negligible opening numbers tacitly announces that Wings will be about sound, decidedly not about substance.

Track 3 is a reggaefied cover of Mickey & Sylvia's 1956 R&B hit "Love Is Strange." The band lays the groundwork for over a minute before background vocals start, and even then the singers harmonize on the chorus for another two minutes before McCartney comes in with a typically effortless yet throaty lead vocal. Omitting the original's touch of genius--the "How do you call your loverboy?" exchange between Mickey and Sylvia--this version is neither bad nor necessary. Beatles fans chew over ex-Beatles' choices of songs to cover, and this choice answers the perennial question of what a Caribbean lounge act fronted by an ex-Beatle might sound like.

Side 1 of the original vinyl ends with the make-or-break title track, the band's last chance to win you over before you flip the record over, fling it at the wall, or file it away as not your favorite. After a little acoustic-guitar intro in which McCartney croons that "the word 'wild' applies to / The words 'you' and 'me,'" the band begins a death march. The tempo promises significance. Organ provides a circus ambience. It's a death march at the circus. The skeletal instrumentation grinding away recalls significant paths Lennon had taken: on Abbey Road's "I Want You (She's So Heavy)," on his "Cold Turkey" single, and throughout John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

People speculate that this song and others on Wild Life, Ram, and Band on the Run are salvos in McCartney's public feud with Lennon. Whatever the composer's intent, lines such as "We're breathing a lot / Of political nonsense in the air" and "You better stop / There's animals everywhere" at least give the listener, for the first time on this album, something to ponder beyond the oddness of the creative choices. As when the music on Dylan's Self Portrait is Ramshackle or that on Young's Tonight's the Night is distorted, out of tune, and drug-addled, "Wild Life" isn't conventionally good. It's eerie, harsh, and challenging. McCartney screams the title phrase and others. He dares you to ask why he didn't bother fixing his flub of "aminals" for "animals." Because first takes rule? Because he found it childishly funny? Because he was overindulging in marijuana? In any case, as the side ends, with the background singers repeatedly asking "Whatever happened to / The animals in the zoo," all the nuts and bolts on display are more fascinating than a lot of pop-rock meticulously produced for mass consumption.

Side 2 opens on much more familiar McCartney territory. A lovely song that would have sounded fine on one of the later Beatles albums, "Some People Never Know" combines rich acoustic guitar, bold piano, and loping rhythm section in a way that for some people defines '70s soft-rock. The melody builds toward the chorus ecstatically. The instrumentalists have some room to roam until the whole thing winds down into a funkyish percussion break. The lyrics are innocuous but better than "bip bop bip bop bam."

Also better is "You are my song / I am your singer," the key couplet in the brief, shimmering "I Am Your Singer." Listeners uninclined to give Linda McCartney a break might be put off by her co-lead singing here, but she sounds fine, amateurish but sweet, like the prototype for so many indie-rock warblers. Listeners inclined to give Wings a break might feel that, with at least two pleasant numbers, side 2 of Wild Life justifies patience.

The writer of "Yesterday" now gives us "Tomorrow" ("When we both abandon sorrow"), which of course suffers by comparison but is a fun piece of fluff that could be the Beatles or Badfinger. It was recorded in 1976 by popster David Cassidy, so at least one person in the world was listening appreciatively to Wild Life decades ago, before revisionist fans started singing the album's praises.

If there's a solid reason to revisit this record, it's the final cut, "Dear Friend," which we now know was recorded for Ram but would have changed that album's playful mood considerably. McCartney at the piano, with bass and effects and percussion and horns, ruminates over an open letter that doesn't say much but suggests wounds: "Is this really the borderline? . . . Are you afraid? Or is it true?" If this track were by Neil Young in the ditch--or by Alex Chilton on Big Star's shambolic third album (1974)--we'd feel the pain and honor the effort, celebrating the way the song keeps stopping and starting over, as though the singer just can't keep from dipping into the pool of tears or spilled beer or spilled blood at the bottom of the ditch. Instead of that recognition happening, however, copies of Wild Life that actually sold back in the day were probably never flipped to side 2. As a result, many people really did never know about this fascinating non-silly love/hate song.

It's little wonder, then, that Wings' pilot approached the group's next project unconfidently. Reissues have revealed that Red Rose Speedway almost became a two-record set, beefed up with much more serious material than the ditties that make up the single-disc original album. For whatever reasons, McCartney changed his mind. Then, after the initial release, he reportedly became dissatisfied with the finished product. To keep band members from getting bored during the sessions, he'd given everyone something to do; and in his mind, overdubbing had left the tracks overwrought.

