Susumu Hirasawa

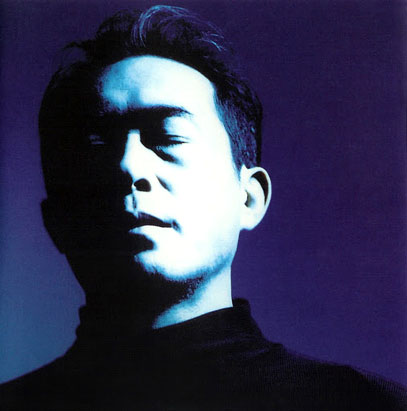

Lost in thought: Technique of Relief, 1998

Dreaming Machine

by Nick Reed

(June 2013)

October 22nd, 2007. I'm in Milwaukee to see a band called Polysics, a hyper intense Japanese New Wave group that somehow got put on a bill with alt-rock bands like Hellogoodbye and Say Anything. At 21, I already feel like the old guy in this packed crowd, and am one of the twenty or so people here who actually came to see this crazy opening act. Many of them are wearing anime shirts; I'm maybe the only one who got into the band thanks to their unabashed Devo obsession. Before they come on, there is some house music to warm up the crowd. It's mostly ‘80's stuff, including some crowd pleasers like "Take on Me" (which most of the audience, very few of whom were even alive when it was released, shriek at the top of their lungs). Also included: some Devo, New Order, and the Yellow Magic Orchestra song "Cosmic Surfin'." This playlist was clearly compiled by Polysics themselves. Then I hear one I don't recognize - it's quick, full of nervous energy, with manic vocals, a ringing synth line, and a real catchy solo part. Whoever they were, Polysics were clearly big fans of them; it sounded like a lost Polysics tune. After the show I approach Hiro (a.k.a. POLY-1, the lead singer of the group) to ask who that band was. He writes their name down on a slip of paper and hands it to me.

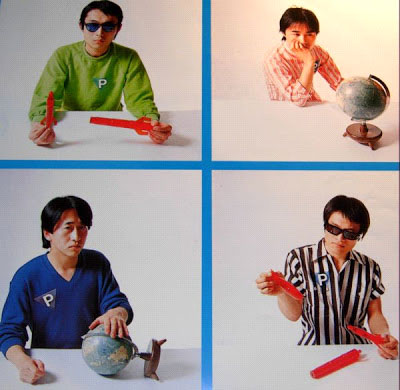

P-Model; original lineup circa 1979

That was the first time I ever heard P-Model. The now-defunct Mutant Sounds had put out their first two albums - 1979's In a Model Room and 1980's Landsale. I didn't have to wait long to hear the tune I was looking for - it was called "Art Mania" and it was the very first song on their first album. And it was just as perfect as I had remembered it being. On the surface, this was a lot like Devo, or maybe White Music era-XTC; very clean and energetic, lots of stop-n-go bits, some call-and-response, and a singer that sounded possessed; always out of breath, alternating between singing and just yelping out the words. It was the kind of music that replicates a coffee buzz, as it’s nearly impossible to hold still while it's playing. There were songs that switched time signatures on a dime, and bass lines that were a lot more complicated than what you'd normally associate with New Wave. Even though most Japanese groups at the time sung in English, almost everything was in Japanese outside of "Sophisticated," which stretches the title to six syllables and ends on the line "Sophisticated, the foreign language song." The chorus of the brilliant, stupidly catchy "Kameari Pop" is just "hey you, this song is called Kameari Pop." This was technopop, alright, but with a sense of complexity and irony. Indeed, P-Model were once a progressive rock band called Mandrake, and the song "The Great Brain," which constantly switches between 5/4 and 7/4, was once part of a ten minute prog epic. These guys sounded raw, but they had skill.

