RANDY HOLDEN

Guitar God finally gets his due

Interview by Robin Cook

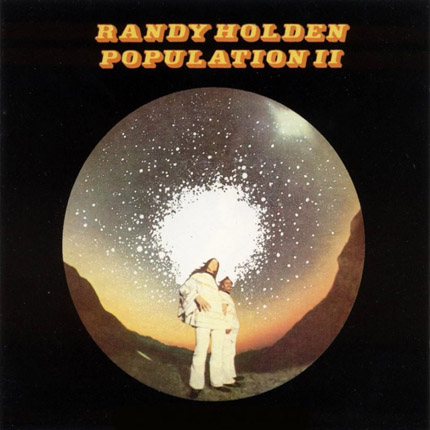

Randy Holden's Population II, released in 1970, is the work of an artist one step ahead of the curve. By the time he went into the studio to record the album, the guitarist was a veteran of such bands as The Other Half, Sons of Adam, and Blue Cheer. Population II is a sweeping, experimental work, and a crucial cornerstone in the evolution of hard rock/heavy metal. Or it would have been, if Holden hadn't become the umpteenth artist to become the victim of record industry politics. But there is a happy sequel: after decades away from music, Holden returned to playing, and Population II is being re-released this year.

PSF: Okay, first of all, I was just wondering, could you give me some bit of background on the reissue and how it came about?

RH: Well, the record label called RidingEasy wanted to do a 50th anniversary releasee and so I agreed that they could do it.

PSF: I've been listening to the album, and it's been considered to be a forerunner of doom metal. Is that something you're comfortable with, that it's considered part of heavy metal history?

RH: That's what it said to have been by many people. Not necessarily doom, but heavy metal, I guess. I don't know.

PSF: I'm curious about the term? I mean, is that something? How did how did you feel about being pigeonholed? Some other artists have been sort of ambivalent about the label.

RH: Well, I'm not sure what the labels are...I wouldn't call it doom necessarily. Although there is an element to it that was different than anything else that was going on. It was a step away from the real happy-go-lucky music, I guess you might call it. But it was kind of strange how it came about. It was a very subconscious thing.

PSF: I noticed that the songs tend to go off on many different tangents instead of handling just doing Verse Chorus Verse. Did that come out organically?

RH: yeah, I would definitely say so.

PSF: I'm also curious what sort of music were you listening to at that time. Do you think it had any influence on the recording of that album?

RH: No, no, I don't think so. I wasn't listening to much. I was too busy creating what I was doing.

PSF: Let's rewind a bit. Was there any album you listened to as a young musician that made me think maybe you think, "Wow, this is what I want to do. I want to play music."

RH: I knew that at a very, very young age. I think I first picked up a guitar when I was 7 years old. But I made the final determination when I was 13.

PSF: Were you ever formally did you have any lessons or were you self-taught?

RH: No, I'm self-taught.

PSF: Were there any particular guitar players that you really admired or sought to emulate?

RH: Oh gosh, there were several. There was a music like Duane Eddy. He was excellent. And most Instrumental groups. I was very interested in instrumental.

PSF: Like the Ventures?

RH: Yeah, they were excellent for sure. They brought melody into guitar music. They did a lot of interesting classics.

PSF: Could you walk me through a bit some of the bands that you played with, before you were in Blue Cheer?

RH: Let's see. I had The Iridescents- seems that was '61-'62. Then, I was doing surf music in Fender IV, and that was in 1963. Then we moved to California and I called us the Sons of Adam.

PSF: I can still definitely hear that surf music influence in your guitar playing.

RH: On Population 2?

PSF: Yes, definitely.

RH: Really?

PSF: Yes.

RH: That's interesting. No one's ever said that before.

PSF: Well, I would say that certainly with surf music, especially under The Beach Boys that gradually segued into psychedelia and certainly there's a psychedelic element to your guitar playing.

RH: I probably wouldn't dispute that at all. I don't know if that's enough words to describe it I guess. But surf, I was interested in the instrumental side, rather than the vocals. The vocals didn't influence me at all.

Chuck Berry was an influence, of course. He influenced everyone. And Dick Dale, he was another really excellent--he had excellent style, and a lot of passion. And I think maybe psychedelic--where might that have come in? Probably, I don't know, hard to say. It depends how it's defined. It actually means 'breath' when you get to the root of the word.

PSF: I wondered about your time in Blue Cheer. How did you come to join that band?

