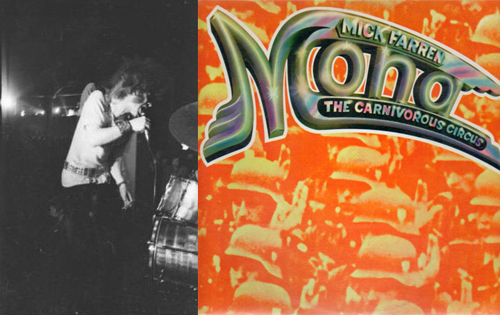

MICK FARREN AND THE CARNIVOROUS CIRCUS

An exploration of Mona

by Dr Elwood Mole

(December 2012)

"There is no place else to go

The theater is closed

Cut word lines

Cut music lines

Smash the control images

Smash the control machine."

- William S. Burroughs

Mick Farren's 1970 solo album Mona the Carnivorous Circus sounds like a deranged monster movie suite. An extended, heavy psychedelic jam with Wagnerian overtones or as its own author describes it, "a personal audio twilight of the gods." Recorded after Farren's dismissal from his band The Deviants, during the transition to a convulsed new decade, the album is empowered by a raw, despaired sense of sonic turbulence and epic magnitude; and in retrospective, it might well be the best Deviants album without the Deviants. A more muscular and matured sequel to the band's brilliant 1967 debut album Ptoof!.

While in Ptoof!, Farren had still managed to retain some creative control over the finished product, while the band's subsequent releases (Disposable and Three) were weaker attempts at polishing their sound into something more conventional to the spirit of the age. After getting the boot from the band, Farren was left unsupervised at the controls, and the result was a powerful and intense piece of work.

Mona unfolds through a series of long electric grooves interspersed by voice cut-ups, interviews with a Hells Angel and Steve Took (of T. Rex), plus snippets of found sound. The record features two main themes, "Carnivorous Circus Part I and II," which is "intercut with a dubbed version of Hitler's speeches, backward tam-tams, Sabre jets in a power dive, a recurrent serial-murderer character, a chant of "who needs the egg?" and a gratuitous Eddie Cochran song" - all culminating in a 7 minute anarchic version of Bo Diddley's "Mona," enriched by wild percussion and juxtaposed Bartok-like descending cello lines in a joyful celebration of the primal heartbeat of rock 'n' roll.

Reflecting his anger and frustration towards his deserting band mates and the rapidly disintegrating youth movement in which he had taken an active role in (as editor and writer in International Times (IT) and later co-founder of the British version of the White Panthers Party), Mona rummages through a whole "When The Music's Over"-like dark landscape of enraged disappointment, mixed in with some of the same brand of fried-brain abandonment that permeates Kim Fowley's demented opus Outrageous - the only difference being that while Fowley didn't take drugs (according to himself, he didn't need to), Farren recorded his solo album in the aftermath of a heavy psychedelic meltdown.

Mona was also an ambitious artistic endeavor, as Farren proposed to deconstruct the whole idea of a rock & roll album by attempting to do the musical equivalent to William Burroughs' literary cut-up technique. How did he seek to achieve this? "Well," says Farren, "there's obvious stuff like cut-ups and random overlays, plus ultra-drug culture poetry, but I was also trying to replicate the nightsounds of Interzone. Which I hear in my head too much of the time." With Ptoof!, there was already a lot of sonic cut-and-paste, courtesy of engineer Jack Henry Moore, a sound collagist who had studied with John Cage and had introduced the band to such innovative techniques as running tape loops between two recorders and taking bits of found-sound from TV and radio. Mona takes these experiments a step further, out of early-Mothers of Invention terrain and into murky, uncharted territories.

"Uncle Bill (Burroughs) was the counterbalance to peace and love fa la," Farren adds. "He was the Queer Agent of the insect trust (another Burroughs reference and later another band's name), making sure the hippies remembered what could happen when the sun went down and the invisible men came out." By 1970, the sun was setting rapidly and the invisible men were out in the open, working relentlessly around the clock to restore the world into normality.