At the time I had no idea how vast the discography of P-Model, and in particular their leader, Susumu Hirasawa, actually was. I was obsessed with In a Model Room (a little less so with Landsale), but I thought they were just one of the many cool, quirky groups to come out of Japan in the late ‘70's, like Ippu-Do or the Plastics. I had no idea that Hirasawa had only recently become somewhat famous in America thanks to his soundtrack for Satoshi Kon's rather surreal film Paprika, nor of the nearly religious following that he still has today. I had no idea that the two albums I had made up merely the first disc of P-Model's 16-CD Ashu-On set (Hirasawa released another 16-disc box last year, covering his solo work up to the year 2000, and he's done enough since to justify another one). These groups tend to burn out fast. When I heard 1982's Perspective, it felt like they had already jumped off the deep end, never to return. One, because it has perhaps the loudest gated drum sound I have ever heard on an album. This was not the sound of someone falling in love with an effect that did not date well; this was a conscious decision made to disorient the listener. Two, the songs are absolutely nuts; "Heaven" is based on a triumphant synth riff and a cut up bass line haphazardly looped around (often out of sync) while Hirasawa loudly warbles off-key. And this was the single?! Where were they going with this?

Hirasawa phones a friend, 1990

As it turns out, Susumu Hirasawa and P-Model did not burn out. Perhaps aided by a rotating cast of auxiliary members, they were always trying new things in an attempt to find themselves as a band. They brought in MIDI controls, used tape loops, wrote wonky bass lines that would repeat through the whole song, experimented with marching rhythms, mixed digital and acoustic sounds, chopped up vocals and used them as hooks, or multi-tracked them to sound like choirs. 1986's One Pattern was the group's last album before they split (or "froze", as Hirasawa would call it), by which point it was hard to tell exactly what P-Model was anymore. Hirasawa released a trio of solo albums that were all over the map, painting the man as nothing short of a lunatic (the screenshot above is a shot from the mile-a-minute video of "Sekai Turbine," one of Hirasawa’s many music videos that abuse early CGI). While it's tough for us English speakers to know what any of this was about (apparently even native Japanese speakers struggle with it), he does at least attempt to keep us informed. 1991's Virtual Rabbit was, in his words, about the "world of dreams which has been lost due to the encroachment of science." As far as lofty concepts for Hirasawa solo albums go, this may not even crack the top ten. But there is something to this idea.

Perhaps this was Hirasawa's main goal - the intersection of a surreal dreamlike world with a precise, scientific sense of advancement. In 1992, Hirasawa "de-frosted" P-Model, and they came back more focused than ever. Rather than continue in the direction they were going, they went all the way back to In a Model Room. Nearly every aspect of their old sound was chucked - in lieu of their complex bass lines, Hirasawa now employed a sequencer to create rhythms that sounded like Tangerine Dream gone technopop. The synths have gone all digital, often playing melodies that would seem impossible for a human to play (and in many cases are), with sweeping waves of sound and blippy noises in every corner. The guitar is not really present, outside of some rather wild solos (dubbed "destroy guitar" by Hirasawa), but it’s still there when needed. Their first album post-reformation was simply called P-Model, and the name is rather apt. This is not a case of a band reuniting and trying to recapture past glories, or even a band that wanted to act as though they hadn't split. This is a band that simply wanted to start over. The spirit of 1992 is all over this thing, but not in a way that makes it unlistenable today - the songs are hooky, brief, and sometimes gorgeous. The same nervous energy that punctuated In a Model Room is all over the place on P-Model. Just to drive the point home further, there is an unlisted 'bonus track' called "No Room," a de facto remake of "Art Mania", with that same perfect solo.

Such is the nature of Hirasawa. Many artists speak of how they feel they are improving all the time, but Hirasawa really puts in the work. Every album brings at least one new trick to the table, and his voice and technique seems to be constantly improving. If you see Hirasawa live, chances are he will play little outside of his last few years of work, and the fans do not seem to mind this at all. Part of this is because he's constantly inventing new technology for the job - not only is he a legend in the Amiga community (he even wrote the boot jingle), but his live shows feature instruments that Hirasawa has himself built from scratch. If nothing else, the music is certainly getting bigger - I recall hearing 1995's Sim City for the first time while driving on the highway and feeling as though the sound was coming from miles away. The word "epic" is perhaps the most misused adjective in the English language right now, but there really is no other way to describe it; this stuff has the power of an entire symphony, but every instrument and detail is controlled by just one man. The recordings are so nuanced and layered that you wonder if he ever left the studio. This is music that makes you lose yourself; when he's really on, you almost have to remember to breathe. The big moments can be such a rush that they practically force you to listen on repeat, and the songs are detailed and complex enough to justify hearing them over and over. Elements in the foreground play off elements in the background in ways that take a dozen or more listens to reveal. And yet, it is clearly the work of a guy who was been writing goofball technopop since 1979 - the sequencers are still there, the songs are still catchy, and there's still an unhinged quality to everything he does. The chopped up vocals and ever-present marching rhythms that show up in so many different forms are things he's been doing since 1985. As John Peel famously said about The Fall, "always different, always the same". Hirasawa embodies that slogan, but he takes it one step further - to date, he's released five "remake" albums that feature old songs done in an updated style. Soundtrack albums often share a lot of similarities with concurrent solo albums; half of his score to Millenium Actress is essentially an ambient mix of 2000's Philosopher's Propeller (ditto Paprika and 2006's Byakkoya - White Tiger Field). There is often a lot to explore in any given composition.

