NINE INCH NAILS

Charlie Clouser interview

by Peter Crigler

(August 2021)

Nine Inch Nails was one of the biggest bands of the '90's. Trent Reznor's take-no-prisoners attitude singlehandedly won over a whole generation with hardly any effort. The music spoke to people who felt disillusioned and alienated. The band was a revolving door of fantastic musicians, but the 1995-2002 lineup was the steadiest and heaviest. Included in that lineup was keyboardist Charlie Clouser. From playing in one of the most insanely popular bands of the '90's to becoming one of the most renowned soundtrack composers of the 21st century, it's been quite the ride for Clouser.

PSF: What got you interested in playing music?

CC: Both my parents were always listening to music in our home, and my mother played piano, but it was always stuff like Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and other prewar music. As a child I took lessons on clarinet, piano, and guitar before discovering the drums, and I played in all the school bands and had a band with some friends in high school. So, music was always a part of my life from the beginning, even though I didn't discover rock music until about age 10 or 11. In college I studied electronic music and recording engineering, but this was before MIDI, before computers, and all of that. In those days electronic music was done with a modular synthesizer and tape loops, and recording engineering meant calibrating the equipment and soldering. But all of that was good experience to have under my belt as the technology changed.

PSF: What were you doing pre-NIN?

CC: By the time I found my way into the NIN camp I was in my late twenties, and I had already been in multiple bands, had record and publishing contracts, made albums, worked as a synth programmer with a TV composer for a few years, and been a "session guy" doing drum and synth programming in New York and Los Angeles. So, I'd been around the block a few times but hadn't really found a situation that felt like home, so I kept bouncing from thing to thing looking for the right fit.

PSF: How did you come to join the band, and what was the initial experience like?

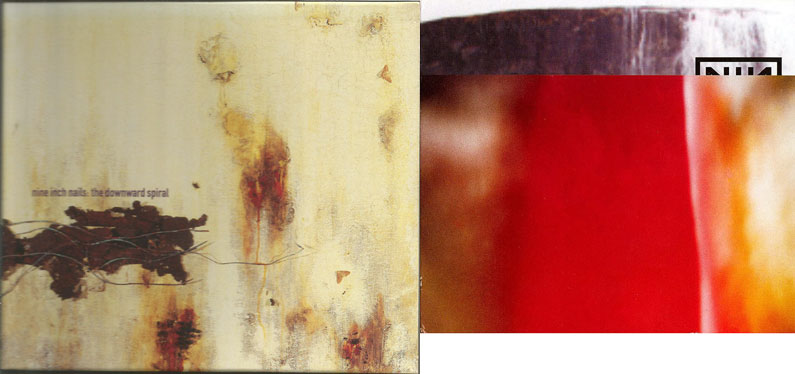

CC: In the early '90s I was in Los Angeles, doing drum programming and electro-industrial remixes for the band Prong, and an old college friend was one of the producers on the NIN video for "Happiness in Slavery," and they needed to do some sound effects for the robotic torture chair that devours Bob Flanagan in the video. Instead of booking time in a conventional audio-sweetening facility, he suggested that they bring me in to Trent's studio to do the effects there, since he knew I had the right sensibility and a large collection of sound effects. So, I went up to the Sharon Tate house with some hard drives full of samples of things like dentist's drills and jackhammers, and we just knocked it out on Trent's rig. We had allocated two or three days to do the work but finished in an afternoon, and at the end of it Trent asked if I wanted to do drum replacement and sample augmentation work on Marilyn Manson's first album, which they'd just finished basic tracking for, but they were unhappy with the sound of the live drums. So, I started right in on that project, and I just sort of never left, eventually helping them finish up the Downward Spiral album and edit and sequence the final masters. It was great to finally be involved with some projects that felt like a good fit with my musical style, and be around a bunch of really talented people who were at the top of their game, and the setup that Trent had up at the house was really top-shelf all the way, so I definitely wanted to stick around.

PSF: What was your experience on the Self-Destruct tour like?

