The Sound of One Horn Playing

Three Paths for the Solo Saxophone:

Gianni Mimmo, Marco Colonna, patrick brennan

by Daniel Barbiero

(June 2020)

The modern era of solo saxophone improvisation begins sometime in the late 1960's. The touchstone recording of the improvised solo saxophone was, of course, For Alto, Anthony Braxton's 1969 double album of eight pieces for unaccompanied alto saxophone. Braxton had been giving solo performances live since 1967, but it was the appearance of the album that somehow made it all official and brought the work to a broader audience. Releasing a recording of solo saxophone improvisations in 1969--and a double album at that--was seen at the time as a bold gambit, the boldness of which has only been underscored by the essentially radical nature of the music, a radicalism which hasn't been much diminished by time. For Alto announced the opening up of a fertile field not only for saxophonists to explore, but for listeners, confronted by a new topography, to become conversant with as well.

To be sure, For Alto wasn't the first solo saxophone recording in the jazz or improvised music tradition. Coleman Hawkins' solo recordings of "Hawk's Variations" and "Picasso" from the mid-1940's are well-known, but as jazz historian Bill Shoemaker has written, as far back as the late 1930's, individual solo pieces had been recorded by saxophonists Gene Sedric and Serge Chaloff. For more recent precedents, one could point to Sonny Rollins' solo "Body and Soul" of 1958 and Eric Dolphy's 1960 "Tenderly." What sets For Alto apart from these precursors is not only its sheer volume--two full LPs' worth of solo saxophone--but the radicalism of what it contains.

The radicalism of For Alto wasn't simply a matter of the advanced technique and expressionistic intensity that characterize much of it, although those certainly were important factors. There was, and is, a more basic radicalism to it--a radicalism that goes to the original meaning of the word "radical": a reaching down to the root. At the root of improvised music is the relationship of the improviser to the instrument; it is a relationship brought out in its most direct form in the unaccompanied performance. Often, the latter is expressed as a cadenza at the conclusion of a piece or as an interlude; For Alto took that occasional, virtually ornamental phenomenon and made it the main--and exclusive--focus of an entire set of music. In doing so, the record raised questions that--here again is its radicalism--went to the root of the instrument's capabilities: what, when pushed to the extreme situation of an extended solo performance, could one do with the instrument's range of compass, of timbres, of expressive power? What, when reduced to a solo performance, is the relationship between the decisions made in the moment of an improvisation and the more enduring structures, both conceptual and technical, of the performer's musical vocabulary and concepts of musical architecture? For Alto modeled some of the answers and inspired others to find their own answers to those and similar questions.

In the 1970's, a diverse group of artists such as Roscoe Mitchell, Evan Parker, Lee Konitz, Kaoro Abe, Hamiet Bluiett and Steve Lacy issued solo recordings each of which reflected the artists' own, sometimes highly divergent ways of engaging the questions For Alto raised. Some of their performances were completely improvised, some departed from original compositions or concepts, others took the compositions of other artists as starting points.

At around the same time that jazz and creative musicians were exploring the implications of extended, unaccompanied saxophone performances, composers working in the tradition of the postwar classical avant-garde began creating works for solo saxophone as well. In fact, as early as 1956 Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi wrote "Tre pezzi" for tenor or soprano saxophone, a triptych of solo works that juxtapose long tones with more active lines in a collage-like manner. Although not improvised, the "Tre pezzi" works were rooted in Scelsi's own improvisational language. Japanese alto saxophonist/composer Ryo Noda in the early 1970's wrote several startlingly beautiful "Improvisations"--virtuoso pieces for solo alto saxophone that combined extended techniques with the traditional Japanese hirajoshi scale as well as phrasing and note-handling meant to emulate shakuhachi koto music. In 1981, composer Luciano Berio reworked his "Sequenza IX" for clarinet into "Sequenza IXb" for alto saxophone. As with the other compositions in the Sequenza series, "Sequenza IXb" was a virtuoso piece. Structurally, it was a modified serial work built up from two loosely handled pitch sets that were meant to imply harmonic movement and a sense of polyphony.

While these works were not improvised--although some were based on improvisations or inspired by improvisational music--they did address some of the technical and architectural challenges of solo saxophone performance, and did so in highly sophisticated ways. Berio's "Sequenza IXb," for example, explicitly confronted the problem of how to sustain a structurally cohesive musical logic over a given non-trivial period of time while relying on the resources of a single-line instrument; Berio's solution consisted of emulating the polyphonic sound of multiple lines through the measured deployment of differentiated pitch sets. Berio's architectural response to the problem of the saxophone's monophony was a de facto acknowledgement of the basic fact that the nature of the instrument is such that harmonic development of whatever sort--whether functional, modal, poly- or pantonal--will be implicit and thrown back onto the architectural structures that can be created by a single line moving forward in time. Inevitably, it is a diachronic rather than synchronic undertaking (even taking into account the use of multiphonics), a matter of implying the vertical dimension through the horizontal. It is an extremely demanding artistic situation in which to throw oneself as a performer, and one that can be expected to solicit a variety of creative responses.