During an interview that Hirasawa gave in 1994, he described how he modified the Amiga "Super Jam" program (which can generate unique chord sequences in a variety of styles) to spit out a song "Hirasawa-style" by feeding it a bunch of his existing compositions. I have no idea if this is true or not; hard facts on Hirasawa are hard to come by in English, but it does not seem so farfetched from a man who built his own solar-powered instruments (he famously did a show in the rain in which he had to constantly spin a wheel as a means of generating power), modified a laser harp to trigger samples of his own voice, and toured with a Tesla coil that would randomly generate sound. The song that it supposedly came up with was "Take the Wheel," a track from Aurora that Hirasawa later re-worked into "Forces," the theme from Berserk. This is not exactly his greatest composition, but it may be his most famous one. Even if he never used the program again, the fact that he ever did represents a perfect ideal of what Hirasawa's work is about. After all, Hirasawa is much like a machine himself. New material still comes like clockwork - perhaps not at the feverish pace it did in the ‘90's, but there is still a new one every three years. This, in addition to his soundtrack work, his remake projects (he spent most of 2010 giving his solo and P-Model songs new orchestral arrangements), or one-offs like 2004's excellent Vistoron, released as Kaku P-Model (Kaku means "core" - it's really just another solo album), or 2005's Ice-9, an album of Oldfield-like guitar instrumentals. His work evolves naturally - every album tends to be a combination of 80% old and 20% new, and few Hirasawa albums are markedly different from their predecessor. But that 20% adds up over time. It is rather jarring to watch clips of say, "Kameari Pop" back-to-back with 1998's "Gardener King"; how could this be the same person? Even Andy Partridge's transformation from jerky New Wave dude to the second coming of Paul McCartney wasn't this dramatic. But it is a logical evolution; every album has elements that foreshadow the future, even in the early stages - In a Model Room's "Art Blind" and Landsale's "Ohayo" were both hints at what was to come on later albums. Elements that seem experimental later become mainstays.

This is the promise of a good debut album. We want artists to grow, but without losing that initial spark, whatever it was that made us like them in the first place. We want to know that should we fall in love with a song, there will be others that we may love as well. We want the elements that impress us at first to feel effortless as the artist gains more experience. We want each new album to be a potential goldmine. We want them to try new things, but to correct their missteps along the way. And Hirasawa hasn't been immune to that; some albums feel a bit disjointed, and his early adoption of digitalization resulted in some odd production choices (in particular, on his first three solo albums). Perhaps he does repeat himself a bit too much. And yet, the man has yet to make an album that feels inessential - even One Pattern (Hirasawa's own pick for worst P-Model album, due to too much record label interference) has several great cuts. In other words, yes, you do need the 16-disc boxset. The 'side' releases (for example, the more experimental albums released under the name SHUN, or his early soundtracks for Detonator Orgun) aren't held to the same high standards as the "main" albums, but there are gems everywhere. The Ashu-On boxset is full of clues as to where his work would go, if you're paying attention.

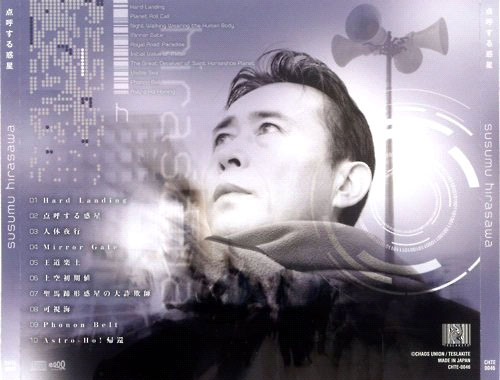

Back cover: Planet Roll Call, 2009.