CC: For the first leg of the Self-Destruct tour I was tasked with setting up a portable studio rig so that we could do some work on days off on the tour, and that's how we did the songs and soundtrack album assembly for Natural Born Killers and some other bits and pieces, and eventually I was tapped to replace James Woolley on keyboards in the band. I had to inform Trent that I was actually a drummer and that I'd never played keyboards in front of people before, but that didn't seem to matter that much, so my first time performing on keyboards was in front of about 20,000 people! The Self-Destruct tour was my favorite of all the ones I was involved in because it was just so unhinged and violent, with keyboards being smashed and guitars being thrown into drum kits and all that good stuff, and our openers were Marilyn Manson and The Jim Rose Circus Sideshow, which in my opinion is the perfect triple-bill. The way that Trent arranged the set list was just perfect, with the songs getting more and more violent and destructive until we'd just destroy everything on stage during "Happiness in Slavery," and then the curtain would come down for the quiet section with the front-projected movie section. I loved it, and so did the audience. It really sounded and looked very different from everything else out there. It was great to be involved with such a well-crafted show, at a spare-no-expense level, with the personnel and resources pull it off, and we all had the energy level needed to keep up that level of insanity night after night--and the backstage antics were equally insane to what happened on stage, so that was a nice perk as well.

PSF: How was it touring with Bowie?

CC: By the time David Bowie suggested a co-headlining tour, we had been off the road for a minute and had moved to New Orleans and gotten Trent's studio built out, so we were getting back into album mode and were no longer in the full-destruction touring mindset. This was the perfect opportunity to adapt some of the existing material to a slightly less insane setting, and the best part was the way Trent and David crafted the changeover between bands. Instead of NIN playing a set, then an intermission, then David's set, they created a five-song overlap section where we'd play a NIN song and David would sing with us, then we'd play a Bowie song and some of David's band would join us, then another NIN song with more of David's band appearing, until we played David's "Scary Monsters" with all of the members of both bands on stage--three drummers and four guitarists. It was nuts! Over the course of the next two songs the NIN members would gradually depart, finishing up with Trent singing "Hurt" with David, accompanied only by the members of David's band. That was a genius idea, and it was a dream come true to be on stage with David, who all of us absolutely idolized, and also to have Carlos Alomar jumping up on my drum riser to solo. It was not so much fun trying to keep up with Carlos in a tequila-drinking contest, which no mortal man can win, but we tried anyway. In general, that tour was a bit more calm than the previous outings, both onstage and off, but that's a good thing because I can actually remember more of it! David was a supremely kind, generous, and brilliant man, everything you'd expect and more, and the fact that he even knew about NIN, much less suggested that we tour together, was about the highest compliment we'd ever received. He always had an interesting book to suggest, or an art exhibit to recommend, and at the end of the tour he presented each band member with portraits that he'd painted of us. That portrait is the best and most thoughtful gift I've ever received. David was an artiste through and through, a singularity--we'll never see his equal again.

PSF: Tell me about the production on The Fragile. Was it arduous? What do you think you brought to it?

CC: The production cycle for The Fragile was very long and drawn-out, and we had more than a few side tracks and dusty trails to explore along the way. A testament to Trent's genius is that we sort of assumed it would be The Downward Spiral part II, but he explicitly wanted to go in another direction. So, along the way we fooled around with different influences and directions. We had Tony Thompson come down to New Orleans and lay down drum tracks, we recorded Bill Rieflin playing drums at Steve Albini's studio in Chicago, we took some song sketches to Los Angeles and worked with Dr. Dre for a few weeks--we really went in any direction that we thought might be interesting. Our influences, the music we were listening to at the time, included Photek, Squarepusher, Atari Teenage Riot, Aphex Twin, Autechre, and Ice Cube . . . just a really wide range of stuff we thought was interesting. There was a period of almost two years that we spent just recording sketches and trying out ideas, most of which never saw the light of day, but all of which were stepping stones to our eventual goal. The final destination can't really emerge from the fog until you've travelled for a while, so we knew that it would be a long process. By this point we had built out Trent's studio in an abandoned funeral home in New Orleans into a ridiculous setup, with a huge SSL room for him, equipped with every bit of synth and recording gear you could want, as well as individual studios for each band member. I'd also brought a couple of outside guys into the mix, Steve Duda and Keith Hillebrandt, both of whom were talented sound designers and programmers, and they helped to contribute some of the raw material that we could use to sculpt the sound of the record. So it was a pretty long and involved process--at one point I did a tally of the song sketches that were on our file servers, and we had well over a hundred pieces of music to choose from, so obviously there were a lot of dead ends and dusty trails that we explored on our way to the finish line.

PSF: What was the inspiration for "Starfuckers"?

