The Taurus in Winter: Mingus in the 1970's

Photo by Lee Friedlander: Lee's work can be found at Janet Borden Galleries

By Tim Ryan

(October 1999)

At the dawn of the 1970's, Charles Mingus, the greatest bassist who ever

lived, was ready for a comeback. He had not recorded since 1965. Evicted from

his apartment with much fanfare (recorded in a film simply titled MINGUS),

prone to drinking, occasionally arrested for vagrancy, the late 1960s were a

dark, nearly silent period for one of the most outspoken and intense

personalities in the pantheon of jazz. Though he occasionally performed music, Mingus devoted himself to photography and to completing his autobiography, BENEATH THE UNDERDOG. It was finally published in 1971, giving the world a taste of the brilliance and flights of fancy that existed in Mingus' brain. Much of the book, amazing as it is, was fiction, and the main character is not Mingus himself but an angel watching over him. Regardless, the brilliant first line ("In other words, I am three") described the multifaceted genius' contradictory state of mind, and indirectly set the tone for his recordings in the final decade of his life. Mingus in the 1970's was indeed three was three: a keeper of the jazz tradition, a continually restless innovator, and, above all, a legend finally getting his due. After writing perhaps the greatest book ever by a musician, it was time for the restless Taurus to return to music.

Mingus' first release after his retirement, Charles Mingus With Orchestra (Denon), isn't quite a return to form, but it's a good beginning. Performed with a competent orchestra in Japan, Mingus (with Bobby Jones on sax, Eddie Preston on trumpet, and Masahiko Sato on piano) sounds great; his solos are supple and fluid, and if the arrangements aren't totally earthshaking, With the orchestra taking it easy for much of "The Man Who Never Sleeps," Preston and Mingus play a spacious, pretty duet. It's not a masterpiece, but With Orchestra is very nice.

It took Mingus next to no time to regain the astonishing gifts that made him the greatest jazz composer since Duke Ellington. Let My Children Hear Music (Columbia) is on par with The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady (Impulse!) and Mingus Ah-Um (Columbia) as one of the finest records of his career. "Adagio Ma Non Troppo," an orchestral reworking of the piano tune "Myself When I Am Real," may be the finest of Mingus' forays into his own "Jazzical" music. "Don't Be Afraid, The Clown's Afraid Too" shows that Mingus has a potent circus-as-metaphor-for-life streak a la Fellini. "Hobo Ho" is the equivalent of a big band ambush; sudden bursts of ensemble playing come and go as quickly- and devastatingly- as a hurricane. Oh, and "The I of Hurricane Sue" is also killer. "The Chill of Death" finds Mingus reading a poem he had written more than thirty years before in a voice that sounds like a message from the netherworld. It makes fellow crypt-voice Leonard Cohen sound like he joined the Backstreet Boys (if you don't believe me, check out his reading of "The Chill of Death" on the Hal Willner Mingus tribute Weird Nightmare). Though little of the material is new (much of it was performed at a concert at UCLA in 1965; "The Chill Of Death" was written in the 1930s), Mingus had clearly found what he had lost, and the result was some of the most powerful, moving, and finally, fun music of his great career. And it signified that a new chapter was about to be written.

Mingus had re-emerged with his skills completely intact, so the next thing to do was obviously a return to the stage, preferably with a big orchestra. Charles Mingus and Friends in Concert (Columbia) is the document of a sold-out show featuring many of the tunes from Let My Children Hear Music, as well as some new material and a few standards, featuring everyone from Bill Cosby to Dizzy Gillespie to Gerry Mulligan to Gene Ammons. Some of the new stuff is phenomenal, including the symphonic "Little Royal Suite" and the slow, growling "Mingus Blues." "Jump Monk" also gets a terrific revival, bristling with the same spontaneous energy of the tune's debut at the Bohemia in 1955. However, most of the tunes are overlong, overdone, and overblown; it's nice that everyone tried so hard, but there's not much that really grabs a listener. Columbia's double-disc reissue of the show doesn't help matters. Particularly disappointing moments include Honey Gordon singing "Strollin'," a version of "Nostalgia in Times Square" that doesn't benefit from a reworking, and "E's Flat, Ah's Flat Too," which just doesn't rock the way it's supposed to. However, regardless of the results, Mingus was officially back, and it's nice to hear the warmth of Bill Cosby's between-song monologues. He sounds as happy as the audience must have been to see Mingus back on the scene.