RH: We had played several gigs together sometime before I joined them. And I used to play very loud. I used to play very loud--lot of volume. And I was probably the loudest there was at the time. And Blue Cheer came on. I really liked the drummer, Paul Whaley. He was a very creative very powerful drummer. And I was actually looking for a drummer to start a new band with after I parted company with The Other Half [Holden's previous band].

And I saw Paul and the Blue Cheer guys, we knew each other and Paul once told me that he wanted to join the Sons of Adam, that he thought, he didn't ask because he already thought we had a good drummer, and so we'd turn him down.

But who knows? Anyhow, I saw Paul and Blue Cheer playing at the first debut show of Jeff Beck's new album Truth at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles and I was surprised that Blue Cheer were billed over Jeff Beck because Jeff was much more well-known. In any case I asked the promoter who was a friend of mine. And he said he just liked them! (laughs)

So I went to the show and Jeff Beck's band, they were very polished. But Jeff was really kind of withheld, whereas with the Yardbirds he was very... he was more free, I would say. But it might have been because he was playing more complex music with his new band when they did the Truth album with Rod Stewart. They were very good, but it didn't have that explosiveness that he had prior to that. I don't think he had the super inventiveness he did with The Yardbirds, which would be hard to continue that level of creativity.

Then Blue Cheer came on afterwards and they opened up with a song called "Just a Little Bit." And that's where Paul does this really spectacular heavy drum entry and it was dynamite. I told the bass player that was working with me at the time, "There's our drummer right there!" (laughs)

So after they finish their set out, I went backstage and I found Paul and said, "Hey, man, I want you to come join my new band."

So it was arranged that we would jam together the next day at the Shrine with all the gear onstage, and the surprise was my bass player and Paul could not play with each other at all. I never saw anything like it in my life. Kind of really blew me away.

So Paul and the Blue Cheer manager came to me and the said, "Well, we don't care for your bass player you have. He can't play with Paul." And they were totally right. I didn't understand what happened. But that's what the way it was. In any case, they said they wanted me to come join Blue Cheer instead. So I said I said I had to think about that a bit. And I thought, "I would just love to play with Paul." So I took 'em up on it.

PSF: And Blue Cheer became pretty influential. I mean not just with heavy metal, but certainly, you know indie bands like Mudhoney were influenced like Blue Cheer.

RH: Blue Cheer influenced a lot of bands, it was a real game changer. But I was kind of a shoe-in because I loved playing loud volume. And I would do things like play an extended guitar solo virtuoso on stage and not always slow down. And I had a blast doing it.

PSF: I'm just curious that you mentioned Jeff Beck. Did you ever get the chance to meet him?

RH: Actually, no. Never did. There was an opportunity, I might have joined The Yardbirds. He quit onstage at Santa Monica Civic. And some fans of mine came and said, "Look, they don't have a guitar player. You know all their songs." And they said they told Keith Relf (the Yardbirds' singer) about it and he wanted me to come down, but I kind of didn't believe him. It didn't make a lot of sense. Jeff had just quit before a show. I didn't want to show up and say, "Well, Hey, I'm here" and then it wasn't really true. I thought I'd look an idiot. So it was set up that I'd meet with Keith Relf the next day and we met. And they were to contact me after they were just leaving for London or England, wherever they were, and we were going to be in contact after they got back. But then they, Jimmy Page was leaning in with them, then they broke up. So that was the end of that.

PSF: You've mentioned being more influence by instrumentalist than singers. What did it what was it like to step up to the mike? I know that most of your musical output is instrumental, but certainly Population 2 does have some vocals.

PSF: Yeah, well, I always sang from the beginning with the Sons of Adam, we all sang.

So I was accustomed to it. It was just very natural. And I always seemed to change my vocal styles, according to whatever the song felt like to me. I never created what you might call a vocal identity.

PSF: And you've also been a painter. Which came first, or did the painting and the music exist side-by-side?

RH: More or less side by side. It seemed like I would be inspired to paint for a while. And then I would not be so and I wouldn't do it for quite a while. Then it would happen again and then I would do a flurry of paintings. Then I would stop. Then I would come back. So it was an on and off kind of thing. But I always enjoyed it.

PSF: In the '60's, were there any like other guitar players besides Jeff Beck that you really admired?

RH: Let's see, I think there was only a handful. I think there weren't any American guitarists that did anything for me. It was always English guys. They had a certain perspective, I guess you'd call it, on music and generally they liked to play loud. I liked that. Hendrix, probably, was the only American guitarist I really enjoyed. And let's see, there was Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, that was it. We were all contemporaries. I was doing what they were doing but other Americans weren't doing, for whatever reason, in terms of style and volume.