CC: Well, there are a few theories on the inspiration for the song "Starfuckers, Inc." The instrumental bed was a track that I wrote, which was inspired by Alec Empire and Atari Teenage Riot. They had opened for NIN on some European tour legs, and I absolutely loved their ethos. A Roland TR-909 and SH-101 synth through Marshall stacks? Yes, please! I thought they had a great approach, a unique sound, and the perfect band name--just right on the money on all fronts. So, I wanted to take some inspiration from their ultra-distorted all-electronic sound and see what would fit within the context of NIN. I created a track with an obscure German drum machine, called the QuasiMidi Rave-O-Lution 309, and I ran it through various guitar pedals and amps, and edited together a rhythm track from it. What sounds like a synth bass in the verses of the song is just the 808 kick drum from the QuasiMidi through guitar amps. So I had created that track and left it on our servers in Trent's "song ideas" folder, and he selected it as a candidate for completion. After he recorded the vocals, I took them and created all of the stuttering, glitching effects, editing micro-sized molecules of his vocal, by hand, to create that unusual effect. As to the lyric content, and whether it was "about Manson" or whatever, I can't really be too specific--only Trent can answer that. But I can say that, in general, Trent and the rest of us were a little disillusioned by the "trappings of fame" or whatever, by all the people who glad-hand and want to kiss your ass simply because you're successful or well-known. The phrase I coined at the time was "hollow joy"--that's what it felt like sometimes, when people are all over your shit because you're on fire, but you know that if you cool off, they won't be around. I think that kind of stuff is part of the reason Trent wanted to relocate the band away from Los Angeles, and to a side street in uptown New Orleans. He wanted to be in a place where fame didn't matter, where we could sort of blend into the background and get on with the job at hand, and New Orleans is perfect for that. It's the "city that care forgot," after all. So, I think that the lyrics of "Starfuckers" are kind of a jab at people who make music simply because they want to be "rock stars" and not because they want to create worthwhile, innovative art, which has always been what Trent's about. So, I guess those lyrics are a little bit of a "fuck you" to that mentality.

PSF: When did you start branching out producing and remixing other bands?

CC: Even before I got involved in the NIN camp, I had been doing a lot of programming, production, and remix work for other bands, like Prong and White Zombie, and throughout my years in New Orleans I kept that going at a pretty high level. I churned out tons of remixes along the way, for everyone from David Bowie to Jamiroquai to Rammstein to Type O Negative, as well as the stuff I was doing for NIN and Manson. During those years I still worked a lot with Rob Zombie, and we did tracks together for all three movies in the Matrix franchise, as well as the remixes I did for White Zombie's Super Sexy Swingin' Sounds album and Rob's first solo album, Hellbilly Deluxe. So, I kept up that kind of work pretty steadily over the years, and when I left NIN in 2001 and returned to Los Angeles, I kind of kicked that stuff back into high gear for a couple of years. I produced a couple of albums for indie bands, and then began work with Page Hamilton on an album for his band Helmet, including a lot of song ideas that we had written together when I was still in New Orleans. That was a great project, and we recorded at Cello / EastWest on analog tape, then we did overdubs at my house in Hollywood, and I was able to add a little bit of interesting programming and sound design along the way.

PSF: What was the Fragility tour like? Was it similar to or different than Self-Destruct?

CC: The Fragility tour was a lot more calm and artsy than previous tours, and I think it gave Trent the opportunity to try some more experimental approaches than would have worked for previous albums. He commissioned video artist Bill Viola to create the content that was displayed on giant, motorized video screens, which added a whole new dimension to the stage, since those screens could function as giant, abstract lighting elements as well as acting as giant television screens. As a result, the stage setup had to be more precise and less chaotic, since there was the added element of danger from the motor-control operator, who was controlling a four-thousand-pound moving ceiling, which could easily crush you to death. In addition, the musical content was a little less insane, with more precise and delicate songs that were a bit more difficult to perform than just thrashing our way through "Happiness in Slavery." So, we had to rehearse for quite a while, although many of the rehearsals took place at Compass Point studios in the Bahamas, and that didn't suck. In general, the Fragility tour was a lot more subdued and civilized, and was a big step forward for the band, both artistically and in terms of the technology and what it allowed us to achieve. I have this nagging suspicion that some of the fans who may have come to shows expecting Self-Destruct part II may have been a little confused, but over the years both the Fragile album and the videos of that tour have become fan favorites, so I think that Trent's instincts were correct, as usual.

PSF: What ended up causing your departure from the band?

CC: After the Fragility touring cycle ended, we all returned to New Orleans and began to wonder, "What's next?" After almost fifteen years of going flat-out, Trent seemed a little exhausted, and understandably so. Robin Finck disappeared to join Cirque du Soleil or Guns N' Roses (I forget which), and Danny Lohner and I were just sort of lurking around the empty studio wondering when we'd start work on another album. After a few months with no activity, we both got a bit restless--after all, NIN was the only reason we had moved to New Orleans in the first place, so if that's not happening, what the hell were we doing there? I had Page Hamilton wondering when we'd be able to work on the Helmet album, and other projects nipping at my heels, and I kept prodding management, trying to figure out what the band's schedule looked like. The only response I could get was basically, "We'll let you know. Let me make this clear, you are absolutely not being fired, but if you have other things you want to work on we'd encourage you to pursue those options." I think Trent just needed to rest, recuperate, regroup, and rethink what he wanted to do next, so in June of 2001 I decided I'd leave him alone to figure that out. I returned to Los Angeles, got a big modern house in the Hollywood hills, stuffed it full of all my gear, and got down to work on all of the backlog of stuff I'd had to put off while I was on tour.

