Orbital

by Aaron Gonsher

(December 2012)

Belinda Carlisle and Jon Bon Jovi were yelling at me about heaven and love, respectively. I knew that Orbital, the English electronic duo of brothers Phil and Paul Hartnoll, were known to interrupt concerts of their carefully calibrated techno with this ruthless crossfade between "Heaven Is a Place on Earth" and "You Give Love a Bad Name," but I wasn't prepared for these levels of bombast. Gnarled synthesizers and squelching acid bass arpeggios slapped against my frontal lobe. The ping-ponging drums could have lingered for a lifetime, turning me into a raver sleeper agent, ready to dance uncontrollably whenever Belinda Carlisle accosted my eardrums. The crowd went was going berserk, but the reaction was tame compared to the roar that greeted the bleep-and-bass anthem "Chime." Bodies – and they were bodies alone, systems governed by exclusively physical impulse as firing synapses and serotonin overloads rendered mental faculties inoperative – stomped and scythed. Nubile bodies tussled harmlessly, commingling sweat, their pheromones vibrating in conjunction with the musical tremors. Personal space was an outdated concept. Arms were raised in rapture, and for a split-second it could have been the summer of 1990, Orbital rain-dancing and conjuring through the English countryside. But it wasn't. It was mid-April in Southern California, 2010, at the tail end of Orbital's first reunion tour following years of inactivity. "Chime" was the first song Orbital ever released. No one at my concert seemed to care that it was over twenty years old.

"Chime"'s creation myth typifies the tales of amateur revelation that run through dance music history: the Hartnoll brothers haphazardly assembled uncleared samples from their fathers' easy-listening records on his cassette player before rushing out to a pub with their buddies in the sleepy village of Denton, England. It was 1989, with rave and its glossy accompaniments seeping into the fabric of British youth culture. Songs associated with the then-burgeoning style of acid house had already taken the one, two, and three spots on the pop charts in October of the same year. Although pre-dating the Criminal Justice Bill of 1994 that sought to criminalize raves -- the music defined as "sounds wholly or predominantly characterized by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats" – the new dance culture was already engaging with backlash as the nascent scene entered public consciousness. Despite costing practically nothing to make, "Chime" was explosively popular, released in December of 1989 and reaching #17 on the UK charts. In comparing "Chime" to Derrick May's seminal Detroit techno mushroom cloud "Strings of Life," famed UK critic Simon Reynolds has said that the track "became invested with so much psychic energy that it took on a meaning far beyond words." The song's success catapulted Orbital to fame and they were asked to play Top of the Pops. Although they typically improvised their live shows, the brothers responded to the producers' insistence on airing a prerecorded version by embracing if not parodying stereotypical public misconception that dance DJs were faceless knob twiddlers. Reynolds reports in Energy Flash that this performance "infuriated the producers and confirmed all the Luddites' fears: the brothers simply pressed a button (all it took to trigger the track) and stood there listlessly, not even pretending to mime."

The summer of 1989 had seen the transplantation of the acid house scene from sketchy warehouses to the shining countryside. Just as remnants of General Motors' influence found expression in the chugging, blighted soundscapes of early Detroit techno, British rave also intersected psychically with car culture. The M25 London orbital motorway was the primary means of access to the major unlicensed raves because late-night announcements of secret sites necessitated a car and a quick, sure route. By assuming the name of this thoroughfare, Orbital invested in themselves the gestating mythologies of these communal raves: the willingness to attract police attention in exchange for your dancing fix, the erasing of hierarchical clubbing dynamics in favor of a hedonistic democracy, even the willingness to engage in a criminal act by innocently handing a friend a pill of Ecstasy. The name Orbital incorporated not only the literal mode of transport but associated the music with the psychedelic freeways that brought an onrush of drug-induced revelation. The name epitomized what brought these disparate people together: the idealistic Ibiza veterans and hardscrabble lower-class newcomers, Orbital as shepherds and gatekeepers for a stunningly new experience. Both the namesake freeway and Orbital the electronic duo became key avenues for experiencing this revelatory throb and flash.

The Hartnoll brothers didn't spring fully formed from the womb in rave regalia, clutching Roland 303's like pacifiers. Older brother Phil was a saxophone player, influenced variously by the Clash and minimalist composers like Philip Glass. Paul played guitar and drums and liked the Dead Kennedys. He recalls disparaging British house music as just "electro and hi-NRG mixed together," but waxes romantic when reminiscing about his introduction to electronic music via the warm analog bubblebath of Kraftwerk's Computer World. These disparate influences coalesced in Orbital's music: precise, soothing tapestries intermingling with quaking beats and impetuous bass, sensuous buzz and grounding reminders of humanity, too much sun and LSD warping the grooves.