For further details about this sonic extravaganza and his other related work, I further interrogated the source himself.

PSF: Do you agree with Marilyn Manson's statement during the Bush era about "art being at its best when you're underneath a more repressive regime"?

MF: Yes, absolutely. Just as one fights a hell of a lot harder when you're outnumbered with your back to the wall. At times though, one does tend complain "who the fuck needs all this strife?"

PSF: How did you get the opportunity to make a solo album with complete artistic freedom?

MF: Make a deal. Promise the businessmen anything. Then go to work in a way that no one except the engineer and the musicians (who will go along with your shit, if only out of morbid curiosity) has a clue what you're doing until the thing's mixed and it's too late to do anything about it. If the record company suits show up at the studio, immediately stop work and take them to the bar (and make them pay).

PSF: You say in your autobiography that "Mona was, in almost every respect, the product of a desperate need for vindication." So, in a way, Mona's a bit like your Trout Mask Replica, in the sense that you had complete artistic freedom with a vengeance. What's your thoughts on the good Captain and did he have an influence in the music you were making?

MF: Let's put it this way. Both the Cap and I were influenced by the mighty Howlin' Wolf. We both share a sense of galactic absurdity. On the other hand, I have never really worked with cats like the Magic Band (as crazy, but different) and our psychoses are very different. We are definitely in the same line of work though.

PSF: There are many references to the Hell's Angels in your work, including an interview with one in 'Mona.' What interested you about them?

MF: I liked their powerful vanity that they could see themselves as a warrior caste in the middle of the 20th century. They also put the fear on the squares and that's always amusing.

PSF: What did the other members of the Deviants think about Mona?

MF: It was exactly what they expected and that's why they weren't playing on it.

PSF: Who needs the egg?

MF: 147 schizophrenics currently in hiding.

PSF: After recording the album, you relate in your book that you suffered some kind of mental and physical breakdown. Was this exhaustion the result of "meddling with the primal forces of nature"?

MF: The primal forces of nature are a piece of cake. Trying being shut in a broken-down ragged Ford with the rest of the Deviants and too much crank and alcohol for three years, and then get busted out of that to directly make an album. That'll fray a poor boy around a few of his edges.

THE DEVIANTS

"Stand back, all! Something takes shape within the swirling mist!!"

back cover of Ptoof!

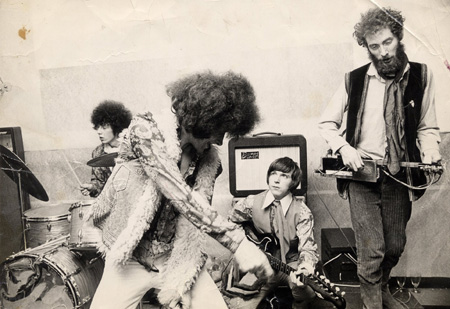

According to Farren, the Deviants original aim was to "make it as a loud, basic rock band" playing "British amphetamine psychosis music." They were no more than average musicians- instead their most distinctive appeal lay on a sneering, aggressive attitude (that pretty much predated the punk scene) in the midst of flower power. They represented the angry second league of British psychedelia, pointing their finger at the naive lightheadedness of the hippie movement and its rapid commercialization. "Everywhere one looked, money was being generated," Farren complains, "even before it was fully formed, the philosophy had become a fad."

Considered the first record to emerge out of the English underground, Ptoof! was a totally independent production - manufactured and distributed by a DIY "crew of hired hippies." Finances were provided by a recent acquaintance of the band, an alcoholic rich kid who had inherited a fortune after his millionaire father committed suicide (Farren reports that he would later finance an abortive Marxist revolution on the island of Trinidad, which prompted his shocked family to commit him to a psychiatric institution).