PSF: How did you come to compose film scores, and what was the saw experience like?

CC: In the 1980's, fresh out of college, I had worked with an Australian composer in NYC on the score for the CBS television series The Equalizer, doing sound design, drum programming, and mixing of the score each week. In fact, it was this composer who first brought me to Los Angeles to work with him on other projects after The Equalizer ended, and his work slowed down as I was starting out with NIN, so that was a smooth transition. So, I had a good bit of experience in the trenches of scoring a demanding, hour-long, weekly network TV series--I knew the workflow, the terminology, and how to approach that sort of project. When I was in the middle of producing the Helmet album Size Matters, I got a call from my lawyer, who also represented James Wan and Leigh Whannell as they were just finishing up the first SAW movie, and he told me that they had some of my industrial-style remixes in their temp score and wanted to find a composer with my kind of background. It was a pretty natural fit--James and Leigh grew up listening to NIN and other heavy music, and wanted to inject that sort of style into their movie. I jumped at the chance to score a film all by myself, and did the entire score in my "B room" while Page was tracking vocals for the Helmet album in my "A room." At the time, we didn't know if the SAW movie would find its audience, much less become a huge franchise, but I knew they had something special--and as the years have gone by we've seen both of them become very successful filmmakers, so I'm extremely glad that I found them right at the start of their careers.

PSF: What are you currently up to?

CC: Since the success of the SAW franchise, I've basically been scoring films and television series exclusively. Generally, I do television for eight months out of the year, and cram in a movie during the summer hiatus. In the last fifteen years, I've scored seventeen films and nearly three hundred hour-long episodes of television, across five different series on four networks. But I did recently get pulled back into remix work for a one-off: James Wan, the creator of the SAW franchise, directed DC's Aquaman and wanted me to do a remix of Depeche Mode's "It's No Good" for a scene in the movie. So, it was fun to return to my old ways for a minute.

PSF: Do you keep in touch with the NIN guys?

CC: I'm still good friends with the guys, especially Danny Lohner, who was really instrumental in convincing Trent that I should be the keyboardist in NIN back in the day. I had known Atticus since his band 12 Rounds was signed to Trent's Nothing Records imprint, and I see him every so often, and I recently saw the band perform at the Hollywood Palladium on their sold-out run. As expected, they killed it, and even though the lineup has changed it was great to see Robin in his customary spot on stage left. Even all these years later, Trent was in top form and absolutely bringing the power and pain, and the audience was going mental. Great band, great show.

PSF: What do you think of the impact of alternative rock in the '90s?

CC: A lot of the alternative rock from the '90's era is almost becoming the "classic rock" genre for our generation. You still hear the best tracks from that era on radio all the time, and with bands like The Cure being inducted into the Hall of Fame, the titans of that genre are being regarded as the important innovators that they were and, in many cases, still are. The fact that Trent's been able to keep reinventing NIN, keeping it feeling fresh, current, and vital to this day, is a testament to his talent and intelligence, and he keeps gathering more fans as the years go by. Younger folks who discover NIN by way of a current album and then dip back into the archives to learn more about the band's repertoire will always come away amazed, like, "How did I not know this stuff existed? Granted, I was only four years old when The Downward Spiral came out, but still . . . DAMN!" Hopefully, the legacy of all of the wild experimentation of those years will influence a whole new generation of creatives, whether they're recording artists, filmmakers, or writers, and we'll be hearing the echoes of those influences for years to come.

PSF: What do you hope NIN's legacy will be?

CC: It's pretty clear by now that NIN will go down in music history as one of the pioneering forces of dark, heavy, emotional music. Even though some might generalize NIN as an "industrial" band, I don't think that Trent every really thought of it like that. He may have been heavily influenced by artists that were in that genre, but I think what he was going for was something more personal, something that wound up fitting in between all the boundaries between genres. I would hope that, just as electronic artists point back to Kraftwerk as "the pioneers," that an even more diverse group of artists will point back to NIN in a similar manner. We were trying to make music that we'd never heard before, and I think that will always be a big part of NIN's legacy. It just sounds unlike any music that came before or after.