On April 2nd, 2014, Susumu Hirasawa will turn 60 years old. This is a rather staggering fact. Many artists peak in their 20's. Most of the giants of the 1970's were in major decline by the time they hit 40. When Susumu Hirasawa was 40, he had just reformed P-Model and began a series of incredible solo albums, starting with 1994's Aurora; perhaps the first album that really resembles the Hirasawa we know today. This is a series that is still ongoing; his latest, 2012's Secret of the Flowers of Phenomenon, does not disappoint. When will age finally catch up with him? His voice has not changed at all; even his outward appearance remains oddly static. His skills on the guitar seem to only get better - "Luuktung or Daai" (perhaps Hirasawa's only song written solely as a crowd-pleaser) has a twisted, cut up guitar bit reminiscent of the solo in Cardiacs' "Fiery Gun Hand" and it's the kind of thing you'd swear was digitally manipulated, until you see him do it live. There is something about this man that feels inhuman; the modified "Super Jam" program that generated "Take the Wheel" doesn't seem terribly different from what goes on in Hirasawa's brain. He cannot help sound more like himself with every release; he only goes deeper and deeper into his own rabbit hole. What influences the man? He clearly derives a lot from Asian culture, an influence that shows up in many different guises. There is a touch of Vangelis in his work - he has sampled bits of 666 here and there, and "Ageal Song" from the Lost Legend soundtrack is markedly similar to "A Song" from Earth. Perhaps there is some Floyd here as well (P-Model covered "Bike" in 1983). But his primary influence seems to be himself. If you like one Hirasawa album, chances are you will like all of them.

Hirasawa's turning point as an artist was 1992's P-Model, a concept album about the life inside of computers. One of the songs has a chorus urging the listener to "wire yourself," a mantra for Hirasawa's own life. By 1995, P-Model had hired the services of a "virtual drummer" that could be programmed to do things a real drummer could not. His early solo performances were full of guest performers (including Jun Togawa, for whom Hirasawa has written several songs for). It is quite obvious which ones they are), but when P-Model disbanded for good, Hirasawa soon realized that he did not have to work with anyone else. His live shows are one-man performances, though there is the feeling that the real star is the dizzying array of cutting-edge technology on stage with him at all times. You do not see much emotion out of Hirasawa; he is a slave to the audience and the machines, and it seems as though he is always questioning what his role in all this really is. Is his goal to one day have the machines write the music for him too? Are there still corners of Hirasawa's brain to explore? There is still time; a 66-year old David Bowie just released one of the most hyped albums of the year, while Scott Walker's newest garnered massive critical praise and is considered cutting edge, and he turned 70 a month after its release. Both of these albums were considered "comebacks" after long periods of inactivity, something which Hirasawa has yet to take. The question is whether or not he ever will.

Epilogue:

If you're interested in the work of Hirasawa but don't know where to start, I've listed 12 songs below that should at least function as a short guide to his evolution throughout the years. All of these songs should be readily available on YouTube. If there's anything you like, the corresponding albums are all worth checking out (the ones with stars are as P-Model). While it's definitely fascinating to try to listen to this stuff in order, that is a massive undertaking. If I had to recommend one album as a jump off point it would probably be 1995's Sim City.

1. "Art Mania". In a Model Room, 1979.*

2. "Personal Pulse". Another Game, 1984.*

3. "Dance Subomp". Karkador, 1985.*

4. "Bandiria Travellers". Virtual Rabbit, 1991.

5. "Chevron". Big Body, 1993.*

6. "Snow Blind". Aurora, 1994.

7. "Ashura Clock". Ashura Clock single, 1997.*

8. "The Man From Narcissus Space". Technique of Relief, 1998.

9. "Logic Air Force". P-Model or Die, 1999.*

10. "Opus". Philosopher's Propeller, 2000.

11. "Switched-On Lotus". Switched-On Lotus, 2005.

12. "Phonon Belt". Planet Roll Call, 2009.