Three contemporary artists who have worked consistently and creatively within the constraints of the solo saxophone performance have each come up with their own well-developed responses to the challenges inherent in the format. Two are European and one is an American, but what all three have in common is the working out of an effective musical vocabulary and syntax--an overall structure--capable of sustaining an unaccompanied, largely or wholly improvised performance on an essentially monophonic instrument.

Soprano saxophonist Gianni Mimmo of Pavia in Northern Italy is thoroughly conversant with the solo format, having become seriously engaged in solo performances since the early 2000's. One of the major inspirations for Mimmo's turn to solo performance was the example of Steve Lacy's solo work. Indeed, it was Lacy who moved Mimmo to focus exclusively on the soprano saxophone to begin with. Braxton, inevitably, was also an inspiration for Mimmo's solo work. Mimmo additionally looked to the classical avant-garde for structural cues, being interested in the way the Scelsi and Noda solo saxophone pieces handled space and in the way that Berio managed to construct a narrative arc out of the contrasts and balance of pitch elements in his own solo work. Beyond work written for solo saxophone, Mimmo looked to the lieder of Anton Webern, whose "Die Sonne" he performed and recorded in a version that drew out the harmonic and melodic implications while critically amplifying leaps in dynamics.

Mimmo's solo performances are expressive, but questions of formal relationships are never very far removed from the expressive imperative at hand. For him, the solo performance entails a very condensed and intense way of addressing the expressive possibilities of form, and he's often articulated his sense of musical form in spatial terms. Mimmo's approach can be thought of as based on a plastic sense of musical form; he's described imagining sound as consisting in the "possibility to position formal elements in space." Specifically when playing solo, Mimmo thinks not only spatially but in three dimensions; he's described himself as "sculpting" and as combining formal elements in a "complex, tri-dimensional structure." When he speaks of his performances as involving an interplay of "horizontalities and verticalities" he seems to go beyond using these terms as more or less standard, metaphors for melody and harmony and toward a vision in which melody and harmony take on an almost solid existence as the scaffolding on which a finished edifice can be built. (Not surprisingly, the visual arts are a great and continuing source of inspiration to Mimmo: he's built a solo program in which he improvises to seven paintings by artists as varied as Francis Bacon and Piero della Francesca.)

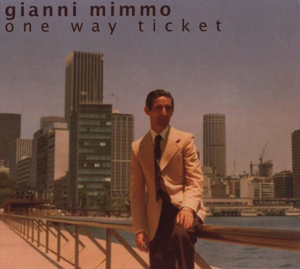

Mimmo's first solo release was One Way Ticket, a set of performances recorded in spring and summer of 2005. Although documenting performances from relatively early on in Mimmo's solo practice, One Way Ticket already demonstrated the range of his influences and inspirations. Bookended by brief recitations of work by poets T.S. Eliot and T. Scialoja, the recording includes Mimmo's interpretations of compositions by Monk, Mingus, Roscoe Mitchell, Steve Lacy as well as Webern's "Die Sonne." A decade later, Mimmo released a second set of solo performances as Further Considerations. Further Considerations contains compositions and improvisations inspired by painters Piet Mondrian and Mario Sironi as well as by the memory of Mimmo's late friend, the soprano saxophonist Gilles Laheurte. "Life," the piece dedicated to Laheurte, is the album's standout and an excellent demonstration of Mimmo's solo art.

Although fully improvised, "Life" is strongly imprinted by a sense of musical architecture. Throughout the performance, Mimmo builds medium- and long-period phrases out of compact figures--some of them as small as two-note pitch sets--that serve as structural motifs. These motifs remain recognizable even as he develops them through alterations of pitch relationships, internal structure and articulation. He may, for example, move them up and down registers, spin them out to changing terminal pitches, modify their tempo, or widen and narrow the intervals between their constituent pitches--all the while keeping the number of pitches and their rhythmic values constant. In this way Mimmo maintains thematic coherence while implying changes in modality, apparent key center and time. The resulting implications of harmonic change keep the improvisation moving forward in a way that pushes it into novel territory while leaving the underlying musical logic intact. "Life" is emotionally moving as well, helped along in this regard by Mimmo's calibrated use of extended techniques--multiphonics, voiced notes, harmonics--as a particularly sophisticated form of ornamentation that allows him to introduce surface disruptions into the refined, rounded tone that is the signature quality of his instrumental voice.