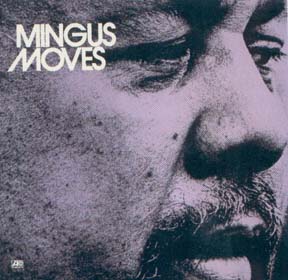

Whether or not he was hoping to attract the mainstream audience that had

often eluded him during periods of great creativity is debatable, but Mingus

plays it pretty safe on Mingus Moves (Atlantic). The album has some good

stuff on it, particularly "Canon," the eerie opener. Honey Gordon redeems

herself on "Moves," and "Opus 3" gets really cool as it goes along. But

"Canon" sounds a lot like John Coltrane (whose compositional style Mingus

never loved), "Flowers For a Lady" sounds like cocktail music, and "Opus 3"

closes the record just as things start to get interesting. The record is

well-crafted and glossy, making for a pleasant listen while disguising some

of the more edgy moments.

Whether or not he was hoping to attract the mainstream audience that had

often eluded him during periods of great creativity is debatable, but Mingus

plays it pretty safe on Mingus Moves (Atlantic). The album has some good

stuff on it, particularly "Canon," the eerie opener. Honey Gordon redeems

herself on "Moves," and "Opus 3" gets really cool as it goes along. But

"Canon" sounds a lot like John Coltrane (whose compositional style Mingus

never loved), "Flowers For a Lady" sounds like cocktail music, and "Opus 3"

closes the record just as things start to get interesting. The record is

well-crafted and glossy, making for a pleasant listen while disguising some

of the more edgy moments.

Apparently realizing he needed to get back to basics, Mingus tried his hand at yet another all-star live album. Mingus At Carnegie Hall (Atlantic) features an all-Ellington set list. As it is, "Perdido" and "C Jam Blues" don't sound terribly dissimilar in the hands of the Mingus group. But what may look like a nostalgia session is anything but, what with Rasaahn Roland Kirk giving his usual spazz/ purist soloing and Jon Faddis also playing well. It's not Mingus' most electrifying album, but it's still fun. (A bootleg of a performance from a few years before, Parkeriana [Bandstand], features a fine live Ellington medley performed with a quartet.)

Duke Ellington died in 1974, leaving a great void in the jazz world. With Louis Armstrong gone a few years before, and Miles Davis no longer the toast of jazz purists, Mingus began to inch his way into the role of elder statesman. Not that that stopped his ambition; Mingus beat Guns ‘n' Roses to the punch by 17 years by releasing two albums simultaneously. Changes One and Changes Two (Atlantic) were recorded at the same time with a solid combo (George Adams on tenor, Jack Walrath on trumpet, Don Pullen on piano, and Dannie Richmond back behind the kit), and both feature a version of "Duke Ellington's Sound of Love," One instrumental and Two with vocals. Changes One is OK, but never really catches fire; "Sue's Changes" is very nice, but on "Devil Blues," Mingus' overdone singing (though it's competent) isn't nearly as cool as his off the wall blues on Oh Yeah (Atlantic, 1961). Changes Two, however, is a real revelation. Making the absolute most of Don Pullen's free piano solos, Mingus and the band plunge into a sonic whirlwind on "Black Bats and Poles" and "Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blue." The echoey production, which sounded glossy on earlier records, creates an eerie, post-Watergate tension. "For Harry Carney" (a tribute to the recently deceased Ellington sideman) ends the record on a meditative note. Mingus' bass solo, high- pitched and lyrical, is as mournful as anything in his canon except "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat."

Mingus spent the next few years touring before returning to the studio to record his weakest album, Three Or Four Shades of Blues (Atlantic). The lame fusion attempt has all the earmarkings of an album from which Mingus was relieved of control (indeed, Mingus was not pleased the first time he heard the album). Including fusion guitarists Larry Coryell, John Scofield and Philip Catherine may have been an attempt by the producers to make Mingus "relevant" to a new audience. What's most depressing about the record is that Mingus and band turn in solid performances in spite of the boring, endless solos turned in by the ax-men. Hearing the fusion style guitar solo on the opening of "Better Git Hit in Your Soul" after Mingus' opening bassline is like having a Little Leaguer behind Hank Aaron in the batting order; the contrast is embarrassing.

Finding his muse one last time, Cumbia and Jazz Fusion (Atlantic) is one of Mingus' greatest works, second only to Let My Children Hear Music as his best album of the decade. Miles Davis once remarked that Mingus and Ornette Coleman needed to listen to Motown, and it seems both responded to the subtle challenge at the same time; Coleman released the R&B heavy Dancing In Your Head (A&M), and Mingus' basslines on Cumbia are the closest to funk as anything he'd ever try. The title track expands on the melody of "Los Mariachis" from New Tijuana Moods (Bluebird, 1957). Rather than being the tourist he was in Tijuana (no matter how perceptive), however, Mingus and orchestra sound totally at home in the proto-Worldbeat of "Cumbia." The driving percussion, and "Music For ‘Todo Modo,'" the haunting, expansive piece that rounds out the album, keeps the surprises coming, with a great organ solo and a swinging arrangement between, slow, semi- free improvisation. The CD version of the album rounds out those fine pieces with two sweet solo piano takes on Mendelssohn's "Wedding March," and it's everything all great Mingus songs are: powerful, human, inspired no matter how familiar, with every note a telegraph from a great man's soul.

After such an achievement, Final Work (CMA Jazz) is especially disappointing. An all-star cast comes together to record absolutely flat versions of some of the rockingest jazz tunes ever. Whereas the 1963 classic Mingus, Mingus, Mingus, Mingus, Mingus (Impulse!) revisited various songs in Mingus' catalogue because Mingus had found something new to say about them, Final Work could be the work of anyone; there is little on the record that gives much indication of Mingus' compositional style, and ability to write arrangements that allowed for startling creativity by the soloists. Mingus remade and reinvented his own songs so frequently and so well that hearing a by-the-numbers record is really depressing. Mingus' ability to play the bass must have declined appreciably, since he has very few solos. The record is competently played (with guests Lionel Hampton and Gerry Mulligan), but listen to the version of "So Long Eric" on Town Hall Concert (OJC); sparks practically fly off every note. Here it sounds too safe. Paying tribute to Mingus should mean pushing the boundaries, not smoothing out the rough edges.

Mingus was never to be recorded on bass again. Lou Gehrig's disease had severely limited his movement, confining the great, powerful genius to a wheelchair. Several albums (Me, Myself An Eye, Something Like a Bird, both Atlantic) were released featuring his compositions, but with no instrumental input. Trapped inside a body with increasing limitations, Mingus nevertheless had one final triumph. Mingus and other jazz greats were invited to the White House by Jimmy Carter, who, acknowledging his contributions to the lexicon of American music, gave the ailing giant a hug. Mingus wept.

He died in Mexico in the first week of 1979. His ashes were scattered in the Ganges River in India. The underdog left this world in victory.

The final recorded performance of Mingus was a brief, but spiritually overwhelming, vocal duet with Joni Mitchell, "I's A Muggin.'" Initially, Mingus' choice of a folkie like Mitchell to be his final collaborator seems incredibly bizarre. And Joni Mitchell's resulting album, Mingus (Asylum), won't exactly dispel that notion. This is a skeletal album, a good try that never totally works. However, Mitchell does a great job with what she had; sketches of tunes by Mingus to which she added lyrics. The album works best when Mitchell rides the groove, tapping an essence that captures Mingus' spirit (if not his sound). "A Chair in the Sky" does the job the best. Joni's reworking of "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" is great, too; what was once a tribute to Lester Young becomes a eulogy to both Lester and Mingus. However solid these moments are, bassist Jaco Pastorius' space age basslines undercut the best moments. To be fair, it would be nearly impossible to re-enact Mingus' bass style on the album, but Pastorius' noodling ruins the spirit. Mingus wasn't a cold virtuoso; he soloed when he had something to say. Jaco solos all the time, as if to simply prove he can play. Despite Joni's best efforts, it is her sideman who paves paradise and puts up a parking lot.

Mingus passage into the next world hasn't stopped interest in the man's work and life. Various posthumous tributes have been released. Weird Nightmare: Meditations on Mingus (Columbia) gets everyone from Elvis Costello to Chuck D to Henry Threadgill to Leonard Cohen to Keith Richards under the same roof to add their own perspectives on the Mingus legacy, and the album is an absolute gas. Highlight: Chuck D's rap from unpublished sections of BENEATH THE UNDERDOG with Bill Frisell's totally rocking guitar workout on "Gunslinging Bird." More in the purist vein is the Mingus Big Band, operated by Mingus' widow, Sue. Practitioners of a fairly killer live show, it's the closest to Mingus that contemporary audiences may get.

In the last decade of his life, Charles Mingus produced uneven music, occasionally came up with a masterpiece, and finally gained the recognition he had long deserved. Though he wrote in "The Chill Of Death" that "long before death had called me, my end was planned- planned but well," but no one could possibly have made up a story like Mingus'. It's too complex, too contradictory, too alive, to be the work of fiction. Perhaps that's why, 20 years after his death, Mingus continues to captivate.