But all these years later, with so much massively layered sound and empty-headed repetition having been produced in the name of pop-rock--much of it inspired by McCartney or by musicians inspired by him--Red Rose Speedway seems elegantly spare, like a model of restraint. If it had been released as two discs, people would call it Wings' "White Album" and wish it had been pared to essentials. McCartney's response to "White Album" detractors is "Shut up," and maybe at this point he'd say the same to Red Rose Speedway naysayers.

The first side starts with "Big Barn Bed," a mid-tempo semi-psychedelic hoedown. Its lyrics begin with a fragment first heard on Ram, "Who's that comin' round that corner? / Who's that comin' round that bend?" and don't grow much more interesting. Production and momentum matter most, as McCartney & Co. exhort you, the listener; you, an unnamed woman; and you, everyone, to "keep on sleepin' in a big barn bed." If Phil Spector had produced a cover of Dylan's "Lay Lady Lay" by Mott the Hoople, it might have reverberated like this.

Next comes "My Love." The rock critic Robert Christgau hated Red Rose Speedway even more than he'd hated Wild Life, to the point of calling Speedway "quite possibly the worst album ever made by a rock and roller of the first rank." Christgau thought the hits collection Wings Greatest (1979) was OK, but "all I could ask [for] is a stylus-width scratch across 'My Love.'" If you're familiar with vinyl, you know the comment makes no sense. He wanted Wings Greatest to become unplayable at the middle of side 2? He wanted to hear clicks all the way through that song if the stylus still tracked? Clearly, though, the love on display from McCartney doesn't generalize in all directions. And in the end, the love you make is not always reciprocated.

"Try a little love / you can't go wrong" is the message of "Get on the Right Thing" and perhaps the message of all McCartney's work. Is he preaching to his haters? "Well, you know they were wrong . . . You knew it all along." Perhaps the solution to people never knowing is to get on the right thing. Delivered by a soul singer, these lines might signify as sociocultural comment, even personal-is-political protest. Because McCartney coats them in sugar, with a smile in his voice and backup singers cheering him and you and everyone on, any sign of trouble is in the rearview mirror, and the result is gravity-free pop.

By contrast, on "One More Kiss" McCartney peers into the Beckettian ditch and howls at the horror of existence. No, not really. If Red Rose Speedway were a musical, the singer of "One More Kiss" might be perched next to his ladylove at a malt shop counter or on a park bench. He apologizes for having hurt her, explains that "I must be on my way," and asks for "one to remember." You'd need a hard heart to hate this little bit of nothing. It'd be like hating a hamster. But for a strong sense of why people tend to fall in either Lennon's camp or McCartney's, compare this song with, say, "Jealous Guy" or "Oh My Love" from Lennon's Imagine (1971). Even when Lennon sounds most like McCartney, you get a hint of melancholy. You can still taste piss and vinegar, or at least imagine you can. With McCartney, you're always risking diabetes. And his feeling, as he later put it in "Silly Love Songs," is "What's wrong with that?" Some people find that attitude infuriating.

"I have no answer for you, little lamb / I can help you out / but I cannot help you in." Side 1 of Red Rose Speedway ends with the collection's strongest stab at substance, "Little Lamb Dragonfly." At a tempo that could be taken as elegiac, amidst strummed acoustic guitars that could be heard as contemplative, the singer offers consolation: "Sometimes you think that life is hard / And this is only one of them / / My heart is breaking for you, little lamb / I can help you out, but we may never meet again." But this touching section turns out to be fleeting, and after a Beatles-like transition of "la, la, la's" the scene shifts, and the singer is now addressing someone or something else:

Dragonfly, fly by my window

You and I still have a way to go

Don't know why you hang around my door

I don't live here anymore

Since you've gone I never know

I go on, but I miss you so

Dragonfly, don't keep me waiting

(I'm waiting--can't you see me--I'm waiting)

When we try, we'll have a way to go

Dragonfly, you've been away too long

How did two rights make a wrong?