The motif-based architecture of "Life" gives it at times an accidentally quasi-modular flavor. By contrast, an explicit modularity is what lies behind the solo performances of alto saxophonist patrick brennan.

Detroit-born and New York-based, brennan--he spells his name with lower case letters--first began performing on solo saxophone when he was living in Europe in the 1990's. At that time, his solo performances consisted of the music of Monk, Ornette Coleman and similar composers; it wasn't until later that he began performing his own compositions solo.

In the 1970's, brennan began developing the idea of composing polyrhythmic work made up of overlapping melodic cells of varying time signatures and internal subdivisions. These cells would function as building blocks that, when orchestrated, would form the basis for collective improvisations by small to medium sized ensembles. He began to implement these ideas with his groups in the '70's and further developed them in the 1980's and 1990's, eventually coming up with the name "metagroove" to describe the music. In the late 1990's through the mid-2000's, he was performing metagroove pieces with his ensembles; during this period, he worked regularly with groups that consequently became accomplished at putting his ideas into practice. When one particularly adept group broke up in 2007, he suddenly found himself in the difficult position of being a composer without a means of realizing his compositions. His response to this predicament was to withdraw from public performance--in a 2015 interview on Blue Lake Public Radio, he described himself as essentially having gone on strike--and instead to work on honing his craft. It was at this time that he started adapting the metagroove compositions for solo saxophone--something he described in the same interview as having been "in a way a desperate move." Indeed, he calls his solo metagroove work "rōnin phasing"--named for Japan's desperate, dispossessed and wandering samurai, in which he found an apt analogy for his own situation as a composer without a band. Rōnin phasing may have begun in desperation, but it paid off in creative terms in no small part because of the challenges involved.

Because brennan's metagroove music is rooted in what he's described as a "multidimensional orchestral conception," the translation of those ideas into concrete sounds for the alto saxophone posed the specific challenge of how to realize an essentially polyphonic music on an unaccompanied, monophonic instrument. Metagroove was influenced by the elastic rhythms and the interaction of propulsion and stasis found in the music of Miles Davis' mid-1960's band with Tony Williams, in Detroit's CJQ and in Coltrane's 1960's music; thus, the basic compositional task for brennan was to orchestrate multiple blocks of polyrhythmic phrases in order to create forward motion as well as static vamps, as needed. With rōnin phasing, the question then became, how does one do all of that, and put it on a monophonic instrument? The solution brennan came up with involved staggering the initial beats of each rhythmic pattern and separating the pitch content of the modules in order to keep them perceptibly distinct (using changes in timbre to differentiate modules is something brennan considered but rejected as being less perceptually salient, and thus less musically effective than intervallic differentiation). Drawing on one of the techniques, he used in his solo work in Europe, he introduced transpositions into the modules, allowing him to alter the order of their pitch and rhythm components as desired, or to build phrases around a single pitch that would act as a kind of pivot or musical center of gravity.

"rough hue" is one of the metagroove compositions brennan adapted to solo saxophone. The piece comprises several modules or matrices containing basic melodic material in different time signatures; the melodies' phrasing is constructed of quarter notes, dotted quarter notes, and triplet quartet notes. These modules provide the core patterns that can be assembled into larger patterns through sequential ordering and interchange, and can be differentiated in performance with intervening silences and shifts in pitch and register.

A performance of "rough hue" broadcast on the 2015 Blue Lake Public Radio program is exemplary of metagroove translated into solo performance. The piece is relatively brief--it comes in under four minutes--but because of its brevity, it has a certain transparency that makes its structure all the more perceptible. It begins with a staccato burst of notes with a percussive flavor and develops through a series of rhythmically complex, harmonically pregnant moves, chief among them asymmetrically accented phrases and variations in dynamics as well as the displacement of the downbeat through leaps of register and the off-balance placement of quasi-leading tones (the invocation of leading tones to move the piece along shows the influence of the Bach cello suites on brennan's solo music). The rhythms are further elaborated with accelerating and decelerating tempos and pauses.

Roman multi-reedist Marco Colonna is one of the many improvising musicians profoundly interested in, and consequently engaged with, the expanded range of instrumental techniques and sounds opened up by the classical and jazz avant-gardes since the early postwar period. Like many other artists interested in these enhancements to the standard repertoire of instrumental gestures and timbres, Colonna has developed a musical aesthetic grounded in the self-aware leveraging of contemporary performance practices as the material correlate of a fundamentally expressive intent. In effect, Colonna has taken the raw materials of what for all practical purposes has become a kind of generic common practice for much adventurous new music and has refined them into something uniquely his, crafting with them a language that is both conceptually advanced and emotionally immediate at the same time.