With an iconic Roy Linchenstein-like cartoon explosion on the cover, Ptoof! was a deranged musical brew of 60s R&B, proto-punk and musique concrete - like a punkish take on Zappa's Freak Out as played by a group of (more) musically-inept freaks. The album opens with "I'm Coming Home," a mean, shuffled blues that culminates in sheer sonic mayhem, somewhere near the Velvet's "Sister Ray" (story goes that they had stolen their demo from producer Joe Boyd, long before anybody had heard about them). The two center pieces of the album, "Garbage" and "Deviation Street" are brilliant Zappaesque collages, with a tone as defiant and scornful as anything the Sex Pistols would do a decade later.

"just like Jimi Hendrix..."

"it's a stone groove..."

"he's simulating the acid experience, maaan"

Originally, the record featured two songs, "Child of the Sky" and "Bun," which seemed completely out of place within the album's subterranean dementia. These were sweet, melodic '60's songs written and performed by a temporary band member named Cord Rees. Farren explains that the inclusion of those tracks were done as a compromise with Rees. The songs were discarded in a later reissue of Ptoof!.

DEATH OF A DREAM MACHINE

"Everybody's got something that they've just got to prove"

- Deviants, "Fire in the City"

The Deviant's next release, Disposable, was an half-assed effort to take the band a step further into something closer to a more "conventional" late '60's sound. The album was done in a straight series of amphetamine-fueled sleepless hours and the final product was somewhat unbalanced, lacking the energy and creativity of its predecessor. Yet the record manages to deliver a few interesting moments, among them the conspiracist psychedelia of "Jamie's Song," the defiant "Slum Lord" (with a disappointingly lame tape-slowing-down ending) and "Somewhere to Go," which even though it basically repeats the structure of the previous album's opening song, still manages to stand, in contrast to the rest of the material in Disposable, as a finished and coherent piece.

Farren refers to their third album (The Deviants 3) as the record that they should never had made. Once again, the final product was an uneven effort to take their music further into rock & roll conventionality. But even though it's pretty far away from the maniacal collages of their debut, Deviants 3 somehow manages to be a much more consistent collection of songs than Disposable. Musically, it tends to be more focused and you can hear that the playing is more solid, which can be good at times, but it also means that the musicians occasionally slip into bland '60's electric blues formalities.

But still there are some cuts who can be saved from the general mess, namely the opening killer track "Billy the Monster," the instrumental "Broken Biscuits," "First Line (Seven The Row)" which sounds like an out-of-place attempt at capturing the West Coast sunshine sound, the brief Zappaesque jingle of "The People Suite" and the speedy Kinks rip-off "Death of a Dream Machine."

The last track, "Metamorphosis Exploration," is a 'ship-a-going down' blues dirge that reflects both the spirit of the time and the impending feeling of doom among the band. The song features a line that ultimately resumes the general bummer of 1969: "Someone told me times are changing, but looking all around it seems the same."

According to Farren, the Deviants didn't want to be "underground clowns" anymore. Instead they "wanted to become Led Zeppelin." After three albums, they began their first North American tour, which would be interrupted by the mental demise of their lead singer in Canada. The rest of the group would go on to form the Pink Fairies, and Farren was left, dazed and confused, in the devious bowels of Canada's Chemical Row, "one notorious street behind a hippie strip of bars, headshops, poster shops and wholefood emporia," where he found a shady bar he could recoil into.

DOWN CHEMICAL ROW, 1969

foggy notions and faint recollections

Mick Farren shook his head, trying to clear it. Had he been mauled? Mindfucked? Struck by lightning? Large parts of his consciousness were wastelands of fractured shards, data retrieval had become history... He sincerely hoped the apparent garbaging of his memory was purely temporary. Painful as it might prove, it was his and he wanted it back. He was fairly optimistic that it would one day return.

Perhaps he shouldn't have accepted that orange tab of sunshine acid.

He got up, walked through the urine smelling corridor and into a squat toilet with walls of blue glass and underwater shots of spermy soap in neon fingers. The lights were buzzing intricate patterns and vibrant shapes sounding like a chorus of a thousand miniature cellos humming in a continuous high-pitched drone. He avoided looking at his face in the mirror and returned to the seat in the dim motorcycle bar that had been nurturing his intoxicated mind for the past few days. Or had it been just a few hours? It didn't really matter anymore.

