Paul Siebel's Jack-Knife Gypsy

Not Just Folk!

By Kurt Wildermuth

(August 2020)

Wanna hear something weird? I don't mean Paul Siebel's music, which takes unexpected turns but isn't that unusual. The weird thing is that I recommend Siebel's second album, Jack-Knife Gypsy (1971), over his first, Woodsmoke and Oranges (1970).

You may be scratching your head. But instead of questioning my judgment about his records, you may be thinking: Who's Paul Siebel? For a full(er) answer to that question, you might visit his Wikipedia page and also read the online appreciations at Uncut and American Songwriter. The information and tributes you'll find through a quick web search may be enough to send you in search of Siebel's music.

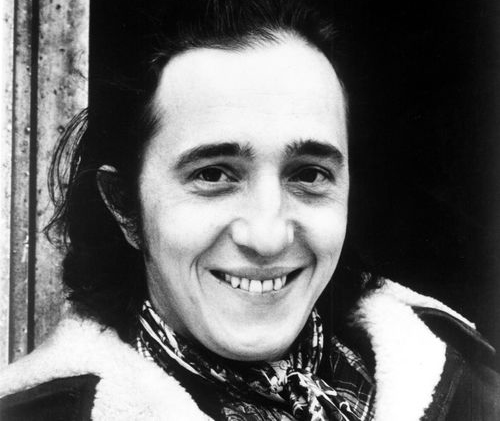

For the purposes of this piece, suffice it to say that Siebel was a New York City singer-songwriter who released those two albums, then left the music business. People who deeply love his work often call him 'a musician's musician,' and his songs have been covered by superlative singers with excellent taste in material, prominently Linda Ronstadt, Bonnie Raitt, and Emmylou Harris. His fans consider it tragic that Siebel's not just underrated but unknown. And yet, despite the man's obscurity, both of his albums are easy to come by. They've long been available as downloads or CD's.

So if word is out, his story's told, and the music's ready for purchase, what's the purpose of this PSF piece? Conventional wisdom has it that Woodsmoke is Siebel's absolute classic and Jack-Knife is the worthy follow-up. One Siebel collection starts with the entirety of Woodsmoke, provides a few choice cuts from Jack-Knife, and still finds room for a bonus track. But why? Conventional wisdom sometimes favors the conventional. Instead, I'm here to celebrate and sing the praises of the unexpected--in this case, of the sophomore work over the debut--and in the process help spread the word about this small oeuvre.

Since Siebel's seen as buried treasure, it's odd to seem down on one of his only two studio albums (there's also a 1978 concert recording, Live at McCabe's). Don't take my emphasis to mean anything's wrong with Woodsmoke. That album includes his most-frequently covered songs, including "Louise," a heartbreaking lament for a prostitute, which seems to gain depth the more you hear it and the more versions you hear of it. Ronstadt's and Raitt's versions may compete for best in show on this one, but Siebel's own is no slouch. That song alone makes Woodsmoke worth hearing. If the whole thing doesn't sound like or in fact isn't your thing, please give Jack-Knife a chance. To the generally restrained folk and folk-country of Woodsmoke it adds the electricity of country-rock and pop-rock. Perhaps most importantly--another weird claim, but here goes--it adds some pretty big drums, played by the studio great Russ Kunkel.

Whereas Siebel reportedly felt that the full-band arrangements and heavier production of the second album went too far, in the 21st century, their lack of purity may speak to us more, inspiring us to slot these tracks into playlists filled with similar genre-crossers. In other words, if you want more music in the vein not just of Ronstadt, Raitt, and Harris, but also of Bob Dylan, the Band, Joan Baez on her Nashville records, Neil Young, Loudon Wainwright, Jackson Browne, et al., listen to Jack-Knife Gypsy. In fact, one thread between many of these artists is Russ Kunkel, so Jack-Knife Gypsy may have felt familiar to you even if you hadn't known he was on it.

I happened upon the album by a lucky coincidence. Early in 2020, I was writing a PSF piece about Carol Hall's two early-'70's singer-songwriter albums. One reason I bought those albums when I found them at a thrift shop was that they were released by Elektra Records. If a record is on Elektra in that period, I'd written, it's worth checking out. Before I'd finished the Hall piece, I found the Jack-Knife LP at a thrift shop. Since it was released by Elektra at the same time that Hall was on the label, since the cover art suggested Siebel was some kind of outsider (the crosses in the gatefold photo suggested Christianity, though the name Siebel didn't), since it was a white-label promo copy (the kind of thing sought by record collectors), and since I was buying a bunch of albums that were released in the early '70's (someone seemed to be clearing out a collection by year, as if records have a sell-by date), I had to give it a shot.

When Jack-Knife turned out to be my thing, I immediately listened to Woodsmoke on YouTube, but I found it underwhelming. Had I encountered that first one first, I probably wouldn't have sought out the second album.

Again, Woodsmoke may be your thing, if you like beautifully-written songs sung sensitively and performed confidently by talented musicians, including guitarist David Bromberg. If you like the early work of Fred Neil or Tom Rush or Gordon Lightfoot, you might like this. But if straightforward folk sometimes underwhelms you, maybe put off trying Woodsmoke and consider Jack-Knife.

Side 1 of the latter opens with "Jasper and the Miners," a crime story that, with a sparer arrangement, could be one of Dylan's parables on John Wesley Harding (1967). In fact, Dylan's influence on every aspect of this track is undeniable, yet the result holds its head up. It could be a textbook example of how pervasive influence can come across as not slavish imitation but the belief that This Is The Way To Do It. I'm not sure where the difference lies--why we may forgive one work for aping another yet feel repulsed by the same technique in a different context. Is it that "good artists copy, great artists steal," as Picasso reputedly said? Paul Siebel displays a conviction about this song, and that conviction is backed by his band, and together they push a two-minute, thirty-second slice of fiction into an intriguing, Dylanesque opener.