PSF: There was about a 25-year period between Population 2 and when you started recording again. What were you up to during that period?

RH: Well, I got locked out of the music business. It was in the contract to have the the Population 2 album released and everything was done. We were ready to go touring. It was already getting a promotion, and the record company wouldn't--they never released the album. And they kept telling me, "Another 30 days, another 30 days, another 30 days." They wouldn't tell me what was going on. But this went on for six months or so, and finally, I just went bankrupt. But the record label, they refused to let me out of the contract. I had other offers; I couldn't sign up because they wouldn't let me out. So I was virtually just locked out of music.

I didn't have any idea what I was going to do because that's all I'd ever done and I had no idea what to do. I didn't want to stop playing music. I just loved it so much, but there comes a point when something like that happens--you've got no avenues open. I just want to go off in the jungle somewhere. So I ended up settling on Hawaii and I went there and I got into big game fishing. Some guy wanted me--I was painting one day and somebody saw I was painting and they wanted me to paint a big marlin on their truck. (laughs) 'Oh, really? I never saw one.' And in exchange, they take me out fishing. And I just got hooked on big game fishing. And I ended up doing that and they I started doing it commercially, because you can make some pretty good money doing that. And I was pretty good at it, and it was a blast, so it filled the emotional void--when music was cut off.

So that's what I did. And then I did that for about twelve years. Then I just started traveling a lot.

And I found myself in the position of having a one-year-old baby. And I was a single parent. That was, uh, mind-boggling. I never anticipated that and had no clue what I was going to do. But I wasn't about to adopt him out.

So I spent years bring him up, traveling around, educating him. Then I went sailing around the world and homeschooled him. He turned out great. Just a great kid. So that's what I was doing. I spent most of my time on the ocean. I love the ocean. There is a sound on the ocean, of the wind and the waves, and that's the same sound you hear in big amplifiers. It's a hiss. And a roar. So there is a definite sense of identity with it.

PSF: You went from playing surf music to sailing on the ocean then.

RH: Pretty much. A lot of stuff in between.

PSF: I'm wondering how you were able to overcome the label difficulties. I'm sure I can only imagine it must have left you with a lot of very bitter feelings. How were you able to move beyond that?

RH: I was very angry with the music business for locking me out like that. When I decided to go to Hawaii, I just wanted to just be an artist. That way, nobody could mess with me, I figured. Nobody else could control my artistic pursuits. And that got sidetracked with the big game fishing- that was just very exciting. Catching a giant marlin, it's like nothing like that. I caught one of those--eleven hundred, seventeen pounds (laughs). They're just dinosaurs! And they'll kill you if they get the chance. I'm surprised I lived through so many things that I did, being out on the ocean! (laughs)

PSF: What eventually made you decide to pick up that guitar and start playing music again?

RH: Well, I was kind of at a real emotional low point in my life. And this guy was hunting me down. I didn't know it; he said he was hunting me down for four years, and he finally found me. At first, I thought he was the CIA or something. I couldn't imagine anybody doing anything like that.

But he was trying to persuade me to accept the guitar from him so I would start playing and recording again. And we went back and forth for about a year over it 'cause I didn't really want to, because the disappointment was still there. But I eventually capitulated and I picked it up and I just fell in love with it all over again.

PSF: You're now seen, being sort of hailed as this guitar hero and you're finally getting some attention. Do you feel at all vindicated by that, given what you went through?

RH: Yeah of course. I thought the new album, if it had gotten released, I thought it would go huge, because it was really different. People didn't understand what it was. I thought if it would just get airplay and I could play onstage, people would end up loving it. So I was rather amazed to find out that my music was being sold all over the world. I didn't have a clue. So yeah, having it being recognized this far in the future, there is a certain vindication.

PSF: If you could give advice to young musicians starting out, what would you say to them?

RH: Oh wow. It's so different now than it was when I was young. The only thing I think I would say is just play. To me, I didn't have a choice to play music. It was a love affair from day one. So if you've got that, pursue it. Pursue your dream. It could up in disaster, but on the other hand, there's nothing like it. I've certainly had a lot of experiences. And I wouldn't trade them it for anything.

You can, you know, work to make all the money in the world you want, but it does not satisfy that deep inner whatever-it-is that possessed me to play music. It wouldn't even compare. If you've got a passion, pursue your dream. That would be my advice. It might not necessarily be good advice.