Although Colonna's engagement with contemporary performance practices is largely in the service of the kind of expressive aesthetic ordinarily associated with music in the lineage of free jazz and creative music, it's important to recognize that Colonna is as much of the world of contemporary composed music as he is of the--often--complementary world of improvised music. His sensibility as a performer has been formed as much by works such as Berio's Sequenzas and Donatoni's "Soft" for solo bass clarinet as it has by the examples of Evan Parker and Rahsaan Roland Kirk. In fact, much of his activity in new music can be seen as moving farther along the routes laid out by Berio and Donatoni; new works for solo bass clarinet and contrabass clarinet have been dedicated to him by composers Giorgio Colombo Taccani, Dan Di Maggio, Sofia Mikaelyan and Shigaru Kan No. Colonna's identification with the classical experimental avant-garde goes beyond his work as an instrumentalist; he is also a composer, whose recent work has included writing solo pieces for piano in graphic notation.

As a performer, Colonna has participated in ensembles of various sizes and configurations, ranging from the large Setola di Maiale Unit, led by percussionist Stefano Giust, to the more intimate duo and trio settings that have found him collaborating with such musical partners as Mimmo, saxophonist Edoardo Marraffa, clarinetist Ben Goldberg, pianists Fabrizio Puglisi, Gianni Lenoci and Agusti Fernandez, percussionist Zlatko Kaucic and the Sardinian duo of double bassist Adriano Orrù and pianist Silvia Corda. Even so, it is his solo work that inevitably discloses the essence of his musical practice.

Colonna's solo performances, which he began doing in 1997, have been mostly on clarinet and bass clarinet--the latter of which has been the focus of increasing importance to him in recent years--but he has also done substantial work on unaccompanied baritone, alto and sopranino saxophones as well as on alto and contrabass clarinets and alto flute. He's documented his solo work in a prolific series of releases on which all of his instruments are well-covered, but it's his solo work on clarinet and bass clarinet that encapsulates in its purest form his way of forging a musical idiom that arises from his relationship to the instrument sounding by itself. He's quite willing to deconstruct the relationship between instrumentalist and instrument in quite literal ways, using extended techniques to defamiliarize the role each plays in relation to the other and thus to show how neither side can dominate the other but rather is bound to the other in mutual implication. He may, for example, remove parts of the instrument to foreground the fact that wind technique begins--and culminates in--the rush of breath through a tube, or parallel the sound of the instrument with the sound of his own voice, or improvise on the simple sound of a buzzing reed. What becomes exceedingly clear through his solo work is that for Colonna, musical practice is often about elucidating timbre as an independent variable on a footing equal to, if not at times greater than, pitch or harmony. In fact, of the three artists here, he is perhaps the one who most fully integrates timbre as an element in and of itself--as often as not in the guise of unpitched sound--into his performances.

A perfect example of Colonna's foregrounding of timbre is to be found in "Guernica in fondo al mare," a solo performance on baritone saxophone that appears on Colonna's 2017 release of the same name. In addition to the title track, the album includes solo performances for bass clarinet, Bb clarinet and alto flute. Some of these are improvised, some are Stravinsky compositions that Colonna arranged, and one is Colonna's interpretation of Hawkins' "Picasso" on bass clarinet.

"Guernica al fondo" is a forceful seven-minute long performance that takes a particularly reductive stance toward pitch. In fact, throughout the piece, Colonna reduces pitch movement to a minimal, oscillating relationship between two tones, a relationship that he maintains at times more broadly and loosely than at others, and that he occasionally shifts up and down the instrument's compass. Essentially though, changes in pitch are incidental; what really provides the basic material for the piece is timbre, which Colonna varies in a number of creative ways. Starting off with a breathy attack shading over into a whistle, Colonna pushes his sound into harsher territory, giving the tone a serrated edge honed with a shriek. He easily shifts the tone from caustic to muted, overblows, splits notes, layers in multiphonics, breaks the oscillating pitch pattern with low-register grunts, and blurs the boundary between pitches with a guttural buzz. Timbral variation clearly is the motor driving the development of the piece, with changes in dynamics playing a supplementary, albeit still important, role.

Three artists, three different paths through the field opened up and partly mapped by For Alto, "Tre pezzi," "Sequenza IXb," and Noda's "Improvisations." Different but complementary, it must be said. For while Mimmo, brennan and Colonna have come to take three distinctive paths on their way to creating structurally coherent, expressively effective solo improvisations for the monophonic saxophone, their three routes converge on that common point where an artist's practice is successfully defined as much by clarity of purpose as by the constraints afforded by the instrument and the precedents of past practice. Whether by melodic theme and variations, modular polyrhythms or timbral contrast and likeness, all three have managed to base their solo performances on a sometimes intuitive, sometimes self-consciously articulated, architectural scheme to tie together disparate musical elements and to keep them moving forward according to a cohesive internal logic.

Three artists, three different paths--paths through a field expansive enough to leave room for many others.

And see more about: