Shirley Collins

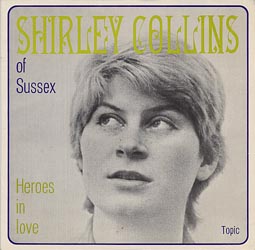

Shirley in 1963

Interview, Part 1 of 5

by Johan Kugelberg of Ugly Things Magazine

"And they must be the footsteps of our own ancestors who made the whole landscape by hand and left their handprints on everything and trod every foot of it, and its present shapes are their footprints, those ancestors whose names were on the stones in the churchyard and many whose names weren’t.

And the tales of them and of men living I would take with me and the songs in my mind as if everything I thought and felt had been set in words and music – everything that was true in me."

Ever since David Tibet of Current 93 introduced me to the wonders of Shirley Collins' music over ten years ago, it has become a source of spiritual replenishment and refreshment not withstanding whatever particular musical genre I am binging on at the time. The music of Shirley Collins becomes a necessary flavor, heightening the flavor of other genres in its juxtapose. And I will stop this metaphor right here since I am noticing that I am comparing my favorite female vocalist with monosodium glutamate.

As an introduction to the music of Shirley Collins I can wholeheartedly recommend the 4 CD Within Sound boxed set, released by the splendid Fledg'ling label. It can be ordered at www.thebeesknees.com. This is a mandatory purchase, even if you do own a lot of Shirley's records, as it contains plenty of unreleased tracks and rarities.

For the truly obsessed, I recommend my discography on www.shirleycollins.com, which will provide you with hours of happy record hunting, not to mention social interaction with some memorably questionable record dealers.

Shirley Collins' superb memoir of her song-collecting travels with Alan Lomax in the American South in the tough 1950's, America Across the Water, which we excerpted in our print magazine Ugly Things (for the occasion re-named "Beautiful Things," natch) a few years ago, can most easily be ordered at www.amazon.com or www.amazon.co.uk (better service and quicker than the American Amazon, for some reason).

This interview took place at Shirley's home in Brighton. Present were myself, David Tibet and Paul Deighton. Shirley was the perfect hostess, serving a delicious lunch and some out of this world sloe-gin.

JK: What are your earliest musical memories?

SC: I suppose my very first memories are of carol singing at home at Christmas. My family is really important, my granny and granddad in particular. I think my granddad more than anybody sort of shaped me. They sang a lot at home. Granddad would sing a song and play the penny whistle. And then I think it's because my mom and my three uncles and my aunt had all had to go to church in the country village where they were brought up because my granddad was a gardener on a very large estate. It was in the early part of the century when people were still attached to estates and going to church was obligatory. Because it was a little church, they'd have an organ and a harmonium in the church and they all sang. They were all made part of the choir; they all loved to sing. My uncles turned out to have lovely tenor and bass voices, not trained, but just rich voices. I think this is possibly the most important memory in my head, and I think it's what influenced (sister) Dolly so much, was the sound of these churchy harmonies, as you can probably hear in her arrangements. The harmonies are sort of four square and fat, rich harmonies. Singing at home like that was really important. During the war we were evacuated from Hastings twice. It was a smaller town than this further along the coast, and we were involved in air raids a lot. We slept most nights, until we were bombed out, in a shelter, which was one of these iron tables with mesh at the side. Granny would sing to Dolly and me during the night to keep our spirits up as she called it. Although she usually sang such miserable Victorian and Edwardian ballads, things like Barbarella and such, that we usually ended up in tears.

JK: I'm wondering if the love of the flute organ could have come from that?

SC: Well, Granny had a harmonium at home, and it was Donny and my job to pedal it when Granny was playing it, because there were two foot bellows, carpeted bellows.

JK: Was it a small table top or a floor model?

SC: It had a stand, a floor model, with carpeted pedals on the floor. It had a little label across the top that said "mouse-proof" which is one of my early memories as well. So, yes, Granny played as well. It was just by complete good fortune that we found the flute organ. I don't know whether it was the sound of it or what, but I just fell in love with it the minute I heard it.

JK: Did your parents and grandparents play instruments?

SC: Granddad played the penny whistle and he played the melodium. He played in a band in a pub, but that was very sporadic. He used to play percussion but that wasn't until later. And then Granny played the harmonium.

JK: They were politically active as well, weren't they?

SC: Not my grandparents, some of my uncles and my mom. One of the reasons I think my parents finally split up after my dad got back from the war was because my mom was very left wing, and my dad was rather right wing and the two couldn't really find their way through after that. My uncles were left wing.

JK: And active too?

SC: No, not active. My mom joined the labor party in Hastings and stood as the labor party candidate for the local counsel. My uncles put their politics into their writing and their painting; because two of them were painters and Fred was a writer. But it all went into the books. But it wasn't dogmatic, which is something I particularly hate as well. I don't think of myself as a political person, though I have left wing leanings. It was more subtlely put across, which is one of the reasons I've never sang a protest song and don't really like them. I don't like being preached at by anybody.

JK: It's a little like the geese being force fed so their liver goes bad.

SC: That's right!! That's excellent.

JK: I've used that one before.

SC: That's brilliant, I might use it myself.

JK: Just as far as personal politics go, with yours and Dolly's brilliant and moving view on this British art, and British music and British song, could that have come from your uncles and your mom?

SC: I think it must have come from their view on life. Your personal experience is what you read and what you hear about. Granny and granddad in their tight cottage would have been very restricted and people nowadays would scarcely put up with. But it was, as I said, the norm then. But we were always hearing stories about how hard certain things were. For instance, granddad was away in India for five years during the first World War, Granny brought five children up on her own, in this tight cottage, without any money from the owners of the big house who could have supported her. She just lived on the soldiers wage that was sent through. During the flu epidemic of 1914 or 1915, they all got ill in the cottage and the doctor came to see them. He was a lovely man who was always willing to help out, although he should have charged a fee. The lady of the big house set down a blancmagne, but it was made without milk and without sugar and it was left on the front step, and this was the only thing she could do to help them. And they had a huge walled garden with fruits and vegetables and whatnot.

JK: That would have been let them eat cake in a nutshell.

SC: That's right. And we read Dickens a lot and we were also taught, as a great many people in England were, that Joe Stalin was Uncle Joe, that he was a pretty good chap.

JK: His media spin and public image marketing was pretty efficient. There was a long list of his honorary titles in every official Russian document, and those included titles like "Friend Of All Children," "The Great Gardener," "The Little Train Conductor" was another one, and "The Great Tractor Driver" was another. There were literally dozens of these and there was a long list of these public image spin doctoring titles in official Russian documents.

SC: Yes it is extraordinary, isn't it? To us he was Uncle Joe. It's just listening to family talk, and listening to experiences, especially from Uncle Fred. I loved listening to his view on the world. He wasn't anybody's fool. He was a very modest man, very self-deprecating with a wonderful sense of humor. But when he told you something, you could believe what he was telling you. It was just generally that we grew up in a laboring class background and family.

JK: With your uncles, were there a lot of books and poetry around the house.

SC: There was Dickens. Granny read Dickens to everybody. He was her favorite author, and it would just go round and round. My mom loved him, as well as Smallet and Fielding, although I was too young to appreciate it as a child. We certainly knew our Dickens.

JK: But also the notion that reading is something that you do.

SC: Oh God yes. I think they were a partisan family. They loved country life, they loved gardening and walking and being out in the country. And they loved cricket. My son plays cricket, and Dolly and I did when we were children. Everyone loved cricket.

JK: I can see country life reflected in your art, but not cricket. SC(laughing): No, haven't written any songs about cricket yet. But Dolly played for Sussex women's team. Apart from all this love of country life, there was this desire to improve themselves as well, and the way they improve themselves is through books.

JK: Your uncle as an author, do you remember him talking about books or recommending books or authors or poets?

SC: When my dad left home, when I was about twelve or thirteen, Uncle Fred took the place of Dad. We would listen to music at his house a lot. He loved all things English. They would always be talking about books. Fred was writing then, although he was working for the guestboard as a meter collector, he was writing about his experiences from when he was a child and that's reflected in his books. He was also interested in politics, so he was interested in Robert Tressles The Ragged Trousered Philanthropist which is Hastings where we all grew up. Mom was trying to write as well, they were all interested writing poetry. Both my uncles were painters by then and painting for a living, which was unheard of before.

JK: Right, because it was a prerogative of the privileged classes. What would say were your uncle's key literary influences?

SC: Fielding, I would think, and Smollet. He has that same marvelous English sense of humor.

JK: In the area where you grew up, is there a strong tradition of orally learned music, or songs that are orally passed down?

SC: No, I would think not. But then, I wouldn't necessarily have known that. By the time Dolly and I were born, the family had left the country and moved into the town of Hastings, and we were brought up there. And I wouldn't have been aware of anything like that, because what we were singing at home was pretty commonplace.

JK: Even in the carols you guys sang, there were no regional variations on those?

SC: No, because what we were singing we got them from books, so they were international ones, really. Later, I found out that the Copper family was a family that lived between here and Hastings, and they've lived in the same village since the sixteenth century. And they had a marvelous continuity of song, so yes, there were pockets of it. Later, you discovered that people went out into the field and recorded these songs from Sussex.

JK: So they would be the equivalent to Virginia's Hammond family.

SC: Yes. They had an incredible repertoire of songs. The first record was in 1560-something in the church.

JK: Did you go back later on in life and look at songs from the Hastings area? Maybe when you were studying at Cecil Sharp?

SC: Not really. It hadn't occurred to me to do that. The longer I sang the more I realized. When I first started singing, there was a lot of American stuff on the radio from Alan Lomax. I was very keen on American mountain music.

JK: When did you start listening to (Alan Lomax's) Adventures of a Ballad Hunter?

SC: 1950-something. '54, '55. I was born in '35, so I guess I must have started listening to it when I was 17 or 18 because I read for the BBC at one point.

JK: I don't know about that one.

SC: It's a long story really with Dolly and I. We used to go the flicks every Saturday in Hastings. Mom used to give us ten bob to go downtown and we could go and have baked beans and chips and go the pictures all for ten bob for two of us. There was a film I saw called "Nightclub Girl." Dolly and I were both singing at this point and were very keen on music. This film was an American b-movie about the girl who had come from the Kentucky backwoods up to a city to sing in a nightclub. I can't remember who it was but it was an actor I was absolutely crazy about. I know it sounds a little ridiculous but it was quite a moment of decision: "yes, that's what I want." Dolly had bought a guitar then through the Daily Worker, which was the newspaper we got at home. There was a Czechoslovakian guitar advertised that we could afford it. Dolly open-tuned it and laid it on her lap and played it like a zither. She started to accompany herself on that, and me too. But the BBC programs were actually starting to bring in field recordings to these two magazine programs, Country Magazine and [Desire of Doubt] where they were actually using field recordings of traditional singers. And I loved it, I just thought it was wonderful. And I thought, well, I better write to the BBC and let them know about us, so I did and later they sent Bob [Kaufman] because he was recording in Sussex and he came along and recorded us. Although, like an idiot, in order to impress, I had learned a Scottish ballad and I think I must have sung it in a Scottish accent as well which was the craziest and silliest thing I could have done. But Bob recorded one or two things from my mom instead and noted us. All these songs I could have song from home, but I though, I've got to impress.

JK: The mail order guitar is an interesting parallel to Appalachia as well in terms of how important mail order catalogs and what musical instruments were available to American rural musicians. In the U.S., some instruments were cheaper in certain areas. So what instruments were in what regions of the U.S, in terms of folk music, sort of depended upon what mail order catalogs were prominent in that region.

SC: Partly yes, because I remember when I was in the States, a couple of fiddle players said that their fiddles had come from the old country. They'd actually come over with their grandparents. And one or two other people we met made their own instruments. Jimmy Driftwood made his own out of bedposts and fence rails and things like that. So there's that aspect of it as well. If you are that isolated, you find a way of making your own.

JK: I did an article on African guitar music a few years ago. After World War II, which was when guitars started becoming available as a mail order instrument in different parts of Africa, what happened there was one person in the village would buy the guitar. Then five or ten other people would come and build a guitar as per what the guitar looked like, copying it, and using whatever they could find to put this guitar together. So, we mentioned Adventures of a Ballad Hunter. How wide was the scope of that radio program? Did it play country blues as well as Appalachian folk?

SC: I'd have to say that I don't remember. But I imagine it would have, because it would have represented all that Lomax would have recorded, but I don't remember. The other person who was on British radio a lot was Josh [White] whom we all adored as well. He had quite a few programs, he was very popular here. I don't truly remember what Lomax stuff I heard.

JK: Do you remember hearing the Carter Family or Mississippi John Hurt or Son House?

SC: I can't remember names. They're all familiar to me now. Then of course later, I got the Harry Smiths (Anthology). I think I must have bought those in the States, so it was familiar to me then.

JK: When did you first look up the Cecil Sharp house and visit there?

SC: Well, I went to a teacher's training college after I left school. My head teacher thought I ought to be a teacher as well, and I didn't know what I wanted to do other than this great longing to be a folk singer, but no clear indication of how I should go about it. So I went to teacher's training college for a year.

JK: Where?

SC: In [Touting], South London. Hated it. I didn't want to teach. I was only 17.

JK: Did you try working as a substitute or anything like that?

SC: No, we had a teacher's practice. But my practice was on the Isle of Dogs, which is, if you know it, an island in the middle of east London on the Thames.

JK: Rough and tumble?

SC: Very, yes. I was teaching 15 year olds. They were all leaving school to go and work in the MacDougal [Flare] Factory, which was the only job available to them, and they knew far more about life than I did.

JK: And you were only two or three years older than them.

SC: That's right but I felt like three years younger. It was terrible.

JK: That's the equivalent of a young girl going to the South Bronx to instruct a bunch of homeboys.

SC: Probably yes. So I packed up and went home. I got a job as a bus conductor that summer, which was great fun. I really enjoyed it actually.

JK: When was your first visit to Cecil Sharp?

SC: It must have been when I was 18, 1953, yes.

JK: And that is where you made a lot of friends and connections.

SC: Eventually, yes. When we first went to Cecil Sharp house, it was still the domain of the English Folk Song and Dance Society. Not to sound too classist, but they so unnerved me. It was a club really for middle class and upper middle class. They didn't really want people in there. To get to the library you had to get permission and letters and it was very tough.

JK: It was very exclusivist.

SC: Yes, very. But luckily, Peter Kennedy, who was the directors son, Douglas Kennedy was their director, wanted to encourage young people to into this music. Because what's the point of this music if nobody gets to hear it? He gave us a platform in the cellar of the club. Young people could go along, have a sing around, and we could sing whatever song we liked, provided it was a folk song. And then, he started bringing up field singers that he had recorded for us to listen to. It was the most wonderful grounding for someone in my position if you were interested in the music as well. There were a lot of people interested in singing but they didn't have a great deal of interest in the music. There was the start of skiffle not so many years later, and a lot of people veered off toward skiffle.

Also see our previous tribute to Shirley Collins