If track 2 copied track 1, the listener's enthusiasm could flag. But on "If I Could Stay" the music swings into soul, and Siebel rises to the occasion. His voice doesn't have an easily identifiable character, but on this song Siebel uses that instrument to matter-of-factly and then soaringly express feeling and intellect. The lyrics present conditional scenarios ("If I" this, "If I" that), which end inconclusively: "I might need a cure / But I'm not really sure... that would change me." Piano notes disintegrate in the air as though symbolizing the indefiniteness of everything the singer has just pondered.

Next up is the title track, which could be a higher-voiced Bob Seger, which might be a less nasal Arlo Guthrie, fronting the Band, but the Band with a smoother rhythm section. These comparisons just give you a sense of the sound; they don't define the music. Here the singer addresses the title character, a thief with whom the singer feels kinship, having been in similarly dire straits: "This ain't been nice / But we got somethin' said. / I once held the knife / The same way that you do."

The album's sound takes an unexpected turn on "Prayer Song," which has a quasi-psychedelic Middle Eastern drone. Acoustic and pedal steel guitars ring out transcendently, and Siebel, sounding like a dead ringer for Loudon Wainwright's son, Rufus (two years before Rufus was born), is an Anglo muezzin in a tower, calling to the rain, the wind, a bird, and a tree. Without each, he'd be alone. The rhythm section kicks in, and piano notes dance in the air or are sprinkled around until, of all things, a trumpet solo enters the mix. Throughout the album, by the way, solos such as this one do exactly what solos are meant to but frequently don't: emphasize or enhance the song's point at that point. If I were teaching a course in recording songs, I really would use this album as a textbook.

On most records, side 1 would end with the atmospherics of "Prayer Song" and side 2 would start with something more up-tempo. Instead, just when you go to the turntable to pick up the tonearm, thinking side 1's over, "Legend of the Captain's Daughter" delivers a surprise. As the singer tells the tale of a drowned woman whose spirit lives on, Russ Kunkel and bassist Billy Wolfe earn their keep by seeming to speed up--they don't, but they make it feel as though they do. A fiddler--probably Doug Kershaw, who's credited as a sideman--embroiders with masterly homespun charm. The spirit proves infectious, so you don't want the song to end, but near the four-minute mark the tale is told, Siebel scats as the fiddler works his magic, and there's a quick fade. This seriously may be my favorite album-side ending since... well, since the advent of CD's rendered album sides beside the point. In fact, every song on side 1 of Jack-Knife Gypsy sounds so fresh and inviting, and the ending is so much fun, that I'm left wondering whether to flip the record over or repeat that initial journey.

(Note to vinyl neophytes: forty-odd years ago, I heard that to preserve your records, you should let the grooves cool for a while before replaying. Whether or not that's true, I've followed that advice and kept my albums pristine.)

On Side 2, the terrain remains country, as guitars and violin usher in the slow dance of "Chips Are Down." Siebel again prefigures Rufus Wainwright, if Rufus were to inhale a whiff of Dylan and somewhat whinily croon his way around a waltz with cryptic lyrics, such as "Every one's preachin' participate / While love and hate--shoot the dice" and "poets were made for the guillotine." From here, Siebel proceeds to a series of portraits.

"Pinto Pony" is a western outlaw tale observed by a person who covets the outlaw's horse and may just get it. Some of Siebel's inflections here are pure Dylan, but Dylan probably wouldn't sound so spirited on the repeated line "Man I'd like to have that pinto pony." Harry Nilsson comes to mind.

"Hillbilly Child" pays tribute to a woman on the wild side. The effect kind of reverses Woodsmoke's tender "Louise," as the band delivers a big, Nashville-worthy country sound.

"Uncle Dudley" slows down the same setting as it portrays a man who "never made it." The singer misses his uncle's "great lies / No one to rock me when I'm lonely / No one to lift me when I'm down."

In "Miss Jones," the singer laments his fate as the poor farmhand or enslaved man who must do the sexual bidding of the title character: "She calls me up to wash her floor / but that's not what she wants me for." Imagine the young Randy Newman fronting an oompah band, with the fiddler again front and center.

Alas, "Jeremiah's Song," ends side 2 with a bit of a whimper. Siebel's Dylan influence is simply too heavy on this little story. In a sense, the album ends where it began, but whereas "Jasper and the Miners" stirs some Dylan into Siebel's stew, "Jeremiah's Song" comes across as a John Wesley Harding wannabe. If the day is saved on this one, it's by the un-Dylanesque fiddle and Jew's harp, plus Siebel's low-key delivery of the parable.

Jack-Knife's drawbacks are the sequencing, which renders side 2 a letdown after the brilliance of side 1, and the over-similarity to Dylan. The album's strengths outweigh those weaknesses, but I might as well acknowledge that it's not perfect. You, as a media-savvy listener not beholden to the artist's original vision, can overcome the first obstacle through digital shuffling (take that, vinyl enthusiasts!). The second obstacle matters mainly if you've heard enough Dylan (take that, Dylan enthusiasts!). If so, maybe start with Woodsmoke, where the influence isn't so pronounced.

Either way, please choose your gateway to Paul Siebel. Or refuse to choose and check out both albums. And if you go on to the live album, let me know how it is.