Since you've gone, I never know

I go on, but I miss you so

In my heart, I feel the pain

Keeps coming back again

Dragonfly, fly by my window

(I'm flying . . . )

They're not the best lyrics ever written; but as so often happens with McCartney's work, you can't help wondering how listeners would take them in a different context. What if Lennon, Young, Dylan, or Chilton had sung them? What if Kurt Cobain had? Or Billie Holiday? Or Billie Eilish? Would we feel the pain? McCartney welcomes you in--you're always welcome in McCartney's world--but he doesn't expect you to be the singer, the lamb, or the dragonfly. You're there to be entertained, whatever the matter.

Flip the record, and on "Single Pigeon" the singer addresses two more creatures: the title bird and a "single seagull." But he doesn't really address them. He wonders if their solitariness, like his own, reflects relationship trouble: "I'm a lot like you... Did she throw you out? . . . Did she turf you out in the cold morning rain again?" When McCartney's piano gives way to a blast of horns, it's like brilliant sunshine bursting through clouds, but by song's end the singer's dilemma remains unresolved: "Sunday morning fight about Saturday night." Once again, if the track weren't so pleasant, so easy to take in, the pain below the surface would be bursting out, like the remembered pain that for decades kept Young from reissuing Time Fades Away. With "Single Pigeon," take away its composer's facility with melody and his crafting of tasty textures that trigger pop-rock synaesthesia, and you'd be left with a more complicated emotional palette than the surface suggests. Fiona Apple could rip the bloody heart out of this one.

Of course, throughout his career McCartney has proven constitutionally unwilling or unable to stay complicated or emotional for long. Here he follows the melancholy of "Single Pigeon" with a return to the malt shop in "When the Night." Forgive him for creating this variation on Abbey Road's "Oh Darling!" but ponder why that song carried some weight while this one floats along in a bubble. McCartney's committed vocals unite the two songs and are their greatest strength. In delivering each song's melody and disrupting it with swoops and growls, McCartney indicates that the situation matters. If the bubble is in any danger of being punctured, if there's any tension in this little love story, it resides in the man's voice.

He chooses not to employ that asset in the next track, "Loup (1st Indian on the Moon)," an instrumental that even Red Rose Speedway partisans have trouble defending. The vaguely tribal drumming recalls "Kreen-Akrore," the all-but-unlistenable riffing-and-drumming workout that concludes McCartney. Instead of that number's heavy breathing (literally), "Loup" gives us Wings' faux-native-American chanting, plus some Pink Floydish sound effects. Listeners inclined to think kindly of this album's second side may find their good will tested. Those aware that, in pruning the album from two LP's to one, McCartney included "Loup" instead of many worthier alternatives may once again ask themselves--this really comes in handy when craft meets crap--"What is this shit?" I don't mind "Loup" as something different and heartfelt, but I'm listening to a copy of Red Rose Speedway that I bought at a thrift shop for a dollar after having sold my first copy about 35 years ago, so for me, the stakes are low.

I didn't sell Wild Life at that time, by the way. In fact, I still have my original. I remember thinking, "This album is so weird, and you're never going to hear it on the radio. Keep it!"

When I hesitated about selling Red Rose Speedway, it was because of the 11-minute final track, "Medley: Hold Me Tight/Lazy Dynamite/Hands of Love/Power Cut." Why this sometimes clunky assemblage was designated a medley whereas the two parts of "Little Lamb Dragonfly" weren't is one of those mysteries that may be explained only by marijuana overindulgence, but the deliciousness of these pop nuggets renders reasons and reason beside the point. Either you sink your teeth into the chocolate and lose yourself in the marshmallow, either you like the way your teeth hurt through the combination of thickness and lightness, either you take deep pleasure in the way Linda echoes the word "miracle" a few times after Paul sings it, either you look forward to hearing all the melodic fragments repeated instrumentally at the end, either you ask yourself how McCartney concocted a suite so winningly McCartneyesque, or you ask yourself how a once-bright star in the rock and roll firmament could have fallen so far . . . and plopped into a sea of twee.

An obvious comparison with this medley is the classic one that, despite Lennon's distaste for the idea, concludes Abbey Road. Is one of these McCartney-stirred cocktails necessarily more worthy of money and time, more valuable, more entertaining, more artistic, more anything than the other? By the same token, is McCartney's repetition of the phrase "hold me tight" less artistic than Young's repetition of "tonight's the night"? If so, why so? Just because the one's about love and the other's about death? If you can explain the differences to me, objectively, verifiably, in terms of aesthetic appreciation and not personal taste, I'm all ears.