In the early days of British house music, artists encountered a vicious creative turnover recalling the early days of rap. Songs devolved from cutting-edge to passé in a span of weeks as voracious consumers inhaled the addictive new sound of acid house. The 1991 release of Untitled I, also known as ‘the Green Album,' established Orbital as outliers focusing their creative capacities on long-playing albums. The move was far from ordinary in a culture that craved the transcendent single but set the brothers on a career path of unusual longevity. Untitled I is restless and jittery, elements flitting desperately in and out of the mix, one- or two-bar melodic breaks sneaking in new tones and motifs. The album begins with a booming sample from Star Trek: The Next Generation of Worf conjecturing on the theory of the Moebius, later to be twisted into a phase loop as the opening track on Untitled II, also known as ‘the Brown Album.' Spiraling synths infect both LP's, a buddy battling a bad trip and pulling your own beatific visions down the rabbit hole with them. Chattering voices battle to assert themselves as songs pick up steam and go from incandescent clouds to bone-chilling thunderstorms. As in most of Orbital's music, there are no lyrics, just hysterical samples and babble, as well as ethereal female vocals looped, reversed, twisted, wrought into rubble, buried, and exhumed. The women sound like they're either in the throes of sexual pleasure or the depths of pain, confusion, and grief. The disembodied voices speak volumes without saying an intelligible word. Orbital split time between the sound and vision of disorienting drug incantations that would further evolve as the hardcore era snarled across England and tranquil textural exercises like "Belfast," whose sirens melt in oozing ritardandos, willing your hips to stop gyrating and your heart to stop tumbling in its cage, the beckoning sunrise splashing across fields sliced through by the M25.

A 1992 interview in Select magazine describes the Hartnoll brothers' record label Internal as "an escape route from brain-dead rave fodder," and in interviews from that time Paul Hartnoll derides the living-for-the-weekend cycle of drug dependence bubbling out of the debauched hardcore and Madchester acid-house scenes. In a dark period typified by a preponderance of greasy horror movie samples, willfully queasy effects, and metallic breakbeats, Orbital weathered these shifting tides surprisingly well even as they transitioned into less hectic forms of techno. In "Satan" off of their III EP, you can hear the template for the next ten years of big-tent electronic music: the hissing steam machines of Daft Punk, the chiming Beatles explorations of the Chemical Brothers, the ominous vocal samples of jungle that turned sampled hysteria and violence into an art form, and the grimy shuddering of future dubsteppers. Their live reputation increased exponentially. More importantly, there were inklings that participation in this scene, so predicated on capturing the moment and reveling in the thin spaces of experience, could translate into a career. Rock notions simultaneously crept in, live musicianship becoming a divisive non-issue in determining dance music "legitimacy" to this day and rising acts challenged to fill commercial visual demands despite propagating an deliberately anonymous musical form. In 1993 and 1994 came two defining moments in Orbital's ascendance: the release of ‘the Brown Album' and their bill-topping, king-making set at Glastonbury 1994. As techno lurched assertively to the forefront, Orbital showed they could command a crowd as skillfully as any swaggering rock artist with a thousand-yard stare.

Orbital 2 sounds like enveloping liquid, dance music throwing stones of varying sizes into a lake and content to watch the ripples venture out from initial impact. It's blocky and carefully constructed compared to Untitled 1, offering thrilling concatenations of densely layered sound. It is a sonic document decidedly intended for extended listening, and yet the rigid continuity of songs that are so immersively heard through headphones showcase equal strength in a live context. While wandering from impatient arpeggios to sublime exercises in delayed gratification, its linear evolutions and stark digressions provide ample opportunities for further improvisation and new melodic directions, which the Hartnoll brothers actively explore when they play live. It is their capacity for tweaking and on-the-spot rewriting that makes much of the album seem somewhat puny in its original form. Despite the albums' lasting beauty and impact, dance music is an experiential art form above all. The ideal context for examining Orbital's music are their live sets, which upended long-held criticisms disparaging the stagecraft and live viability of dance acts.

The transformative moment came at Glastonbury 1994, where Orbital followed Bjork on the mainstage. The documented results are exhilarating, madcap journeys that reveal the brothers as twisted dance floor puppeteers. The high-quality audience bootlegs spanning their entire career are often exciting and almost never mundane; Orbital have remained unequivocal masters of performance and improvisation going on twenty years. They specialize in the slow burn, their shows a continuous peak. Suddenly the untraversable wormhole of EP's and remixes makes sense: live improvisation works in favor of releasing so many alternatively drastic edits built from the same foundations. Live, songs can linger between one minute and twenty, with most residing in the still-commercially-objectionable ten-minute range. In the current era, many DJ's are rightly savaged for poor stagecraft and erratic pacing, so they compensate by incongruously upping the ante with every bass drop, urging the crowd to go bonkers within five minutes of taking the decks. It's an undanceable and unsustainable pace. Listening to an Orbital bootleg alongside the typical hyperactive set is like the difference between having a one-night stand where you fuck your brains out but put your back out in the process versus a month of equally thrilling if even-keeled monogamy, mischievous possibilities minus physical destruction.