He was now hallucinating to the point of near blindness. The only thing he could make out in the dim atmosphere of the bar was the unmistakable vacancy in the eyes of a high percentage of the revelers. They too had sacrificed mind and memory to the specific moment.

The street door opened abruptly and a shadowy figure walked out of the bright pale light which momentarily reminded him of a whole alien day-world outside the warm dark red microcosm of the bar. The background music faded out and a familiar dead radio voice was heard through the speakers:

"His time was running out its last black grains. Shaking his head and pushing the air a vulture will into his brief case. He walked out and got light pink instructions terminal Chinese commuters. there is the work of getting it off the shelves and that is what we do. We are not interested in the individual models, but in the mold, the human die. This must be broken."

For a moment he felt dizzy and disoriented, as though mind hadn't quite locked into body and the two were operating out of phase. With an effort of concentration, he eased the two halves of himself together until he felt as though they were properly meshed, then he waited a moment and the dizziness passed. It took him a seemingly long, although obviously immeasurable time to realize how the way out was in fact ridiculously simple and completely in his own hands.

Farren returned to London, re-grouped and began making preparations for his debut solo album.

THE WHOLE THING STARTS

"As the storm clouds gather, my songs become documentaries and the sounds become harsh and strident. I would like to think the clouds are only in my head, but too much proves otherwise."

- advertisement for Mona in International Times

Back in the UK, faced with the contractual obligations to record a fourth Deviants album, Farren assembled a sort of demented, post-psychedelic all-stars group comprised of ex-Tyrannosaurus Rex percussionist Steve "Peregrine" Took, ex-Pretty Things drummer and vocalist Twink, John Gustavson and Pete Robinson of British prog band Quatermass, American guitarist Steve Hammond and cellist Paul Buckmaster (who also played in Miles Davis' On The Corner, did the orchestral arrangements for Bowie's Space Oddity and would later compose the score to Terry Gilliam's 12 Monkeys movie).

In December 1969, they went into Sound Techniques studio in London where Mona was recorded and edited. Farren admits that he was "crazy" while doing Mona- "(I was) really mentally ill. If I listen to it, I can still feel it. Maybe I should have chilled out for a few months before making the album." He remembers that after listening to the record, people began to look at him 'very strangely.' Nevertheless, Mona was Farren's last chance to flex his experimental muscle, something that had been denied since Ptoof! by the other members of the Deviants, who unanimously pushed the band in a more guitar-oriented musical direction.

Out of the contextual frame of the era, Mona survives as both a unique piece of artistic authenticity and a genuine testament to the period it was recorded in. It's a personal statement which manages to reflect that particular era of transformation that was the end of the '60's and the beginning of the '70's.

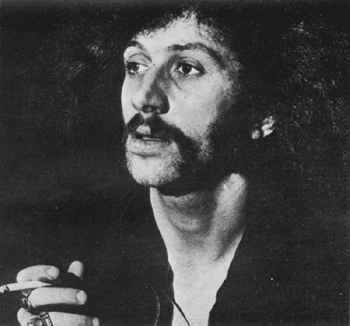

"I remember staring at the microphone like it was a live cobra. Paralysed by fear, the monkey was unable to perform, but pretty soon I ceased to be a primate or even mammalian. I was down with limbic reptile. I opened my scaly phaser ports and fired at will."- Mick Farren, Give the Anarchist a Cigarette

NOTE: The section titled 'DOWN CHEMICAL ROW, 1969' contains some paragraphs extracted from Mick Farren's novel Jim Morrison's Adventures in the Afterlife (with the name "Jim Morrison" replaced with "Mick Farren") and some bits taken from WIlliam Burroughs' The Soft Machine.

Apart from an email interview with Farren, all his other quotes were taken from his autobiography Give The Anarchist A Cigarette.