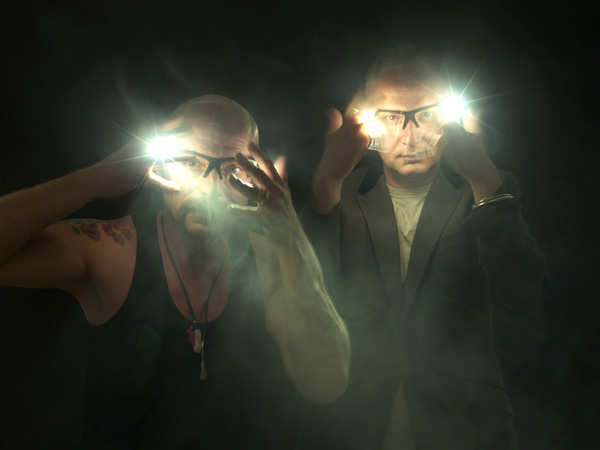

For the first twenty minutes of Glastonbury 1994, the Hartnoll brothers are plodding along, all helicopter bass and uneven piano exercises. By this point, they had begun to wear torch lights attached to the side of eyeglasses during their sets. Originally intended to solve the legitimate problem of being able to see their gear, they became a sartorial trademark, the bobbing lights an enduring iconic image in dance music. They transition into "Impact (The Earth Is Burning)," and those shining lights tumble off the dance floor. "Impact" features quivering squeals, droning horns tilting on the edge of tuneful, drawn-out layers of brass on the verge of something you can't quite grasp through the thick smog. Various mixes of the same song live up to the post-apocalyptic title- a war zone where nothing is in its right place and no amount of processing sets the world right. "Impact" marks the moment in most Orbital live sets when the brothers have tested the limits and excitedly explore further, pulling you over the precipice with them. Grooving onward it's relentless, tribal, nonstop. "Remind," also from Orbital 2, burrows into a two-note bass vamp as the synths hop, skip, and jump through this suddenly opened vortex. "Walk Now" initially lumbers before combusting into high-pitched pyrotechnics and "Are We Here" pounds through breakbeat drum-circle excursions and coos. There is no sense of mechanics in the locked grooves, only itchy fingers twiddling knobs in search of untraveled interstellar pathways. The duo closes, as they always did in those halcyon days, with a goosebump-worthy version of "Chime." The two brothers who scraped together a hit on their father's cassette deck and smirked through Top of the Pops had irrevocably, irreversibly, and incontrovertibly strengthened the power of the revelation of rave to the English mainstream. If you believe the clamoring acclaim from the British press, they went from relative successes to legitimate phenomenon in the span of an hour-and-a-half.

Later in 1994, the Criminal Justice Bill was passed by the English Parliament in an attempt to legislate raves, criminalizing what were formerly civil offenses like collective trespass and nuisance on land. It was too late: the takeover was complete. Orbital would go on to play Glastonbury four more times over the next ten years, making a triumphant return to the same main stage headlining slot upon their reunion in 2010.

My personal experience of Orbital at Coachella 2010, only their second show in the U.S. since 2004, had a similarly epochal feel. "Remind" still took a frenzied swoop upward into the troposphere, and a bruising version of the Doctor Who theme song subverted another touchstone of English culture to the powerful thump of techno. The crowd skewed older, perhaps ravers who never quite adjusted to the changing times and beats. Dance music fetishizes its forefathers as well as its futurists, but even in reaction to a culture defined by exulting in the ephemeral I can't bring myself to be nostalgic for an era I took no part in and have only secondhand knowledge of. Despite the release of new album Wonky in 2012, Orbital haven't released any music "relevant" to the current generation of dance music addicts. Instead, they sit comfortably in an unassailable pantheon and canon of electronic dance music in the same way someone like Jerry Lee Lewis looms over rock n' roll. Idealized visions of rock, however, are often inseparable from the physicality of its performers. To see most of the old rock vanguard now is a relentlessly visual reminder of what was: serrated vocals, gnarled faces, and arthritic joints bending the once-rebellious bodies into unrecognizable recreations of forms past. Two decades on, it's not so for the dance music elder statesmen in general nor Orbital in particular: the Hartnoll brothers and their crowd-centered performance paradigm managed to immortalize their youth and peak musical output. So as "Chime" raced down my spine and shot daggers of energy to my extremities, I wasn't transported back to the rolling fields of the English countryside, but I was transformed in the here and now, utterly present in the moment of elation and unadulterated joy, dancing as long as the music sustained. Heaven is a place on earth.

Also see the official Orbital website